Review: Sixty Million Frenchmen Can’t Be Wrong

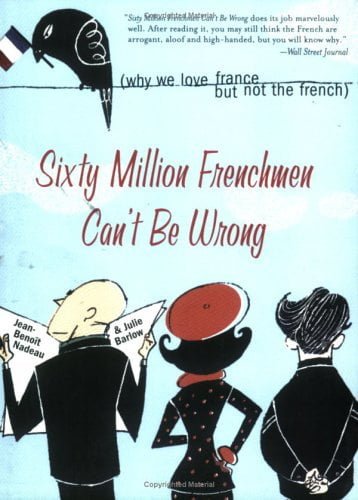

Sixty Million Frenchmen Can’t Be Wrong: Why We Love France but Not the French was written by journalists Jean-Benoit Nadeau and Julie Barlow. As Nadeau is a French-speaking Quebecker and Barlow is an English-speaking Canadian, and they spent two years living in France, they provide great insights into the cultural and economic differences between America, Canada and France.

Its listing as Expatica‘s number one book on figuring out the French prompted me to read it. I doubt I would have read it without it, because, well, I do like the French. Thankfully, in this case, the title is misleading. Nadeau and Barlow explain the title in the introduction:

‘The title, borrowed from a Cole Porter musical – Fifty Million Frenchmen Can’t Be Wrong – is not meant to be taken literally. It merely reflects our sympathy, and our goal to challenge assumptions about France. It is easier to pass judgement on the French, but much harder to examine them in their own terms and their own turf – hence the title.’

They point out that travellers to Africa or Asia expect, and even hope for, a certain level of cultural dissonance. A significant part of overseas travel is discovering how different people live and reflecting on some of your own assumptions. However, when people travel to France, they often don’t think this way. They don’t appreciate that the French has a different history, culture and intuitions; and tend to talk about France in terms of ‘have nots’ compared to America (‘e.g.: French waiters don’t smile’, ‘The French have no work ethic’.)

Sixty Million Frenchmen Can’t Be Wrong explains French behaviour in the context of its recent history, including World War II, the Algerian War and the beginnings of the European Union. It also explores more longstanding cultural traits, for example I had never considered the impact of France’s Catholic history on the national psyche, including on its people’s reverence for grandeur and authority.

Other chapters explore the French insistence on precision in language and expression (including in revered arguments about philosophy and politics), their sense of privacy, integration and the effects of immigration.

On privacy, Nadeau and Barlow explain that in France eating is public. Private spaces like homes, particularly bedrooms, are fiercely defended. Even a shop is a private space, more like entering someones home than popping into a Costco. Asking what someone does for work or anything about money are considered breaches of privacy.

The chapter on Muslim integration in France is particularly interesting. It explains that France has the largest Muslim population in Europe. The recent changes banning overtly religious symbols, such as crucifixes and head scarfs is explained, in part, as an extension of the French policy of complete integration/assimilation (including secularism). This was first exercised against regional differences and then immigrants. For example, the French government cannot legally ask about religion, native language or ethnic origin on the census.

But the policy of assimilation does not work well with the Muslim community, because they might look different and have distinctive names, and racism is widespread. Also, this community is actually shaping the national identity, as Nadeau and Barlow explain:

‘Beur [slang for the child of Arab immigrants] culture is different, though, partly because of the sheer demographic weight of the North African immigrants. Beurs are provoking a grassroots cultural shift powerful enough to redefine mainstream French culture altogether.’

Nadeau and Barlow’s discussion about the differences between French and north American culture is the book’s strength. When they discussed politics, I questioned their authority and the logic of conclusions they made (even if I agree with the sentiment). Furthermore, Sixty Million Frenchmen Can’t Be Wrong is nearly ten years old, so the ‘current’ social and political issues are not so current.

Overall, it is well researched and densely packed with facts and figures. Sixty Million Frenchmen Can’t Be Wrong would be a great handbook for American, Canadian, Australian and English tourists and expats, to make sense of French people and institutions.