“Je me souviens”— à la Elisabeth #15 – #18

This series began here “Je me souviens” #1-#7

And here you’ll find “Je me souviens” #8-#14

And “Je me souviens” #15-#18 (this one)

Then you’ll discover #19-#21 here

I am starting something about which I have been thinking for quite a while, a little mimicry of “Je me souviens” (“I remember”) by Georges Perec.

Every day I will prepare a “Je me souviens” post – both in French and in English and present them here for you frequently… please feel free to add your own memories in the comments below.

In terms of how MyFrenchLife members may benefit from this new series, it may help you understand cultural events and societal issues in France in the recent past (my lifetime) as I grew up in the north of France. These posts can also be used to help with your French language practice. Amusez-vous.

Context

For those who are not familiar with George Parec and his book/s this might help provide context:

“Impossible book to put down. In fact, I’m going to read it again. Kind of based on Joe Brainard’s famous and great “I Remember’ but different in that Perec didn’t read that book, but he heard about it from his friend the writer Harry Mathews. While Brainard’s book is more personal and deals with his own observations, Perec’s take on “I Remember” is more of the collective memory of the French from a certain time, mostly from the post-war years. So what he remembers here are a lot of French figures from the cinema, music and pop cultural world of Paris 1950s to the 60s – and I think beyond. My favorite, of course, is “I remember that Boris Vian died while coming out of a showing of a film adapted from his book ‘I Spit on Your Graves'”

by ‘Tosh’ from Goodreads, where you can read more…

Navigation

How to Navigate these “Je me souviens” articles? Each of these articles is updated daily and published weekly, so that you get 7 posts all at once – total immersion: French culture and French language immersion all in one.

— If you haven’t seen this article before, then start at the very bottom of this page.

— The most recent posts are found immediately below this comment.

Je me souviens #18: un magasin de poissonnerie et volailles à La Madeleine

Je me souviens que, pendant un certain temps vers le milieu des années soixante, mon frère et moi passions une bonne partie de notre jeudi après-midi à faire des livraisons de poisson à des clients de mes parents.

A l’époque, le jeudi était un jour de congé pour les écoliers en France (en 1972, ce jour de congé est devenu le mercredi.)

Mes parents avaient un magasin de poissonnerie et volailles à La Madeleine, dans la banlieue de Lille. Ce magasin était fermé le lundi, ils y vendaient de la volaille le mardi et le mercredi, du poisson le jeudi et le vendredi, et de la volaille le samedi et le dimanche matin (Ils avaient une rôtisserie dans leur boutique, et la vente de poulets rôtis était excellente le dimanche matin.)

Il semble un peu absurde qu’un même magasin puisse vendre deux types de produits frais aussi différents, mais je peux vous garantir que ce que vendait ma mère était toujours frais et d’excellente qualité et que son magasin était d’une propreté incroyable et qu’elle y respectait toutes les règles sanitaires et d’hygiène alimentaire possibles et imaginables.

Jusque vers la fin de l’année 1966, l’Eglise catholique exigeait encore de ses fidèles qu’ils s’abstiennent de viande le vendredi. La plupart des catholiques mangeaient donc souvent du poisson ce jour-là, et le commerce de mes parents était très fréquenté le jeudi et le vendredi. Je sais que ce fut pratiquement un désastre pour eux lorsque l’Eglise catholique abolit cette obligation de “faire maigre” le vendredi – sauf pendant le Carême – et que ma mère eut bien du mal à avaler cette pilulle plutôt amère. Cela, avec la concurrence croissante des supermarchés, devait la pousser à commencer à vendre aussi des fruits et légumes vers 1967, et de finalement vendre son commerce en 1968.

Mon frère et moi avions tous deux un vélo. Le mien était un vieux vélo que mon père avait fait remettre en état et repeindre (il était bleu pale) pour moi; celui de mon frère avait été acheté neuf, et il était orange, je pense. Un soir, j’avais oublié de rentrer mon vélo et de le mettre dans notre cour et il avait disparu le lendemain matin. Je ne l’ai jamais revu….

Nous partions donc, chacun de notre côté, et notre rayon de livraisons était d’environ cinq kilomètres, mais nous devions bien en parcourir de huit à dix, sinon plus, dans l’après-midi. Nous allions au domicile des clients qui avaient commandé leur poisson du vendredi, sonnions à leur porte et leur donnions leur poisson, bien emballé et étiquetté par ma mère. Je ne pense pas que nous étions responsables de collecter de l’argent, mais il est possible que nous le faisions. Je sais que j’aimais assez bien faire ces livraisons. Nos parents ne nous payaient pas pour ce service, mais cela me donnait un certain sens des responsabilités.

Photos:

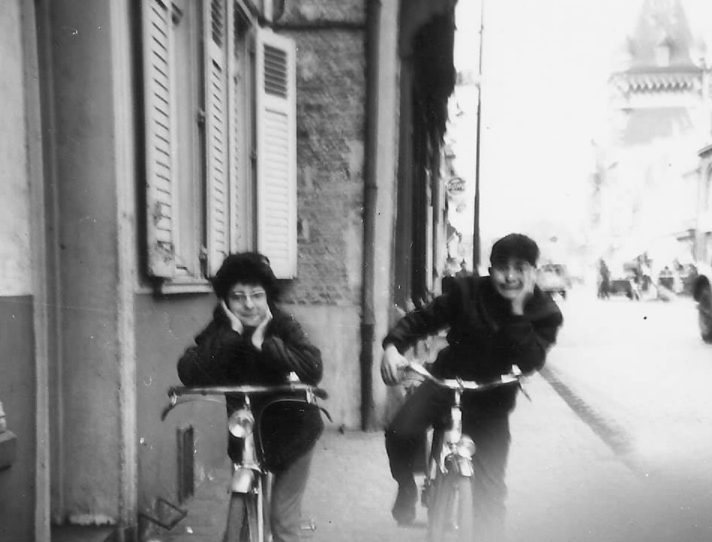

– La poissonnerie-volailles de mes parents, avec le véso de mon frère (à droite) et le mien (à gauche.)

– Mon frère et moi, probablement prêta à partir faire nos livraisons. Photos prises en septembre 1965.

Translation:

I remember that, for some time in the mid-1960s, my brother and I would spend a good deal of our Thursday afternoons delivering fish to my parents’ customers. At the time, Thursday was a day when French children had no school (in 1972, that day off was switched to Wednesday.) My parents owned a fish and poultry shop in La Madeleine, a suburb of Lille. This shop was closed on Monday, they would sell poultry on Tuesdays and Wednesdays, fish on Thursdays and Fridays, and poultry on Saturdays and on Sunday mornings (they had a rotisserie in the shop, and sold a lot of roasted chickens on Sunday mornings.) It seems a bit absurd that, in that one shop, they could sell two types of fresh food items as different as fish and poultry, but I can guarantee that what my mother sold was always very fresh and of top-notch quality, and that her shop was incredibly clean, and that she respected every single rule of food sanitation and hygiene. Until the end of the year 1966, the Catholic Church required practicing Catholics to abstain from meat on Fridays. Most of them would often eat fish on that day, and my parents’ shop was very busy on Thursdays and Fridays. I know that it was a quasi-disaster for them when the Catholic Church did away with that “lean Friday” obligation – except during Lent – and that my mother had a very tough time swallowing that bitter pill. That, compounded with the increasing competition of supermarkets, led her to start selling also fruits and vegetables around 1967 and to end up selling her shop in 1968. My brother and I each had a bike. Mine was an old one that my father had refurbished and repainted (it was light blue) for me; my brother’s had been bought new, and it was orange, I think. One night, I forgot to bring my bike in and to put it in our backyard, and it had vanished by the next morning. I never saw it again. We would leave, each going our own way, and would cover a four-kilometer radius territory, maybe for a total of eight to ten kilometers, maybe more, in the afternoon. We went to the houses of customers who had ordered their Friday fish, would ring their doorbell, and give them their fish, nicely packaged and labelled by my mother. I do not think that we had to collect any money, but maybe we did. I know that I was quite fond of making those deliveries. Our parents would not pay us for this job, but it gave me some sense of responsibility.

Photos:

– My parents’ fish and poultry shop, with my brother’s bike (on the right), and mine (on the left.)

– My brother and me, most likely ready to leave to make our fish deliveries

Je me souviens #17: “Quand J’entends le mot culture, je sors mon transistor”

Je me souviens que, quand mon frère et moi étions adolescents, entre 1965 et 1968, je pense, nous écoutions assidûment, tous les dimanches, sur Radio-Luxembourg (par la suite RTL), l’émission satirique de Jean Yanne, “Quand J’entends le mot culture, je sors mon transistor.”

*Nous avions alors un gros magnétophone que ma mère avait acheté d’occasion à l’un de ses fournisseurs, et nous prenions bien soin d’enregistrer ce programme. Puis nous passions pas mal de temps à improviser des sketchs à la Jean Yanne que nous enregistrions sur notre magnétophone.

Je n’ai absolument rien trouvé sur l’internet sur cette émission de radio, sauf une brève allusion qui y est faite sur le blog “Radio Fañch” (Lundi 15 février 2021, “Quand j’entends le mot culture, je sors mon transistor.”) Je me souviens que ce programme était hilarant, irrévérencieux et consistait en une série de sketchs partiellement improvisés mais remarquablement construits.

Le seul sketch dont je me souvienne vraiment et qui figurait au programme chaque semaine mettait en scène Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet, l’Aigle De Meaux, et son bedeau Marcel.

– Jean Yanne tenait le rôle de Bossuet [Bossuet, 1627-1704, était l’évêque de Meaux, près de Paris;

– il est célèbre pour ses sermons et ses oraisons funèbres] et

– Daniel Prévost celui de Marcel.

Avec son accent de Titi parisien, Jean Yanne faisait un pastiche de sermon – genre oratoire auquel Bossuet doit sa célébrité – parfois interrompu par Marcel, et qui se terminait toujours par un mauvais jeu de mots (je me souviens de celui-ci, “Monseigneur, vous prêchez dans le dessert.”)

Jean Yanne eut la distinction notoire d’être (avec Coluche) l’humoriste français le plus souvent licencié – il fut mis à la porte par Radio-Luxembourg en 1969, puis par Europe 1, et enfin par France-Inter.

Son sketch de 1965 avec Jacques Martin dans l’émission de télévision “Un égale trois,” intitulé “Premier tour d’Europe cycliste,” dans lequel Napoléon et ses généraux sont des coureurs cyclistes que viennent coiffer sur le Poteau Wellington et Blücher à Waterloo déplut tellement au ministère de l’information que cette émission fut suprimée par l’ORTF après seulement cinq épisodes. C’était aussi un individu aux talents multiples: Jean Yanne écrivit des chansons (les paroles et, parfois aussi, la musique) et eut une carrière prolifique au cinéma – en tant qu’excellent acteur, surtout, mais aussi comme producteur et réalisateur de films, souvent des satires caustiques et déjantées de la radio et de la télévision, de la politique et du monde du spectacle.

Il devait disparaître prématurément, victime d’une crise cardiaque en mai 2003, quelques mois avant ses 70 ans. J’en fus profondément attristée.

Son ami et comparse, Olivier de Kersauson, devait dire de lui qu’il avait:

“Un colossal sens de la déconnade dans ce qu’elle peut avoir de jubilatoire et de gentil. C’était pas se moquer des autres, c’était se moquer de soi, de ce qu’est la vie, de ce que sont les gens, de tout ce qui les entoure.”

Je pense qu’avec Jean Yanne, mon frère et moi firent connaissance avec un sens de l’humour hors du commun et d’une philosophie de l’existence et du monde à la fois désabusée et critique, alimentée par un sens de l’observation époustouflant.

* Je ne savais pas que cette phrase était une parodie de l’aphorisme célèbre du dramaturge nazi Hanns Johst, “quand j’entends le mot culture, je sors mon revolver.”

Video

– Jean Yanne et Daniel Prévost, sketch “Le Manifestant professionnel.” 1970.

Translate:

I remember that, when my brother and I were teenagers, between 1965 and 1968, I believe, we listened faithfully, every Sunday on Radio-Luxembourg (which became RTL later on), to the satirical program created by Jean Yanne, a famous French humorist, which was titled “When I hear the word culture, I pull out my transistor radio.”

*At the time, we had a big reel-to-reel tape recorder that my mother had bought second-hand from one of her suppliers, and we would make sure to record this program. Then, we would spend quite a bit of time improvising skits inspired by Jean Yanne’s, that we taped on our tape recorder. I found practically nothing on the internet on this radio program, except for a brief mention made of it in a post on the blog “Radio Fañch” (Monday, February 15, 2021, titled “Quand j’entends le mot culture, je sors mon transistor.) I remember that this show was hilarious, irreverent, and consisted of a series of skits that were partially improvised but remarkably articulated. The only skit that I remember and that was on the program each week featured Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet, the Eagle of Meaux [Bossuet, 1627-1704, was the catholic bishop of Meaux, near Paris; he is famous for his sermons and funeral eulogies] and his acolyte, Marcel [a fictitious character.] Jean Yanne played the role of Bossuet, and Daniel Prévost the role of Marcel. With his working-class Parisian accent, Jean Yanne would give a mock sermon, sometimes interrupted by Marcel, which would always end by a mad pun (I remember this one: “Your Grace, you are preaching in the desert.”)Jean Yanne earned the notorious distinction of being (with the comedian Coluche) the French humorist to be most often fired – he was let go by Radio-Luxembourg in 1969, then by Europe 1, and finally by France-Inter. His 1965 skit with Jacques Martin [another famous French comedian] in the TV show “Un égale trois” [“One equals three”], titled “Premier tour d’Europe cycliste” [“The First European Bicycle Tour”], in which Napoléon and his generals are bike racers whom Wellington and Blücher overtake in a dramatic finish at Waterloo, angered ministry of information officials so much that this show was canceled by the ORTF (France’s government-owned TV station – the only one in existence in France at the time) after only five episodes. He was also a multi-talented individual: Jean Yanne wrote songs (lyrics and, sometimes, also the music) and had a prolific film career – as an excellent actor, mostly, but also as a movie producer and director. His films were often caustic and off-the-wall satires on radio and television, politics and show-business. He died prematurely, of a heart attack in May 2003, a few months before his 70th birthday. I was very much saddened by his death.

His friend and occasional collaborator, Olivier de Kersauson, said about him that he had “an enormous sense of joking around, in a way that was both exhilarating and nice. It was not making fun of others, it was making fun of oneself, of what life and people, and everything around them was all about.” I think that, with Jean Yanne, my brother and I became acquainted with an unusual sense of humor and philosophy of existence and of the world at the same time cynical and critical, and fueled by a mind-blowing sense of observation.

* I had no clue that this sentence was a parody of the famous aphorism by the nazi playwright Hanns Johst, “when I hear the word culture, I pull out my handgun.”

Video

– Jean Yanne and Daniel Prévost, “Le Manifestant professionnel” [“The Professional Demonstrator.”]

Je me souviens #16: “Grande Guerre,” 1914-18:

Je me souviens des anciens combattants de la “Grande Guerre,” celle de 1914-18, et des histoires que j’entendais autour de moi sur la Première Mondiale quand j’étais enfant.

Comme je suis née en 1952, quand j’avais entre 8 et 18 ans, bon nombre de personnes du nord de la France qui avaient vécu les quatre années de cette guerre étaient encore vivantes.

Pour moi donc, le terme “ancien combattant,” à l’époque désignait ceux qui avaient combattu dans les tranchées de 14-18, et pas vraiment les vétérans français de la deuxième guerre mondiale. Mon idée de ces hommes étaient qu’ils avaient tous l’âge de mon grand-père maternel qui, lui, n’avait pas servi sous les drapeaux en 14-18 (Il avait fait son service militaire bien avant la guerre). Ils étaient donc vieux, et parfois “mutilés de guerre” – il leur manquait parfois une jambe ou un bras, on les voyait défiler le 11 novembre.

Je me souviens plus particulièrement de Monsieur Cambier. Sa femme et lui étaient les propriétaires de la poissonnerie-volailles qu’ils avaient cédé à mes parents lorsqu’ils avaient pris leur retraite en 1962. Nous étions devenus un peu amis, et nous leur rendions visite de temps en temps. Monsieur Cambier n’avait qu’un seul sujet de conversation: La guerre de 1914. Je pense qu’il avait la maladie d’Alzheimer, mais qu’il souffrait encore aussi de stress post-traumatique causé par sa vie dans les tranchées. Une autre personne qui racontait pas mal d’anecdotes sur la Première Guerre Mondiale était Mademoiselle Simoëns, mon institutrice de ma classe de septième (CM2 de nos jours – classe que j’avais du reste redoublée), qui devait avoir alors une bonne soixantaine d’années au début des années soixante. Pour elle – comme pour la plupart de ceux qui avaient vécu pendant deux guerres mondiales – celle de 14-18 avait été beaucoup plus traumatisante et “difficile” que celle de 40.

Ma théorie est que ceux qui étaient encore en vie dans les années soixante et après étaient encore jeunes en 14-18 et que leurs plus belles années avaient été gâchées par la guerre. D’autre part, le nombre d’hommes morts au combat pendant cette guerrre est énorme, et bien des gens avaient perdu un ou plusieurs parents ou amis.

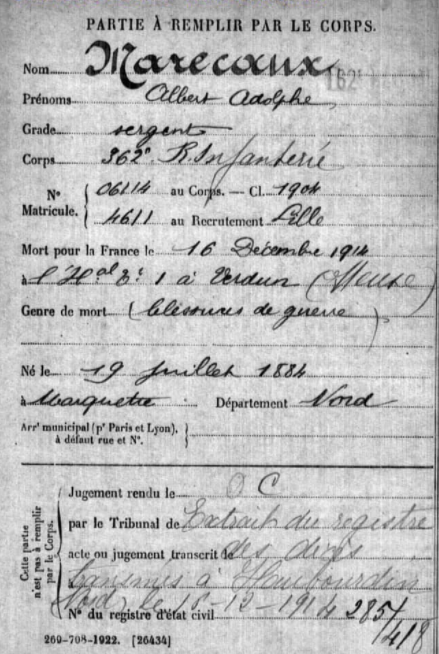

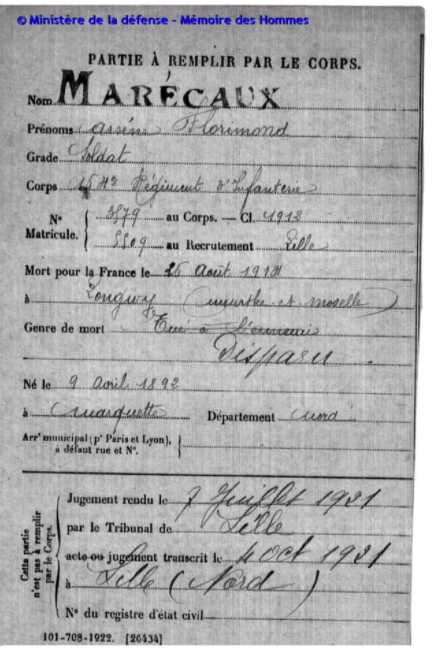

Dans ma famille, deux de mes grands-oncles, Albert et Arsène Marécaux (frères de ma grand-mère maternelle) n’étaient jamais revenus chez eux:

– Albert avait été tué à Verdun en décembre 1914 (mais pas dans la célèbre bataille de Verdun, où il est cependant enterré) et

– son frère Arsène avait été porté disparu.

– Raymond Dumoulin, le mari de ma grand-tante Marie (la soeur de mon grand-père paternal) but tué à Verdun en 1916.

– Mon grand-père paternel, Alfred Sauvage, avait été fait prisonnier de guerre moins de trois semaines après s’être porté volontaire et avoir rejoint les forces armées (il avait 38 ans et deux enfants et n’avait pas été recruté.) Il est très vite envoyé en Bavière, à Dillingen-sur-Danube, où il travaille pour le marbrier funéraire du village (mon grand-père était marbrier.)

Un article de la Convention de la Haye sur les prisonniers de guerre stipulait que si deux frères étaient prisonniers, Ils pouvaient être réunis. Mon grand-père fit donc venir son frère Albert, lui aussi marbrier, à Dilligen. Il fut consterné quand celui-ci (qui était marié en France) eut une liaison – et un enfant! – avec une jeune Bavaroise.

Quand il rentra en France, Albert confessa tout cela à sa femme, qui voulut au départ d’aller chercher l’enfant et de l’adopter, mais cela ne se produisit jamais. Je n’ai jamais cherché à trouver mes cousins bavarois mais mon oncle Luc, qui m’avait raconté cette histoire, me fit remarquer qu’il ne devait pas y avoir eu beaucoup de naissances à Dillingen entre 1915 et 1918. Un deuxième frère, Joseph (le jumeau d’Albert) revient aussi intact de la guerre.

Finalement, mon grand-père Alfred Sauvage conçut et construisit deux monuments aux morts de la Première Guerre Mondiale pour sa ville de Marcq-en-Baroeul (ce que j’ai trouvé sur ces projets est assez amusant), et fit un ex-voto qui se trouve à Notre-Dame d’Arliquet près de Limoges. Quand mon grand-père allait toucher sa maigre pension d’ancien combattant, à son retour chez lui, il disait toujours: “Je suis allé toucher ma retraite du com…battant.”

Photos:

– Documents concernant le décès de mes grands-oncles Albert et Arsène Marécaux ce dernier, porté disparu, fut ensuite déclaré décédé.

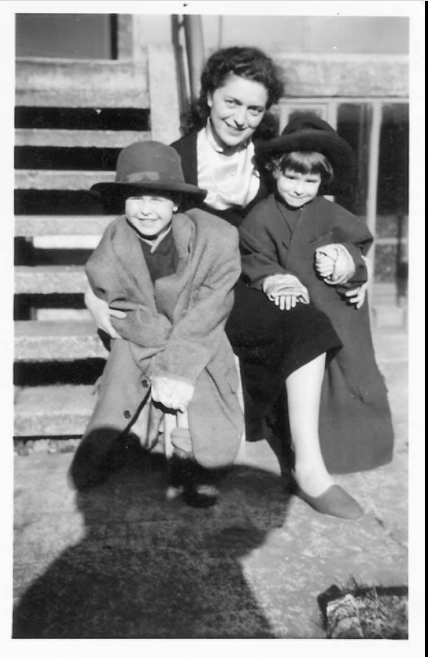

– Mon arrière-grand-mère, sur la tombe (encore temporaire) de son fils Albert.

– La tombe permanente d’Albert, à Verdun.

– Les monuments aux morts conçus et construits par Alfred Sauvage, mon grand-Père paternel.

– L’ex-voto gravé par Alfred Sauvage. Il se trouve à Notre-Dame d’Arliquet, près de Limoges.

– Portrait d’un camarade de captivité fait par Alfred Sauvage quand il était prisonnier de guerre à Dillingen-sur-Danube, en Bavière. Ce portrait se trouve dans un cahier que possède mon cousin Marc. J’ai scanné chaque page de ce cahier.

Translation:

I remember the veterans of the “Great War,” the war of 1914-18, and of the stories that I would hear about WWI when I was a child. Since I was born in 1952, when I was between 7-8 and 18 years old, many folks in northern France who had lived through the four years of that war were still alive. For me, the word “veteran” at the time designated those who had fought in the trenches between 1914 and 1918, and not French WWII veterans. My idea of those men was that they were all as old as my maternal grandfather who had not fought in WWI (he had completed his military service well before the war had started.) Thus, they were old, and often disabled – sometimes missing a leg or an arm. They would always be in the November 11 military parade. I especially remember Monsieur Cambier. He and his wife were the owners of the fish and poultry shot that they had sold to my parents when they retired in 1962. We had become quite friendly, and we would visit them once in a while. Monsieur Cambier talked only about one thing: The war of 1914. I think that he had Alzheimer’s disease, but he was still suffering from PTSD triggered by his life in the trenches. Another person who told quite a few anecdotes about WWI was Mademoiselle Simoèns, my 5th-grade teacher (a grade I had repeated), who must have been close to 65 at the time. For her – as for most of those who had lived through two world wars – WWI had been much more traumatic and “difficult” than WWII. My theory is that those who were still alive in the 1960s and later were still young in 1914, and the best years of their lives had been shattered by the war. Also, the number of men killed in combat during that war was huge, and many people had lost one or several relatives or friends. In my own family, two of my great-uncles, Albert and Arsène Marécaux (my maternal grandmother’s brothers) never returned home: Albert was killed in Verdun (but not in the famous battle of Verdun, although he is buried there), and his brother Arsène was MIA. Raymond Dumoulin, my great-aunt Marie’s husband (Marie was my paternal grandfather’s sister) was killed at Verdun in 1916. My paternal grandfather, Alfred Sauvage, was captured by the Germans just a few weeks after he had volunteered and joined the army (since he was 38 and had two children, he was not drafted.) He was very soon sent to Dillingen on the Danube, where he worked for the village tombstone maker. An article in the Convention of The Hague on Prisoners of War stated that if two brothers were prisoners, they could be reunited. So, my grandfather managed to have his brother Albert, who was also a tombstone maker, join him in Dillingen. To his utter dismay, Albert (who was married in France) had an affair – and a child! – with a young Bavarian woman. Upon his return to France, he confessed his indiscretion to his wife, who wanted to find and adopt the child, but that never happened. I have never sought to find my Bavarian relatives, although my uncle Luc, who told me that story, mentioned that there must not have been a lot of births in Dillingen between 1915 and 1918. A second brother, Joseph (Albert’s twin brother) also came back intact from the war. Finally, my grandfather Alfred Sauvage designed and built two WWI memorials in his hometown of Marcq-en-Baroeul (What I found out about this is kind of funny), and made an ex-voto plaque that can be seen at Notre-Dame d’Arliquet near Limoges. When, after the war, my grandfather would go and get his meager veteran’s pension, when he walked into his house, he would always declare: “I got my “com… battant”’s pension (literally, “fighting asshole” pension.)Photos:- Documents about the deaths of my great-uncles Albert and Arsene Marecaux. The latter, who was MIA, was declared dead later on. – My great-grandmother, near the still temporary grave of her son Albert at Verdun.- Albert’s permanent tomb, in Verdun. – The WWI memorials were designed and built by Alfred Sauvage, my paternal grandfather. – The ex-voto plaque engraved by Alfred Sauvage. It is in Notre-Dame d’Arliquet, near Limoges. – Portrait from one of his friends who was a prisoner with him, drawn by Alfred Sauvage when he was a prisoner of war in Dillingen on the Danube in Bavaria. This portrait is one in a notebook that my cousin Marc owns. I have scans of every page in this drawing book.

Je me souviens #15: de ma découverte de Paris

– le Bateau-Lavoir et nous raconta son histoire;

– le Marais, où évoqua la rafle tragique du Vel d’Hiv;

– la Place des Vosges et la maison de Victor Hugo;

– Le Quartier Latin et la Sorbonne (du temps où on pouvait encore y entrer librement),

– le Panthéon,

– les Arènes de Lutèce et

– la rue Mouffetard. Et bien d’autres lieux encore.

Et à chaque fois que je suis à Paris, je me souviens de Tatie Renée.

I remember discovering Paris, mostly thanks to my godmother, the ultimate Parisian. For my brother and me, she was Tatie Renée. Born in May, 1913, she was my mother’s cousin. Her father, my maternal grandmother’s brother, was killed in combat in 1914 and her mother was either living in Paris at the time, or relocated there shortly after her husband’s death. In any case, Tatie Renée was raised on the Île Saint-Louis (now an area of Paris unaffordable to most people.) She must have had an interesting childhood, because one of her best friends at the time was Odette Joyeux, who was to become a famous actress (her first husband was the famous French actor Pierre Brasseur [1905-1972], with whom she had a son, Claude, also a very famous French actor [1936-2020.]) Tatie Renée had told me one day that her buddy Odette Joyeux had asked her to go and visit the write Colette, but she had chosen not to go, which she had regretted bitterly afterwards!

Do these memories pique your interest or anything in your memory? Or if you have questions please ask Elisabeth in the comments below.

If you are a French language student – please join Judy MacMahon as she uses my memories as a study exercise. Which vocab or grammatical points or expressions are unfamiliar to you? Please share in the comments below.

This series began here “Je me souviens” #1-#7

And here you’ll find “Je me souviens” #8-#14

To discover “Je me souviens” #15-#18, you’ll discover it here