Interview: Marina Ferretti Bocquillon, Musée des impressionnismes – Part 2

This interview is in English. Click here to read it in French.

Click here to read the first part of the interview.

Here is part two of our meeting with Marina Ferretti Bocquillon Scientific Director of the Musée des impressionismes in Giverny, and curator of the Radiance: The Neo-Impressionists exhibition in Melbourne.

How important is the historical and social context of this movement?

Politically, the 19th century saw the complex introduction of a republican regime, with revolutions taking place right throughout the century. The last of them, la Commune de Paris (1871), was stamped out by a bloody repression which had a lasting impression on artists like Maximilien Luce.

The working class built itself up and contributed to the birth of socialism and trade unions. In the exhibition, the works of Maximilien Luce and Georges Morren reveal their involvement with the workers.

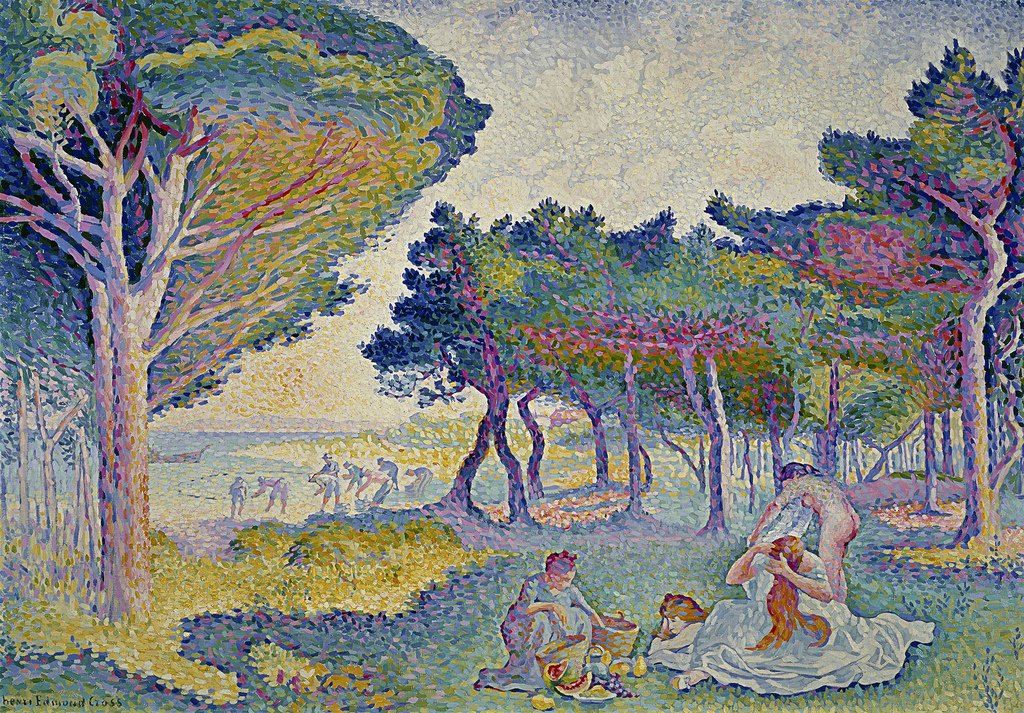

At the same time, anarchism was gaining importance and resonated wall with artists throughout the 1890s, particularly with the neo-impressionists who, except for Seurat, were nearly all supporters of Pierre Kropotkine’s ideas. Pissarro, Signac, Cross and Van Rysselberghe all aspired to an ideal society where human activity would develop in harmony with nature. Hence the idyllic landscapes of France’s southern Midi region that are on display in the exhibition.

What major changes took place during this period?

It is important to remember how significant the development of technology and science was during the 19th century, and the impact that had on the artistic world. It began with the invention of the Conté crayon in 1795, and followed on coloured paints in tubes and fold-up easels which made painting outdoors much easier for artists.

There was also the industrialisation of paper production which allowed artists to draw freely. Lastly, the developments in chemistry helped increase the gamut of pastels available, and of course the scientific research carried out on the perception of colours which became fundamental in the elaboration on neo-impressionism.

What can the public expect to discover about the Neo-impressionist movement?

Beyond the pleasure of the explosions of colour and light, the Neo-impressionists works describe a very unique historic period where our modern tendencies began to open up.

The industrial revolution brought about the birth of a middle class which was quick to become a driving force of the economy. This is the basis of the consumer society which was set up and contributes hugely to our lives today.

In Haussmann’s Paris, fashion and big shops became a focal point of daily life. The implementation of street lights helped build up night-life, the opera, the café concert and the circus. It was also a significant period for the development of railways.

The notion of leisure was also completely new. On Sundays, even the most modest of city-dwellers would visit the banks of the Seine river and in summer, the more privileged citizens would make the most of the seaside. There was already a sense of nostalgia for unspoilt nature, and sports and tourism were growing in popularity – which is all still very relevant today!

Neo-impressionism (a.k.a. Pointillism) is often considered an extension of the Impressionist movement, but in reality, it was more so a counter-development to Impressionism. Why?

Similarly to the impressionists, the “neos” depicted modern life and were interested in the translation of light and favoured the use of bright colours. But unlike their predecessors who focused on capturing fleeting moments, Seurat and his friends were more interested in seizing the true essence of a particular scene or landscape. This is why they synthesised their shapes and eliminated details to evoke another geometric reality.

The neos also hoped to bring out their colours and avoided mixing them. They like Eugene Chevreul’s theories on the perception of colours and “optical mixtures”. Thus they put little touches of pure colour on their canvases, allowing the viewer’s eye to appreciate the synthesis of tones. It is a very long and laborious process that can only be achieved when painting outdoors.

Translation by Anna Pitt

Image credits:All images courtesy the National Gallery of Victoria.