Only One Promise

Only One Promise is a nonfiction book recently written by Kim and Mark Jespersen

Only One Promise is a nonfiction book recently written by Kim and Mark Jespersen. Mark did most of the writing, but Kim was always at his side listening, editing, arguing, and supporting the work. The manuscript is currently with a potential publisher and, hopefully, will one day be available in English and French. On croise les doigts.

Introduction

When Kim and Mark Jespersen stumble upon a bundle of handwritten love letters written in 1926, at a flea market in the South of France, they can’t shake the feeling that they’ve found something meant to be uncovered. It’s 2008 — the world is reeling from the financial crisis, and their own lives feel uncertain. But these fragile pages, penned nearly a hundred years earlier, ignite a search that spans a decade and two continents.

As they unravel the story of Claude and Elsa — a young journalist and an American artist separated by distance and desire in 1920s Paris — Kim and Mark begin to see echoes of their own marriage, their risks, and their hopes. What starts as a historical mystery becomes something deeper: a reflection on how we live and love, no matter the era or the place.

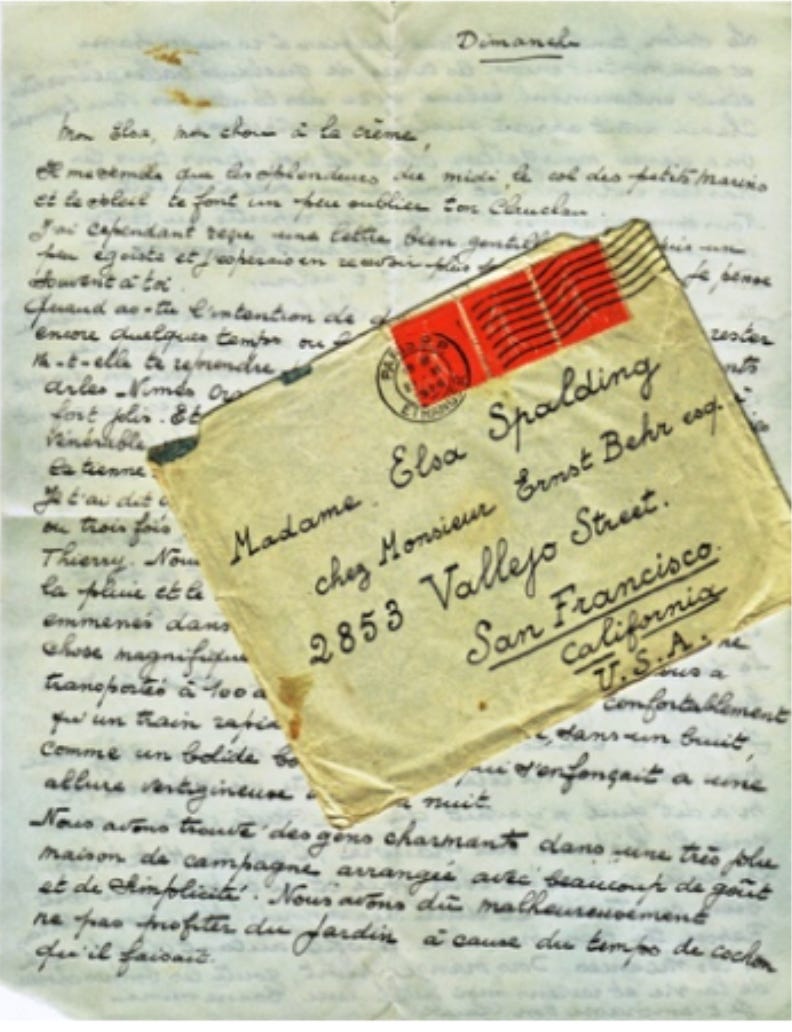

There were eight letters in all, dated Paris, 1926. My wife Kim found them, eighty-five years later, at a flea market, in a box of junk destined for the trash. They looked promising, though we couldn’t read French, not yet. Tantalizing clues and a conviction that we’d stumbled on something important pushed us to spend the next ten years of our lives on an incredible journey.

It began in 2008. It was an exceptionally cold winter in Maine that year; the temperature had plummeted just like our retirement account. We were worried about what lay ahead—most people were. Maybe that’s why we responded as we did to Patrick’s email. Our old friend lived in France and was fond of sending us notes that said, “Why not visit now?” My answer was always, “work,” a response that would inevitably lead to a reprimand. “In France, we work to live, not live to work, like you Americans.”

He had a point.

It was mid-January when we landed in Nice, but it felt more like a warm day in May. You could smell the earth, the flowers, and the sea-breeze coming off the Mediterranean.

We were enchanted. We were hooked. And when our return flight was delayed for three days, we ended up buying a 700-year-old house we couldn’t really afford.

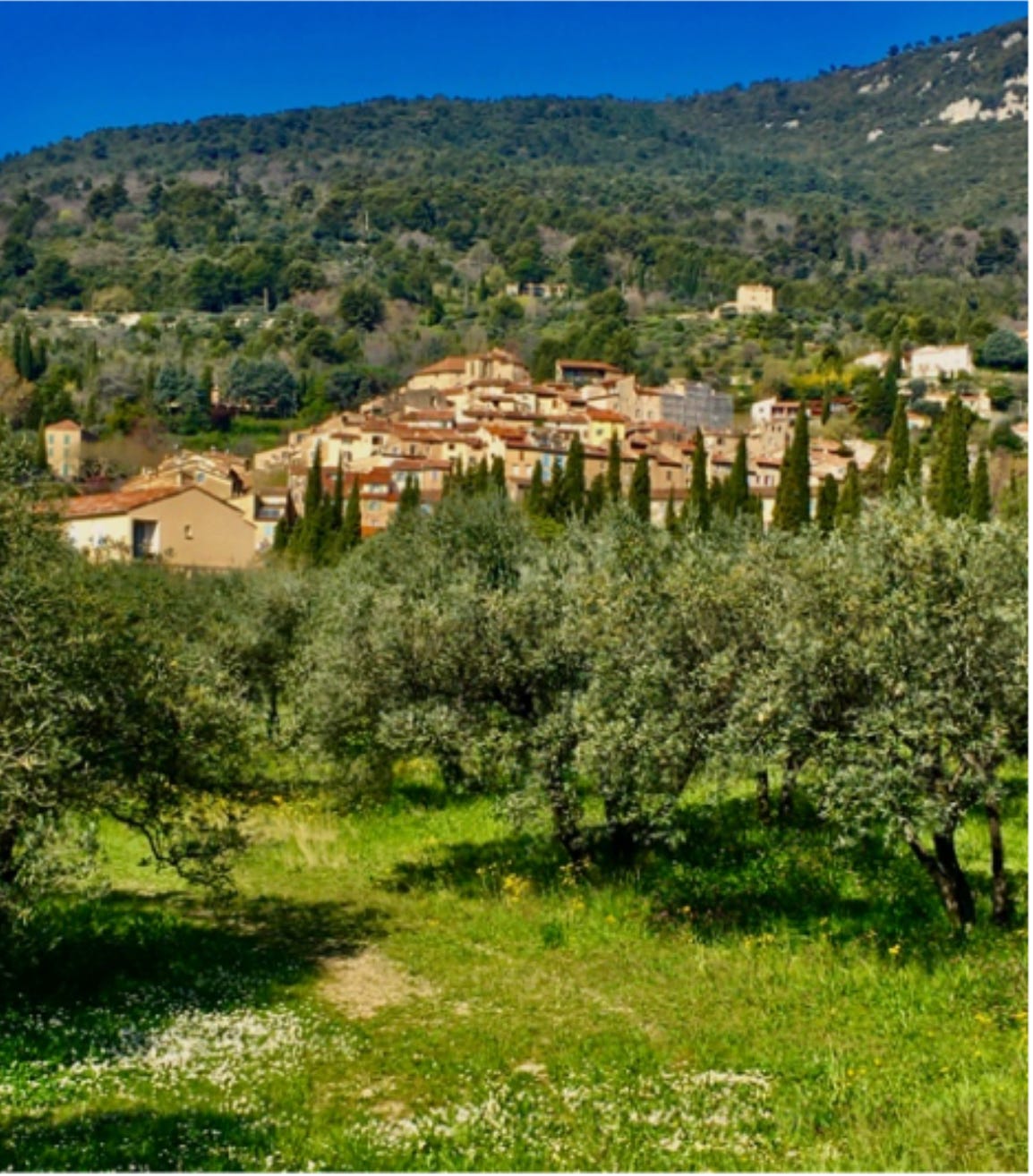

Kim and I had wandered into a local real estate agency “just to look” at some listings. It was, we thought, a way to kill some time before flying back to the States. The realtor, Eric, was taking a nap at his desk, but he recovered quickly and took us to see some properties in Seillans, the little hill-top village that overlooks the plain between the southern Alps and the Esterel mountains along the coast. “For thousands of years,” he explained, “the locals fought off plagues, Saracen pirates, and Roman armies coming up from the coast to pillage and plunder.” He must’ve retold that bit to hundreds of wide-eyed potential home buyers.

Each of the properties we saw in our modest price range had at least one or two insurmountable problems—tiny windows, water around the foundation (never a good sign), or a view of rusted and abandoned Citroën trucks. It was only when we felt disappointed that we realized how serious we were about buying a house in France.

“There is one more property I want to show you,” Eric said. “It’s just been put back on the market.”

The house was tiny but spellbinding.

A steep spiral staircase brought us up to tiled floors, rough plaster walls, honey-colored raised panel woodwork, wrought-iron hardware, and big windows that let in the sunlight. One more flight of stairs led to a rooftop terrace with a breathtaking view of the rolling green hills and a misty valley down below. On the horizon, twenty miles away, the Esterel mountains. As if on cue, the village church bells rang out.

I looked over at Kim.

“I think our Navajo rugs would look just right on the walls, don’t you?”

If Kim was beginning to decorate, I was pretty sure we were about to become the owners of an ancient home in the south of France.

It took some quick thinking to arrange everything, but in three days, we had bought the place lock, stock, and some old bistro wine glasses.

We were thrilled with the antique furniture, the earthenware jugs, and the old, mismatched plates. The only thing we didn’t like were the cheap enamel pots and pans. That’s what sent us to the flea market. Our first venture out was to the Monday morning market in Nice. Prices were on the high side, and everything marked Le Creuset, the cookware Kim was looking for, was out of our range. In search of a bargain, she’d stopped suddenly to examine the hodge-podge of dolls, dishes, and costume jewelry on three rickety tables along a back wall.

“You won’t find any Le Creuset pans here,” I said, looking around at the offbeat selection of junk. But Kim didn’t hear me. She was down on her knees, picking through some cardboard boxes under a table.

I went over to look at a guitar propped against the wall. Noticing my interest, an older lady rose from her lawn chair and drifted over. The guitar, a six-string classic, was dented, covered with dust, pigeon poop, and a flower-power sticker. I plucked the few old strings still on the guitar, then put it down.

The lady smiled at me and said “C’est bon”, pointing to the guitar. She had only one tooth that I could see, and the guitar only had four strings, but it had the unmistakable tone of a fine instrument

Meanwhile, Kim had fished out a handful of letters written in 1926. She waved them at me with a glint in her green eyes that I’ve grown to respect over the years. “The handwriting looks so interesting,” she had said, handing me the letters and a few old photos. The lady with one tooth smiled. If I understood her correctly, she said if I bought the guitar, we could have the letters, as a gift, “C’est un Cadeau.”

Curious by nature, and with little else to guide us, we set off to uncover who wrote the letters. The quest was pure escapism, and we spent most of those early years in France searching for someone else instead of worrying about ourselves, complete strangers in a foreign country. And we relished those exciting times together; ecstatic when we uncovered something new, frustrated when we didn’t, and, just as often, confused or quarrelsome when what we did learn didn’t agree with our personal feelings.

There were many arguments around our old kitchen table.

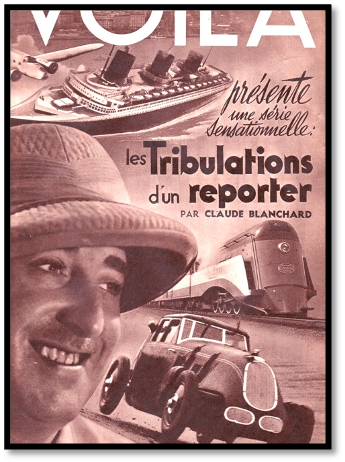

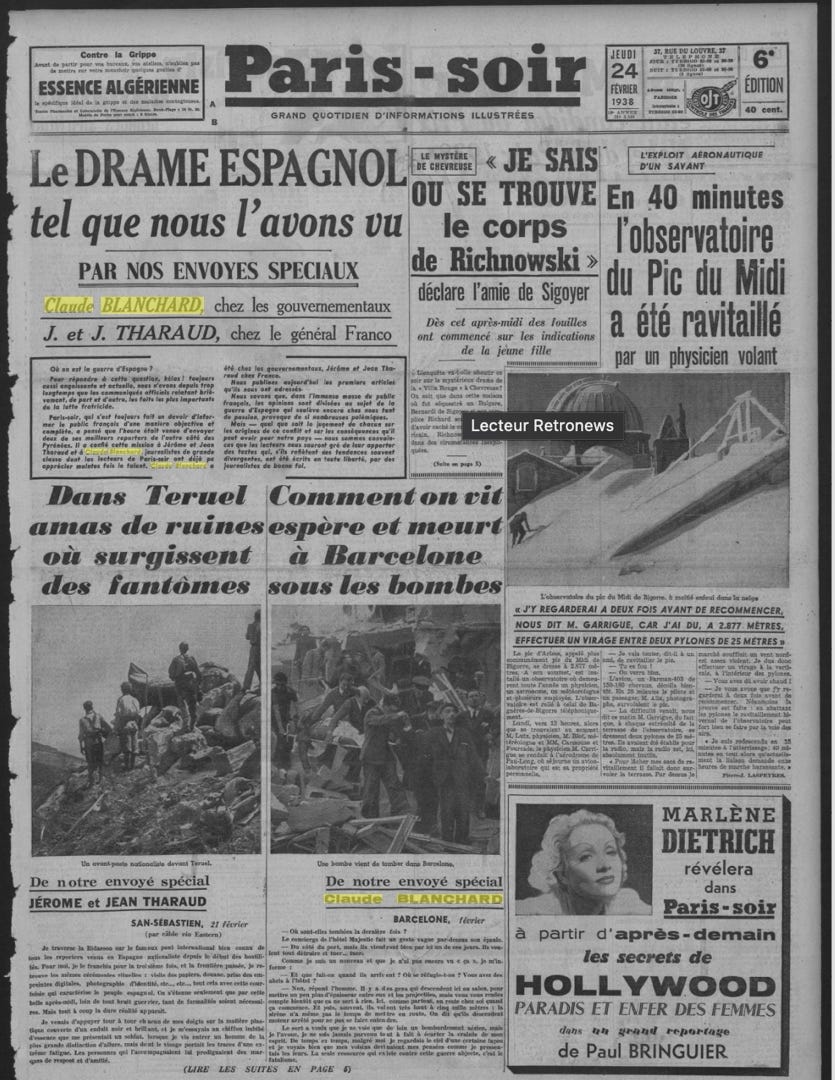

The letter writer, we finally learned, was Claude Blanchard, an ambitious young French journalist. In 1922, he had collided head-on with Elsa Behr Spalding, an American artist studying at the Académie Julian. Four years later, she broke off their affair and left Claude standing on the platform at the Gare de Lyon, watching her train disappear in a cloud of smoke.

It was a scene right out of the classic French film, “The Umbrellas of Cherbourg,” with Michel LeGrand’s lush theme song playing in the background. The next day, Claude composed the first of his letters saying, basically, that if it takes forever, I will wait for you.

Our dogged research took us into the homes and lives of interesting and enchanting people who would share their stories or point us in a new direction. Many of these encounters led nowhere, but a precious few kept us going. One memorable woman, who had learned it the hard way, encouraged us to persevere. “You must continue your journey. Don’t be dismayed. We all find what we are looking for if we keep going.”

And so we did.

Through our research, we were able to piece together the remarkable lives of Claude Blanchard, who, between the wars, had fashioned himself as the quintessential foreign correspondent, and his American wife, the sculptor Elsa Behr Spalding. Theirs is a story of a couple deeply in love during a remarkable generation. From legendary friends, like Sylvia Beach and Gertrude Stein, to a long list of lesser-known artists and actors who made up their close circle in Paris.

Our story lays bare the experience of these artists and writers, as well as the ordinary young men and women who, in 1914, rushed to defend their country, and who, having survived the Great War, spent the following years searching for some meaning to it all. Theirs is a tale that will help restore faith in humanity among readers looking for a bit of rationality in an increasingly irrational world. Claude wrote with only one thing in mind: to tell the truth.

Truth be told, we never set out to write a book. We were just two naïve yet curious Americans who, through a handful of old love letters written in a language we couldn’t read, were having the time of our lives.

In the end, after nearly ten years of work, we thought that by telling their story, we were doing something important for them. In fact, as Kim reminded me one day, they’d done much more for us. Without realizing it, as we came to know this incredible couple, we grew closer to each other and our new life in France.

External Links:

Elsa Behr Blanchard - a link to my previous article in MyFrenchLife™ Magazine

Images:

Blanchard was a foreign correspondent for Paris-Soir for many years.

Introducing Contributor, Mark Jespersen

Immerse yourself in all of Mark’s articles on his Contributor page.

What an amazing project. I am impressed by writers who can dive and delve into a story for years, and it's wonderful that you were able to work on it together.

Fascinating love story -I would love to learn more.