The 3.5 Emotional Stages of Living Abroad

I'm currently stuck at "guilt," hoping to achieve "acceptance."

My therapist told me I don’t have to feel this way, but I think I’ll have to pay her to tell me a few more times before it really sticks: I feel very guilty for living abroad.

As with most crimes, I didn’t start out feeling guilt. No, for a few years I was thrilled that I got away with it. I also didn’t expect to stay for as long as I have, so I never thought I’d have to deal with the consequences of my actions. I’d likely be back before anyone missed me, or before I missed anybody. Not that I ever put an end date to the French experiment; I always said we’d stay two years minimum to give it a real honest try, but also was careful to never set a maximum so that I couldn’t be held to it. It turns out that after six months I couldn’t imagine ever moving back to the US. Oops.

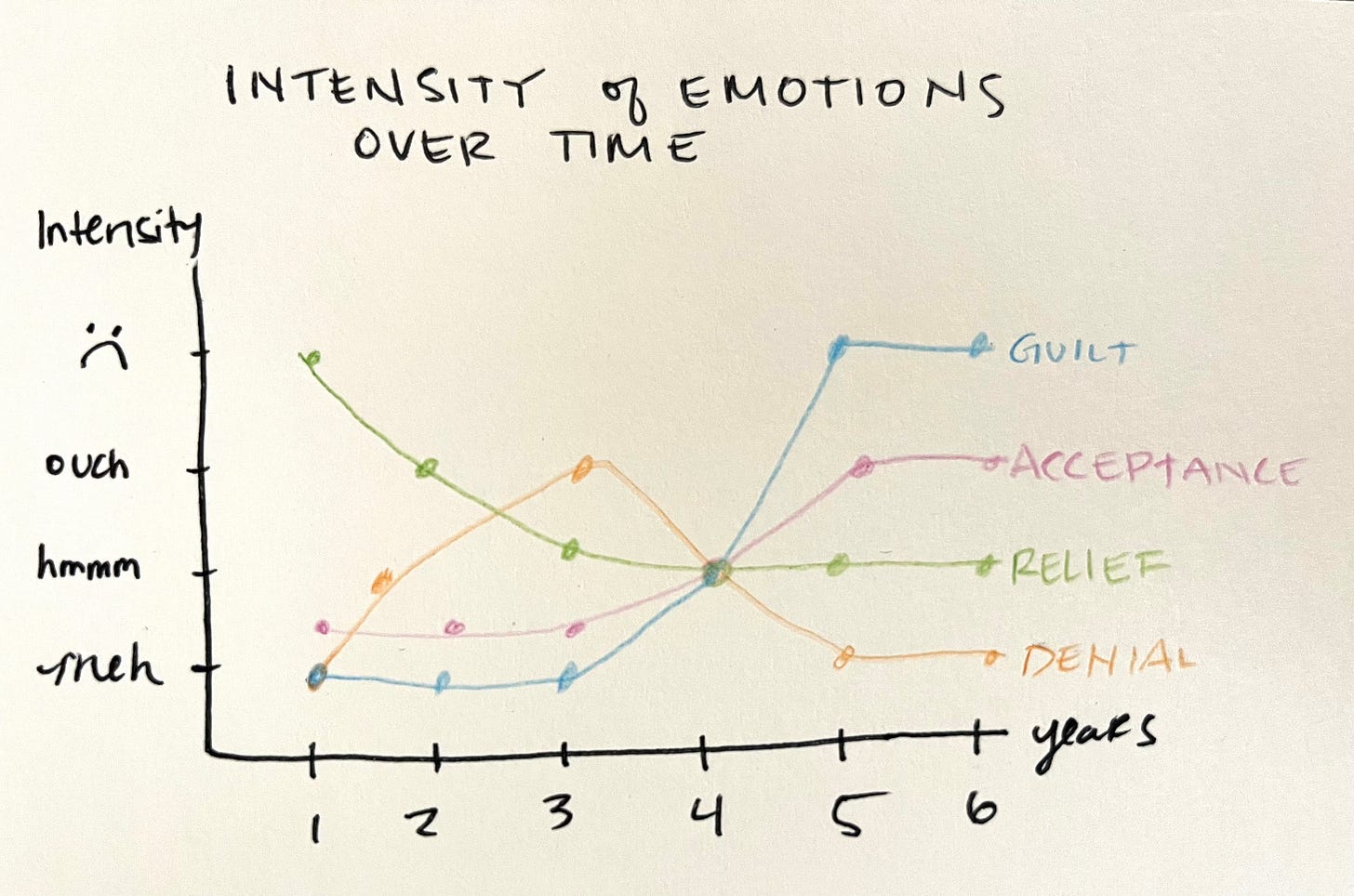

When you imagine your move abroad, you think only of sipping spritzes on terraces 24/7 and being able to afford your medications, but never the emotional complexity. Maybe because I never moved from LA county for the first 32 years of my life, I didn’t yet comprehend that when you move, it makes you feel stuff. I just thought I’d be doing the same shit but further away. But five and a half years on, I can now look back and see the whole range of emotions that the move kicked up, and that they actually only get worse, not better, the longer we’re away.

Yes, it began with relief, but has since transitioned to guilt by way of denial. I’d love to get to acceptance, but I fear that I may just stall out forever in the guilt zone, especially while the price of eggs in the US soars as the president hosts a used car commercial on the White House lawn.

Alors, the emotional stages of moving abroad, particularly in times of ketamine-fueled stagflation man-child tech broligarchy crisis.

Relief

The whole thing started out as relief: the buffer of distance and time, the 9-hour delay on emails, the very tiny available window for calls that resulted in fewer calls, then eventually almost no calls just like I always wanted (I hate calls). I had just gone through a two-year extended professional burn-out, it was that one dude’s first term in office, and I had cortisol face from both; I had earned the right to give all my stuff away and move to France without a thought as to the consequences.

Then the pandemic cemented my relief because, while it was a crap situation everywhere, our guy in a suit at least acknowledged science and seemed to have a plan, whereas the USA’s guy in a suit said maybe ingesting disinfectant could be interesting. Also, his suits always sucked, still do. So as much as I felt a little guilty for leaving all my people behind while the world was potentially ending, it seemed like the move anyone would make if given the chance.

Sadly, the relief stage wanes after a while, hedonic treadmill and all. The novelty of being more relaxed begins to just feel normal as the move and its benefits weren’t novel anymore and I forgot how much my medical expenses were in the US. But that doesn’t mean I felt bad about the move yet. My brain had one more party trick to hide my feelings from me. Enter denial.

Denial

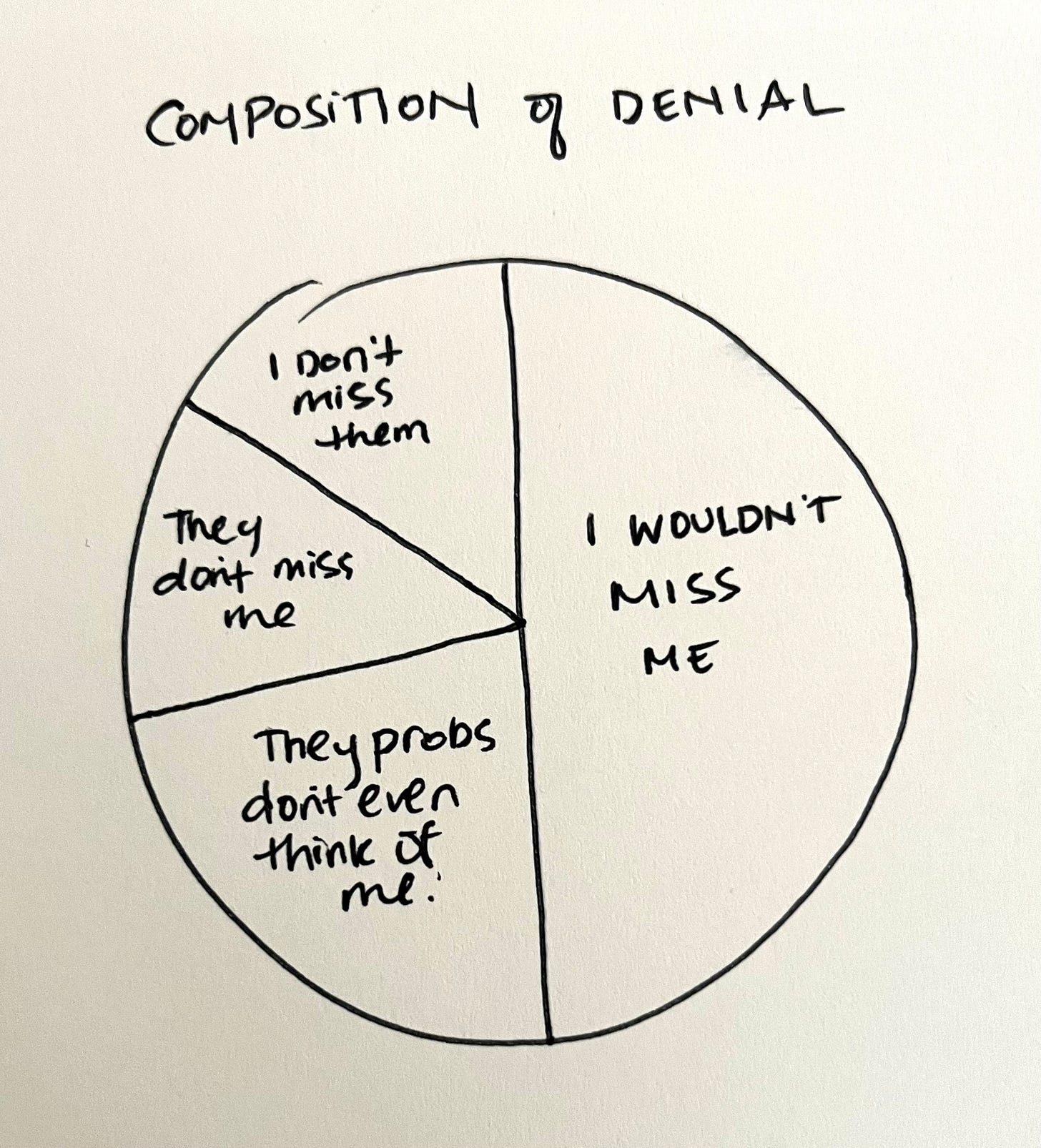

I’m not sure that everyone necessarily goes through the denial stage, or if they do, if it is rooted in the same logic. The logic behind my denial is that I assume no one misses me. If you have a higher sense of self worth than I do, maybe you get to skip denial, but that means you will also miss out on all of the river in Egypt jokes.

Call me humble, call me self-loathing, but I’m always shocked when someone says that they’re sad that I moved or that they miss me or that they have ever even thought of my existence when I’m not in the room, trying to get their attention. So I just assume that while I’m way over here in France, everyone I know and love is happy over in America doing their thing—a thing which I doubt I could contribute to or that they’d want me to take part in. I barely like me around, so clearly no one else possibly could. That’s my logic, anyway, and it worked for a while.

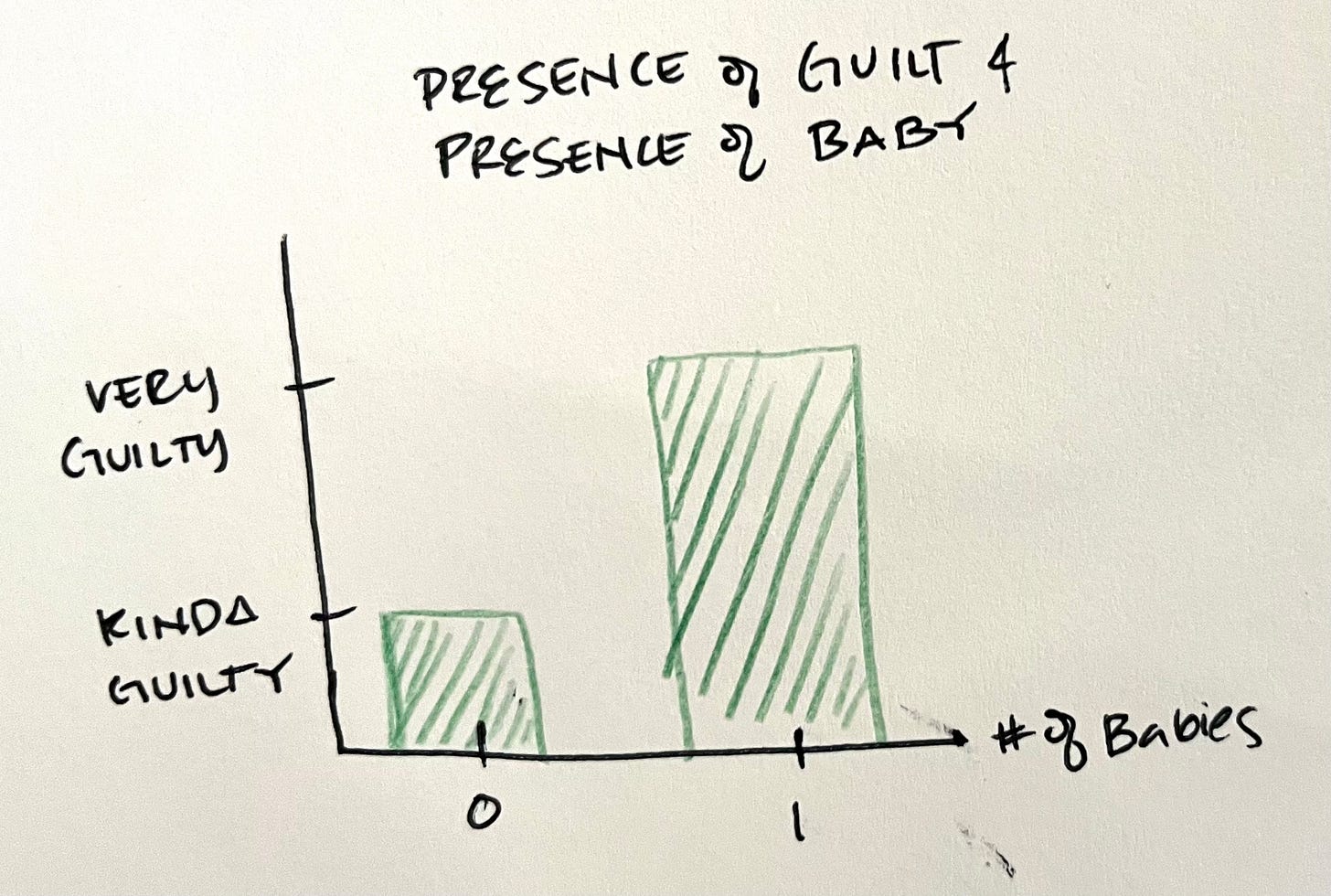

Denial is what got me through years three through four of being far from home. If you have any addicts in your family, boomers, or Republicans, you know the elastic power of denial. It can stretch for years and years with nary a problem. It can also snap very suddenly, and that’s what happened when I had a baby. Just like that, denial didn’t work anymore and I headed into guilt territory.

Upgrade if you’d like to make my day.

Guilt

While I had felt pangs of guilt now and then after moving, it had always been easy to ignore them via a cocktail of relief and denial. But my baby ruined the illusion.

Whether I’m miss-able or not varies depending on who you’re talking to, but everyone who knows my baby can’t get enough of him. Not to be annoying, but did you know that I gave birth to the single most handsome, charismatic, adorable, intelligent, articulate, and literate baby to ever grace this earth? Well, I did, and there was no more denying that the distance was painfully great once he arrived. So now guilt is something I feel every day that I keep him far from his American family.

Why don’t we just move back? Because then he’ll be far from his French family, and my husband and I will be far from seven weeks paid vacation and affordable childcare. So I think I’m just doomed to constantly feel guilt. And is that so bad? Well, given that the guilt can cause an actual physical sensation in my tummy, yeah, it is kind of bad. It’s like my animal body is begging me to do whatever eliminates unhappiness or pain from the people in my life, and my human brain is saying we’re not going to do that. The tension between the two is quite unpleasant.

I’ve discovered there are two different flavors of guilt: something akin to survivor’s guilt, and something else that I’ll call GOMO.

Survivor’s guilt I usually feel when I wake up to news alerts of some fresh American nonsense the country is putting itself through that I only have to experience from a distance. Typically I go to sleep without a care in the world then wake up to news of insurrections, fumbled elections, almost assassinations, and I feel bad that I slept through it and won’t have to deal with it directly. What’s happening in the US still applies to me; I’m American and pay American taxes and vote and bleed red, white, and blue (we’re looking at treatments). But I get to experience it through the filter of a time delay, physical distance, language difference, sometimes it won’t affect my day-to-day. And because I don’t have to deal with it first hand, I feel guilty.

I mean, it’s not all wine and roses all the time over here, either. I can’t get blue Gatorade or spicy salsa, there’s plenty of political drama and police brutality here as well; don’t forget that everything in life is a trade-off. But because I’m not fully fluent in French, I still posses the lovely ability to tune out the French language when I want to. I have to concentrate to understand the radio or TV, and so if I don’t feel like hearing it, I can just not, delivering a delicious distance from French political drama when my nervous system needs it. I don’t do it all the time, in fact I take seriously my responsibility to know wtf is going on in this country (though the lady that interviewed my for my French citizenship tended to doubt it). Still, it’s a nice option to have, and one that is harder to exercise in the US.

The other brand of guilt, GOMO, is obviously (not particularly cleverly) “guilt of missing out,” and it’s the type of guilt I hadn’t bargained on. It’s the guilt of not being there for the important life stuff that keeps happening even though I’m far away. I used to try to fly back for every wedding, every funeral, every so often just to maintain friendships and my knowledge of the LA restaurant scene. But since the baby, I can’t hop on a plane with the same speed and ease I once could, so I miss out on a lot of stuff. Missing out is a punishment in its own right, but the guilt of letting people down makes it even worse.

This particular guilt began to hit when I was pregnant and realized that I likely wouldn’t see my family again until after the baby arrived. I had to admit to myself that I needed to not fly for a while—planes made my torso balloon like a can of Coke, painfully—it was a new sensation to let people down for my own wellbeing. This is how I learned from my therapist that I don’t need to feel guilty. I told her of my guilt and she brushed it off, told me my only job was to do what was best for my child, husband, and myself. Pretty good advice, and I now pass it on to you, save you the $100 for the session.

Acceptance

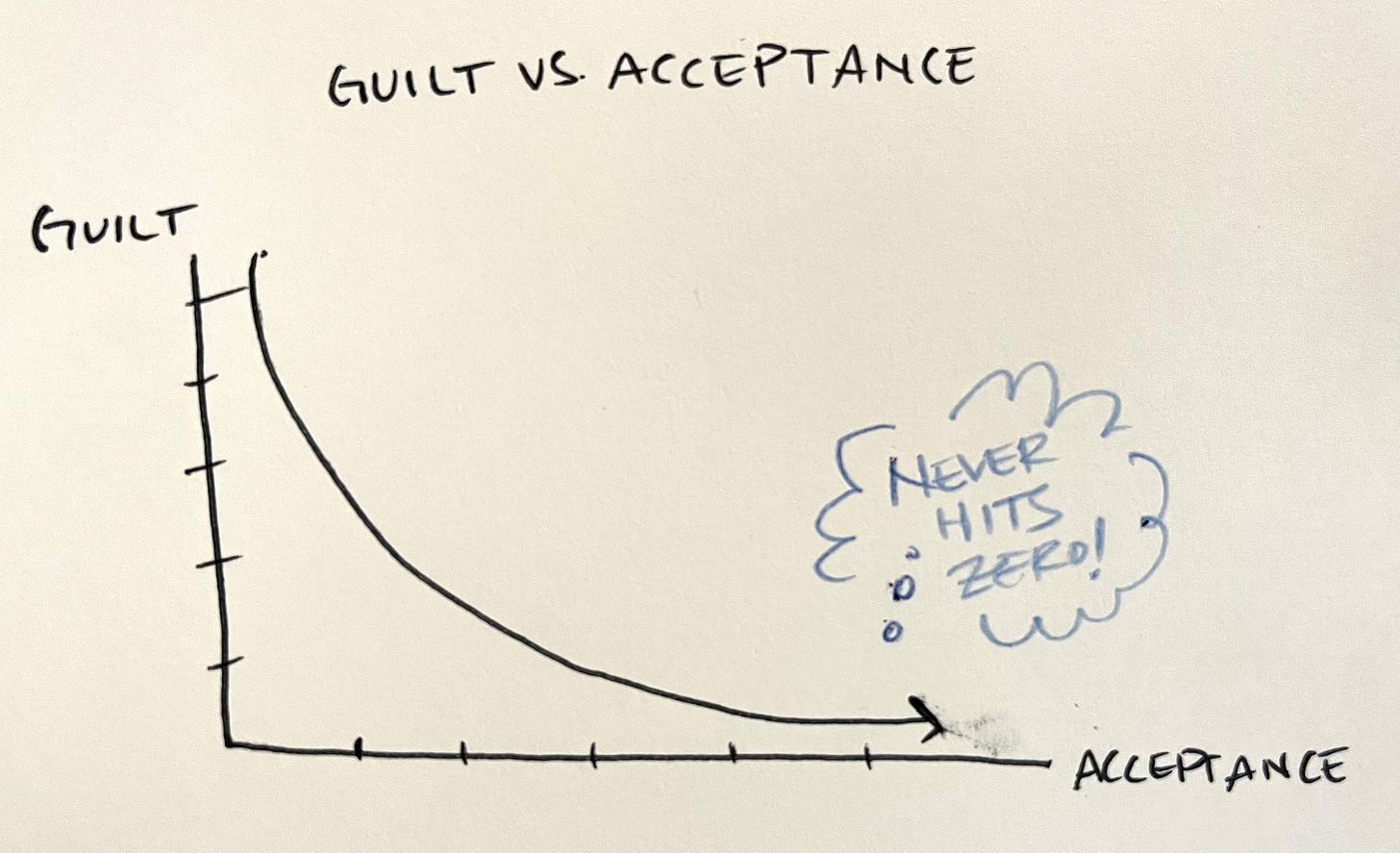

The advice from my therapist may be the closest I’ll get to that coveted, juicy, peaceful acceptance. Whenever the guilt creeps up, I ask myself what’s better for my little family and then I just do that. It takes a lot of intentional, conscious effort to get there though, which kind of feels like the opposite of acceptance to my thinking. Shouldn’t acceptance just happen on its own as a natural consequence of my becoming so emotionally evolved and wise? Trying to accept feels like the antithesis of acceptance, but what do I know.

This has led me to a new theory of acceptance: I’d like to posit that acceptance isn’t something we necessarily feel, but is more of an action. I act from a place of acceptance by staying in France, missing some holidays and weddings, feeling guilty as hell but sticking to the plan we’ve made for our family. That’s some guilt-rejecting, acceptance-aligned action if I ever saw it, never mind that I still feel awful. God, being an adult sucks, especially when you do mature stuff like choose where you live based on childcare or lack of GMOs.

But even if I am indeed acting from a place of acceptance, I sure don’t feel it. That’s why I’ve reduced the “acceptance” emotional stage to a half stage, 0.5. Acceptance is an asymptote emotion, you can get closer and closer but it’s impossible to ever totally arrive.

And So…

I hate admitting to myself that I can’t have it all, but until they invent teleportation (or the government stops hiding it from us!), I can’t have it all. I just have to limp on, making grown-up decisions despite my emotions like some kind of therapy-ed, mature thirty-something. Gross.

Do you live far from home? Does it make you feel things? What are your tips for when the emotional chickens come home to roost? How do you keep the mean reds at bay?1 Any advice more fun than “deal with it”?

BTW, “mean reds” is a reference to Breakfast at Tiffany’s, not a reference to mysanthropic Republicans. But if you took it as the latter, I suppose the question still stands.

Introducing Contributor, Selby Chambers

Immerse yourself in all of Selby’s articles on his Contributor page.

I agree with the below -- the main and most legitimate factor leading to guilt is being away from family. It was only once I lost both parents that that low-grade weight disappeared and I was able to finally tell myself "this is TRULY home now." I don't want to depress you by telling you how many years in that was. However, as you mention, watching your own children thrive here is the best antidote.

Brillaint framing here. That asymptote metaphor for acceptence captures something most people miss about longterm expat life. I moved to Berlin few years back and remember thinking the homesickness would fade, but instead it just morphed into this low-grade background hum. The guilt stuff esp rings true when family events happen and i'm just watching stories on Instagram instead of being there in person.