The Siege of Calais and Auguste Rodin’s Burghers of Calais

The Hundred Years’ War; the Siege of Calais and the Burghers of Calais as portrayed in opera, paintings and Rodin’s renowned sculpture

Republished with edits

Introduction:

I first came across Auguste Rodin in late Summer 1987 in London, where I was completing the final part of my M.Sc. in Geophysics at Imperial College. It was a summer of U2 and Madonna concerts in London and geophysical fieldwork in the wilds of Snowdonia, Wales. I was soon to start my training and 28-year career in education, having decided that the oil and gas exploration industry was ultimately not the career for me. Whilst I loved travel (still do), I desired a home of my own, love and a family, where I could put down my own roots.

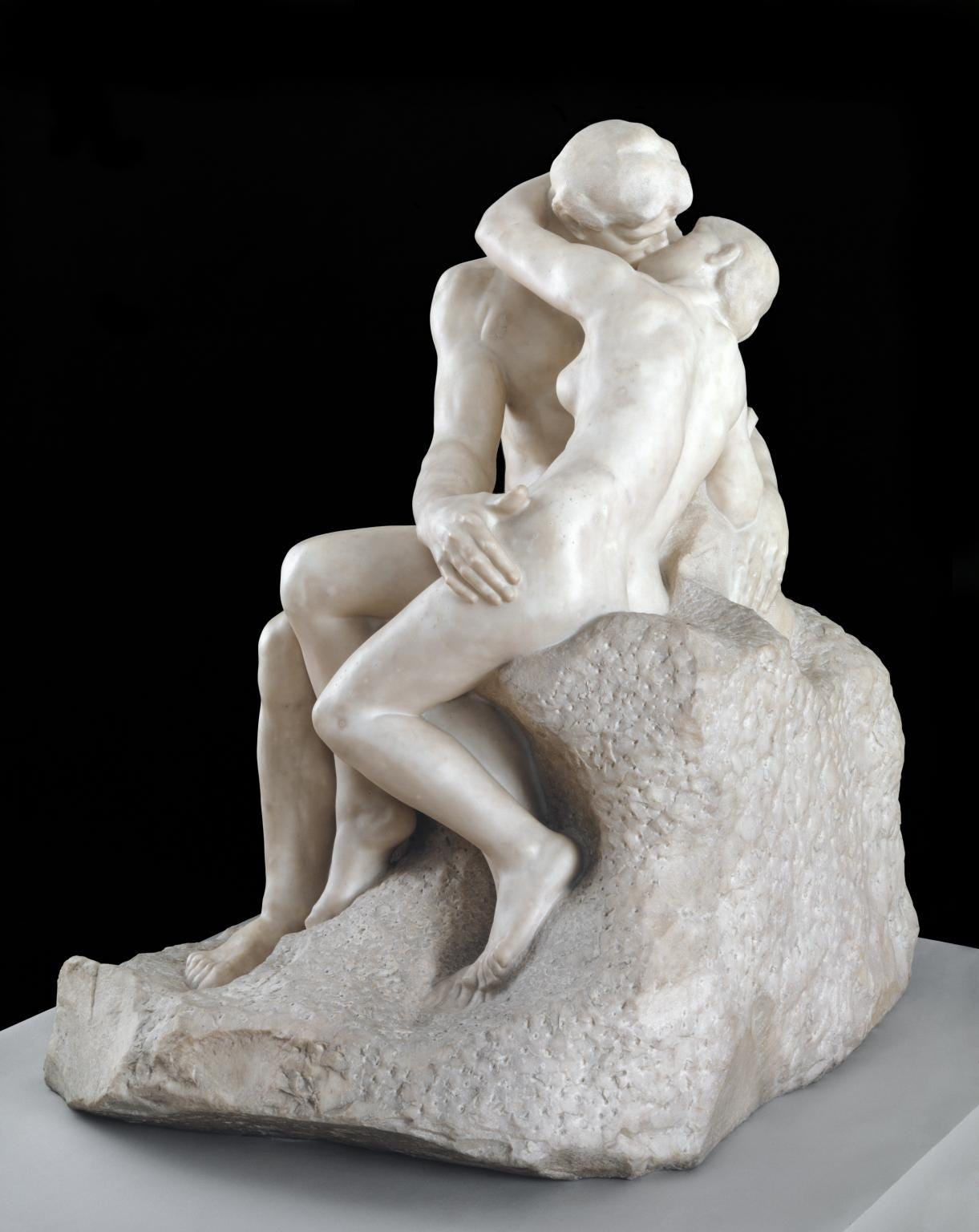

A fellow student and friend took me to the Tate museum, where I stood in awe when I came upon Rodin’s The Kiss.

The Kiss, 1901 - 1904, Auguste Rodin. Tate, Purchased with assistance from the Art Fund and public contributions 1953, Photo: © Tate

These days, every time I disembark from the Dover-Calais ferry, I drive past Auguste Rodin’s famous copper sculpture Les Monument aux Bourgeois de Calais, located in front of Calais’s l’Hôtel de Ville (city hall). This article about the Hundred Years’ War and the Siege of Calais is inspired by that Auguste Rodin’s The Six Burghers of Calais sculpture.

The Hundred Years’ War:

My nephew and godson C in Dublin, is currently finishing his Leaving Certificate examination History coursework on the Hundred Years’ War, focussing specifically on the Battle of Crécy.

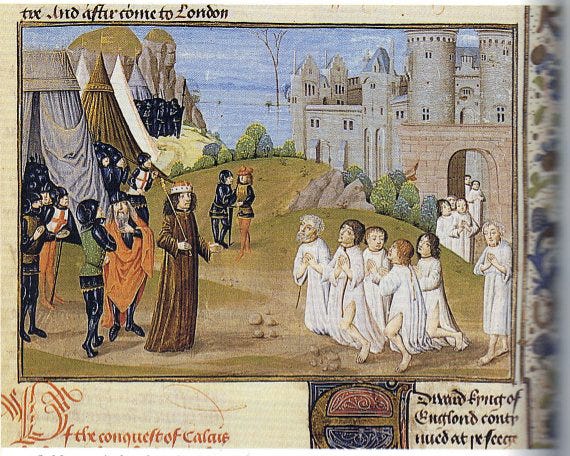

The Battle of Crécy, from a 15th-century illuminated manuscript of Jean Froissart’s Chronicles

I asked my nephew to summarise what he had researched and learnt about the cause of the Hundred Years’ War. This is what he shared with me:

The Battle of Crécy, won by King Edward III and his son, Edward the Black Prince, on August 26 1346 CE, was, alongside the respective battles of Poitiers (September 19 1356 CE) and Agincourt (October 25 1415 CE), one of the unlikeliest and most crushing English victories over their French nemeses during that 116 year period of sporadic yet brutal warfare that is known as the Hundred Years’ War…”

…The Hundred Years’ War was a century long conflict between the Royals and noble houses of England and France that began with the death of a king, the widowing of a pregnant queen and the birth of a princess in the year 1328 CE…”

…The dead king was Charles IV, the last Capetian (hailing from the aristocratic house of Capet) monarch of France…”

…King Charles’ death and Princess Blanche’s birth caused a great stir due to Charles’ failure to produce a male heir. Only a previous monarch’s male offspring/relation and their respective male descendants could stake a legitimate claim to the French throne due to the Salic Law of Succession. All four of Charles’ children from his two previous marriages had perished before reaching adulthood, and at the time of his death, his wife and queen Jeanne had yet to bear him a son…”

…Who then would be next anointed in Reims? It was that very dilemma which sparked the Hundred Years’ War.”

Shortly before his death, Charles had nominated his first cousin Philip of Valois as regent until the matter of Jeanne’s pregnancy was resolved (i.e., until the sex of the child was determined). Philip was the eldest son of Charles of Valois, who had been the younger brother of King Philip IV and hence the paternal uncle (and close confidante) of Charles IV…”

…It is possible that Charles was conscious that he may well be selecting his successor as King of France when he nominated his cousin Philip as regent.”

And indeed, after Charles’ widow Jeanne gave birth to a healthy infant girl on April 1 1328 CE, Philip quickly moved to have himself coronated. An assembly of notables was convened soon after, and the cases of the three contenders for the French throne were thrashed out.”

The first of the three contenders was Philip of Evreux, the eldest son and heir of Louis of Evreux. Louis had been a younger child of King Philip III and hence a half brother of King Philip IV (the father of Louis X, Philip V, Charles IV and their sister Isabella). Philip of Evreux’s claim to the throne was that he was the paternal grandson of King Philip III. Although unsuccessful in his bid for the French throne, he did succeed Charles as the King of Navarre.”

The second contender for the kingship was Edward III of England (he had been crowned King of England at Westminster Abbey at the young age of fourteen, a little over a year before his uncle Charles’ death, on February 1 1327 CE). Edward’s claim to the French throne was, that as Charles’ nephew via his younger sister Isabella, he was Charles’ closest male heir. Unfortunately, little is known of the arguments deployed by Edward’s proctors at that assembly of notables, but what we do know is that Edward’s claim was dismissed, purportedly because his claim to their throne was maternal rather than paternal in nature.”

The third (and ultimately the successful) contender for the French throne was Philip of Valois, who had been appointed regent by Charles himself shortly before his death. Philip was the eldest son of Charles of Valois and hence another paternal grandson of King Philip III. Charles’ appointment of Philip of Valois as regent no doubt added weight to Philip’s claim to the throne, but Philip was also the eldest of the three claimants (he was thirteen and nineteen years older than Philip and Edward respectively). France was in need of stability, and Philip, with his sizeable power base and widespread support, was best positioned to provide the kingdom with just that.”

The assembly soon promulgated their decision that Philip, then the count of Valois, was to be crowned the next king of France. And, despite vehement protestations from the young King Edward, who threatened to defend and uphold ‘our rights and our inheritances’ by all and any means necessary, Philip of Valois was crowned King Philip VI of France at Reims on May 29 1328 CE. However, despite Edward holding the title of Duke of Gascony (a wine-producing south-western French duchy) as a vassal of the French Crown, he did not immediately pay homage to King Philip VI upon his ascent to the kingship. It was only after Philip decisively defeated Anglo-aligned Flemish rebel forces at the Battle of Cassel (August 1328 CE) that Edward conceded, withdrew his claim to the French throne and finally paid simple homage to Philip VI at Amiens on June 6 1329 CE.”

However, in 1337, the French King Philip VI confiscated most of the remaining English territory in France. The English King Edward III didn’t accept this and declared himself the rightful king of all of France because he was the nephew of the previous French king.

In 1346, King Edward III invaded France, marking the start of the fighting in the Hundred Years’ War.

King Edward III’s forces marched into Normandy but were weakened by an outbreak of the plague.

After avoiding a pitched battle with French forces, the English were then trapped on the banks of the river Maye by a French army, which outnumbered them by at least three to one.

The English army’s archers used the longbow, which gave the English an advantage. The longbow was powerful and could sometimes kill armoured knights and their horses.

The Battle of Crécy was a significant loss for the French. The English army positioned itself at the top of a hill, and the French tried to ride up the slope to reach them. The long climb up the wet ground slowed the French horses down, giving the English archers and foot soldiers many opportunities to cause significant damage to the French.

The Siege of Calais:

The Siege of Calais, during the Hundred Years’ War, began on September 4 1346 and finished on August 3 1347. After his victory at the Battle of Crécy in August 1346, King Edward III marched north and besieged Calais, the closest port to England and directly opposite Dover, where the English Channel is narrowest.

After Edward landed in France in the summer of 1346, he sent his fleet home. He therefore now needed a secure port from which he could receive fresh supplies and reinforcements.

Calais was the perfect solution. It was very close to the English Cinque Ports (originally Sandwich, Dover, Hythe, New Romney and Hastings - but other towns in Kent and Sussex were added, including Faversham, where I have lived for 30 + years) and Flemish trade cities

such as Antwerp, that were then allied with England and could easily resupply Edward’s troops. Calais was surrounded by walls and a double moat and contained a moated citadel. Calais’s position on the English Channel meant that, once captured, the city could be supplied and defended by English ships easily.

Edward’s army of approximately 34,000 men was unable to penetrate the city’s defences. He also had twenty cannons, but despite many attempts, these made no impression on the city’s walls.

Initially, a stalemate reigned as the French failed to intercept the English lines of supply and the English failed to stop French sailors bringing in new supplies.

However, by February 1347, Edward III managed to prevent supplies from getting into Calais by sea and dug in for a long siege, starving the 8,000 citizens into surrender. Supplies of fresh water and food were reduced to almost nothing.

The surrender of Calais was signalled on 1 August 1347, but to spare the city’s inhabitants, Edward III insisted on the sacrifice of six of the city’s leaders. As portrayed in Auguste Rodin’s world famous sculpture, the six emaciated burghers: Eustache de Saint Pierre, Pierre de Wissant, Jacques de Wissant, Jean de Fiennes, Andrieu d’Andres and Jean d’Aire, with bare heads and feet, ropes around their necks and the keys of the town and castle in their hands, offered themselves to the English king so that their fellow citizens might live.

Subsequently, Calais remained under English control for two further centuries.

The Siege of Calais and the Arts:

The Siege of Calais and the sacrifice of the six Burghers of Calais have been the focus of an opera, several paintings, and, of course, Rodin’s renowned sculpture.

Opera and the Burghers of Calais:

L’Assedio di Calais (The Siege of Calais) is an 1836 opera, originally in three acts by Gaetano Donizetti, his 49th opera. The opera premiered on 19 November 1836 at the Teatro San Carlo in Naples, Italy.

The opera plot begins in 1347, when Calais is besieged by an English army led by Edward III. The people of Calais are close to starvation.

Photo: ETO; The citizens of Calais consider their fate during the siege, © Richard Hubert Smith

Aurelio, Eustachio’s son, raiding the English camp to get supplies, just manages to escape home.

A movement arises to depose Eustachio, the Mayor of Calais, but it collapses when he offers himself up to the rebels. The ringleader is revealed to be an English spy.

Eleonora, Aurelio’s wife, prays for the city’s safety. Aurelio wakes and tells her of a nightmare he had in which he died of wounds, as their son was also being killed.

Notice comes of a proposal from Edward, and the leaders of Calais assemble to discuss it. The offer is that in exchange for a universal pardon, six leading citizens should offer themselves up for execution.

Photo: ETO; The six burghers get ready to go for execution, © Richard Hubert Smith

Initial reaction is one of horror, and the citizens would prefer death in battle. However, Eustachio, in volunteering to be a victim, persuades them that the proposal is the only way to save the women and children. The five additional volunteers are quickly found, though Eustachio’s reaction to his son’s inclusion is mixed. The six Burghers of Calais prepare for departure.

In the English camp, Edward enthusiastically greets his envoy’s return, in the belief that he will finally be King of England, Scotland and France. His Queen (Philippa) arrives, having won a battle against the Scots. The six sacrificial victims enter, and a brief altercation ensues between Edward and Eustachio, who hands over the keys of the city of Calais.

The townspeople now come to beg for a pardon for the six Burghers of Calais, but Edward refuses. When the hostages ask to be taken to their execution immediately, Queen Philippa is moved by their courage and begs for a general pardon. Edward at last accedes, and there is universal celebration at the King’s clemency and the forthcoming peace.

By 1840, the opera had disappeared from the world’s stages, and it did not reappear until 1990 at the Donizetti Festival in Bergamo, Lombardy, Italy, where Donizetti was born.

In modern times, the opera has been revived and has been performed at the Wexford Festival Opera in Ireland in October 1991 and by RSAMD (now the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland) at the New Athenaeum Theatre, Glasgow, on 27 June 1998. The opera received its first U.S. professional staging at the Glimmerglass Festival in 2017, performed at the Alice Busch Opera Theatre on Otsego Lake, eight miles north of Cooperstown, New York State.

Video: YouTube, The Siege of Calais (L’Assedio di Calais), Donizetti, English Touring Opera, 2013

The 2013 English Touring Opera production was the first professional performance of Donizetti’s The Siege of Calais in Britain. English Touring Opera listed the production team as follows:

Eustachio, Mayor of Calais - Eddie Wade

Aurelio, Eustachio’s son - Helen Sherman

Eleonora, Aurelio’s wife - Paula Sides

Edoardo III, King of England - Cozmin Sime

Pietro de Wisants, burgher - Brendan Collins

Giovanni d’Aire, burgher - Andrew Glover

Edmundo, English general - Adam Tunnicliffe

Giacomo de Wisants, burgher - Niel Joubert

Armando - Matthew Sprange

Incognito - Piotr Lempa

Conductor - Jeremy Silver

Director - James Conway

Designer - Samal Blak

Lighting Designer - Ace McCarron

Rupert Christiansen in the Daily Telegraph newspaper (March 11, 2013 ) gave it 4 stars and, while having some reservations about the loss of the third act and the modern setting, praised both singers and orchestra, ending with “Robust, virile and emotionally charged, this is yet another Donizetti opera which proves those upturned noses [of the cognoscenti] unjustified”.

Paintings and the Burghers of Calais:

The Burghers of Calais, (1346), from a 15th-century illuminated manuscript of Jean Froissart’s Chronicles.

Anon: The Burghers of Calais, 1400s

Jean-Simon Berthélemy: Les Bourgeois de Calais (1782), Musée des Beaux-Arts, Béziers exhibited 1967, photo: Sotheby’s, Paris, 21 June 2012, lot 66

It is worth noting that Edward III’s queen, Philippa of Hainault and niece of the French king, Philip VI (seen in the paintings above and below), was born in Valenciennes, in the Pas de Calais region, so the six Burghers of Calais were her compatriots.

Benjamin West: Queen Philippa Interceding for the Lives of the Burghers of Calais (1788), Detroit Institute of Art

Ary Scheffer: Le Dévouement patriotique des six bourgeois de Calais (1819), Musée du Louvre, Département des Peintures, On long-term loan to the Assemblée National, Paris

Sculpture and the Burghers of Calais:

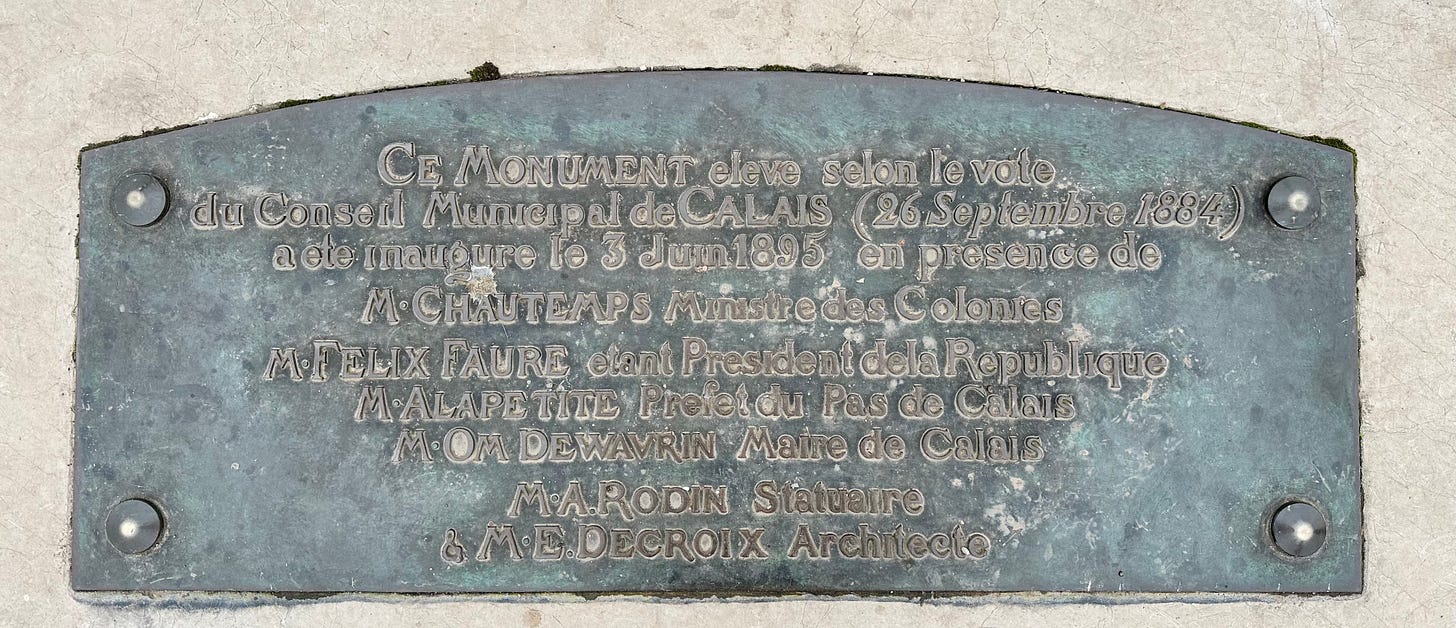

Auguste Rodin (1840 - 1917) was commissioned to create this bronze monument in 1884 by the city of Calais, to honour the collective sacrifice of the six burghers, who went to hand over the keys of the city to the victorious King Edward III at the end of the 1346 - 47 Siege of Calais, during the Hundred Years’ War.

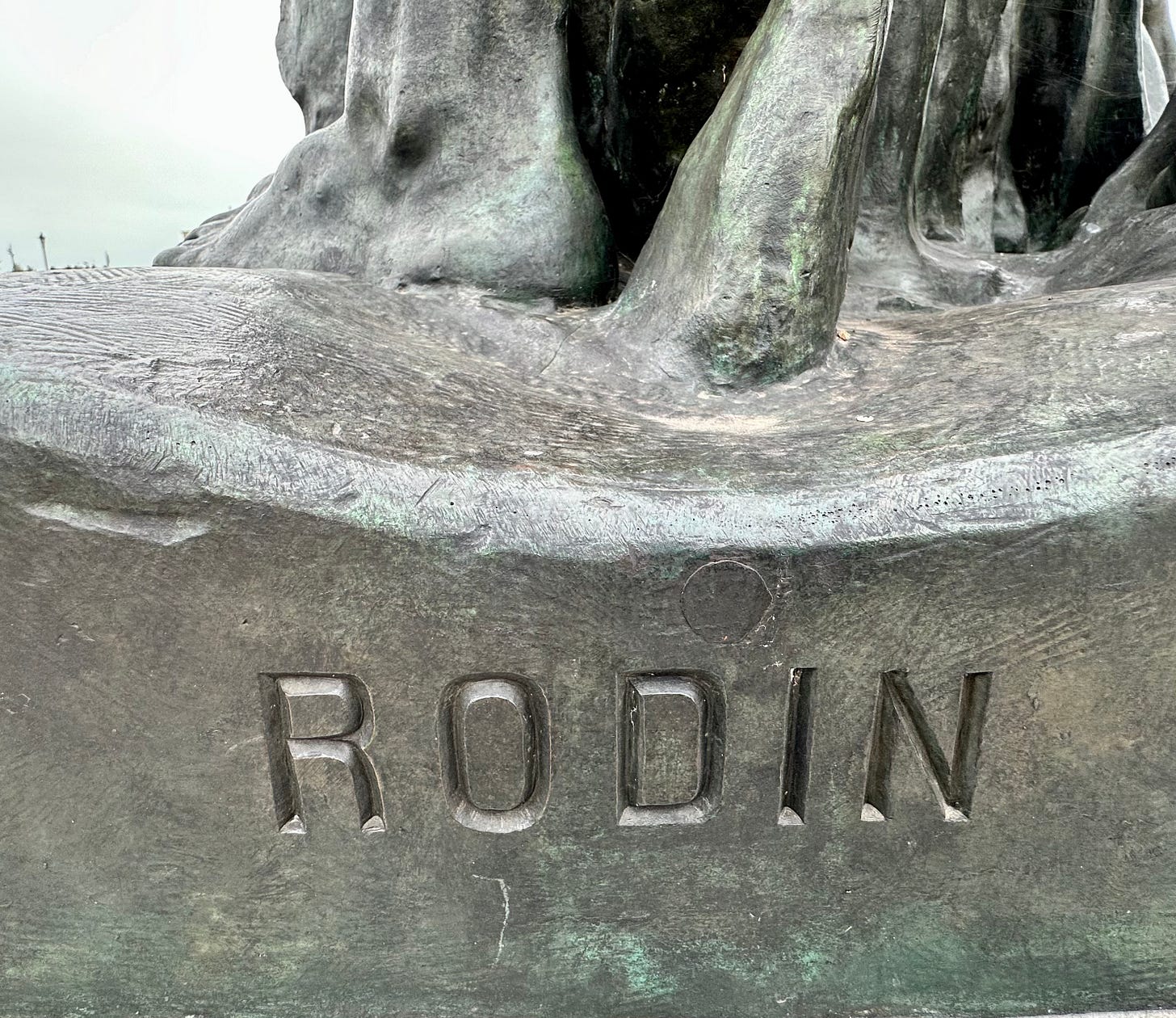

Photo: author

The six characters are individualised, united on the same base, but independent. Alone facing their destiny and death, they do not look at each other, they do not touch. Simply dressed in sackcloth tunics, with a rope halter around their necks and bare feet, the condemned men begin their slow funeral march. Rodin’s sculpture emphasises the internal struggle of each man as he walks toward his fate.

Photo: author

Rodin gives each figure a specific gesture and movement - from despair to abandonment, from confidence to resignation.

The sculpture, completed in 1889, was installed in 1895 in the town hall square in Calais. Rodin was not pleased with the original display of the Calais sculpture group as it was erected on a tall pedestal, enclosed by an iron fence, rather than on a low base in front of the town hall. Eventually, it was installed as he wished in 1924, seven years after Rodin died - on the ground, “right on the flagstones of the square, like a living string of suffering and sacrifice” (Rodin).

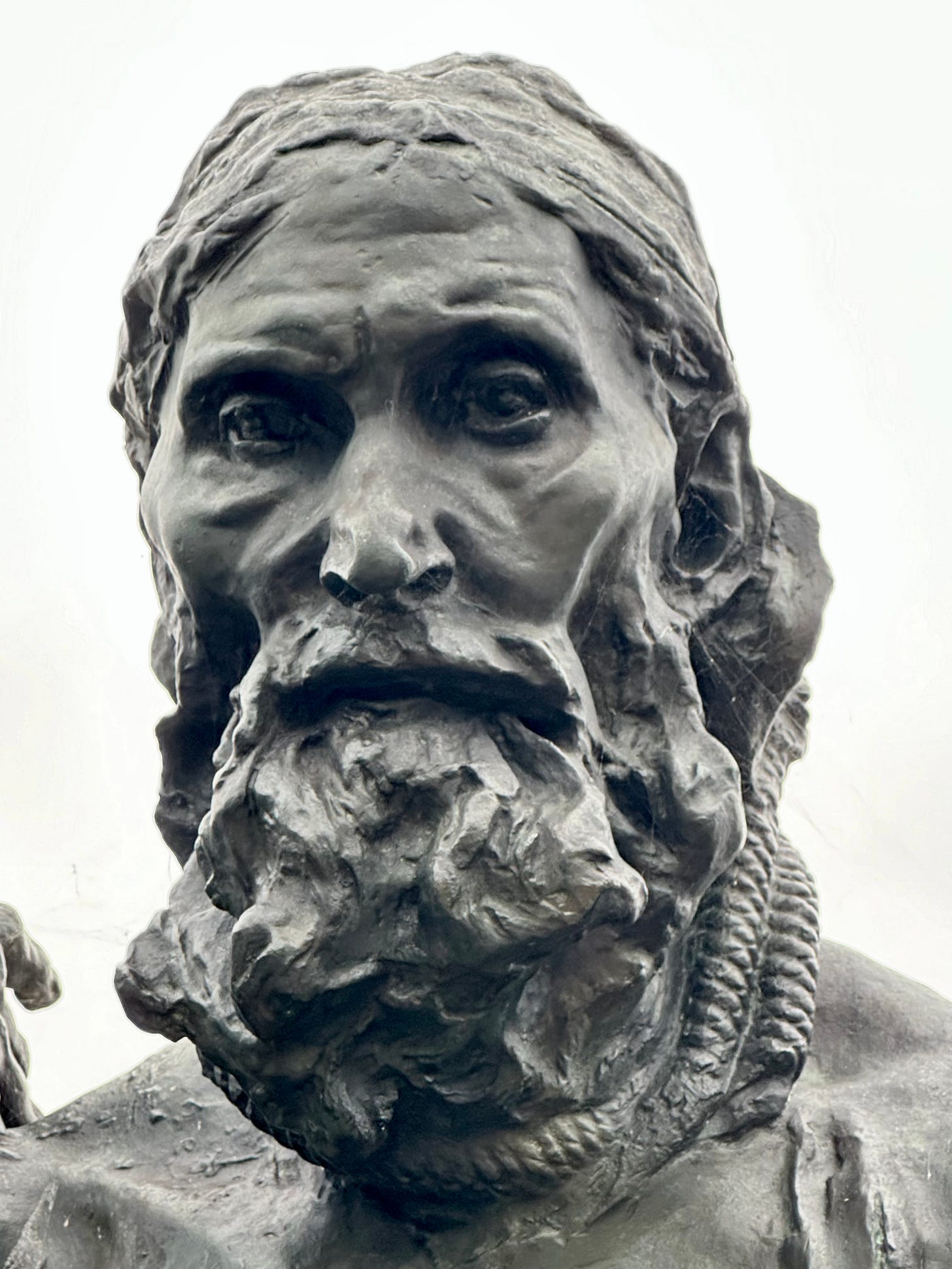

Eustache de Saint Pierre:

Photos author: Eustache de Saint Pierre.

Eustache de Saint Pierre was the first of the six bourgeois to have agreed to sacrifice himself to save the inhabitants of the city of Calais. The oldest of the group, he has a beard and a moustache, wearing a shirt and a rope around his neck.

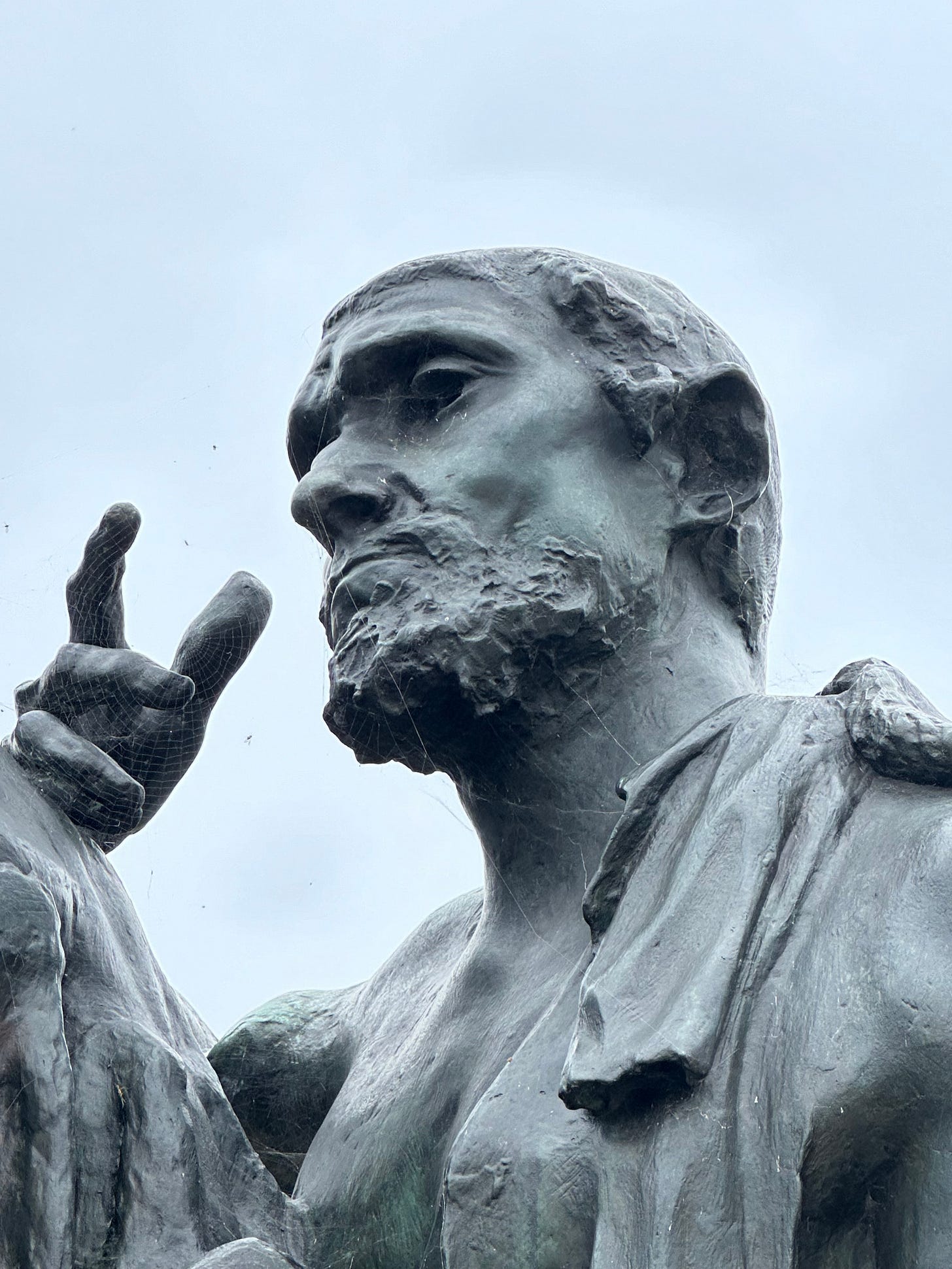

Pierre de Wissant:

Photos author: Pierre de Wissant

Pierre de Wissant, the younger brother of Jacques and the second youngest of the six burghers, his body and face still turned backwards, takes the first step towards sacrifice. He was the third Burgher to volunteer. Note the character of the straining tendons of his elongated neck, perhaps echoing Pierre’s highly emotional contemplation of the idea of his own death.

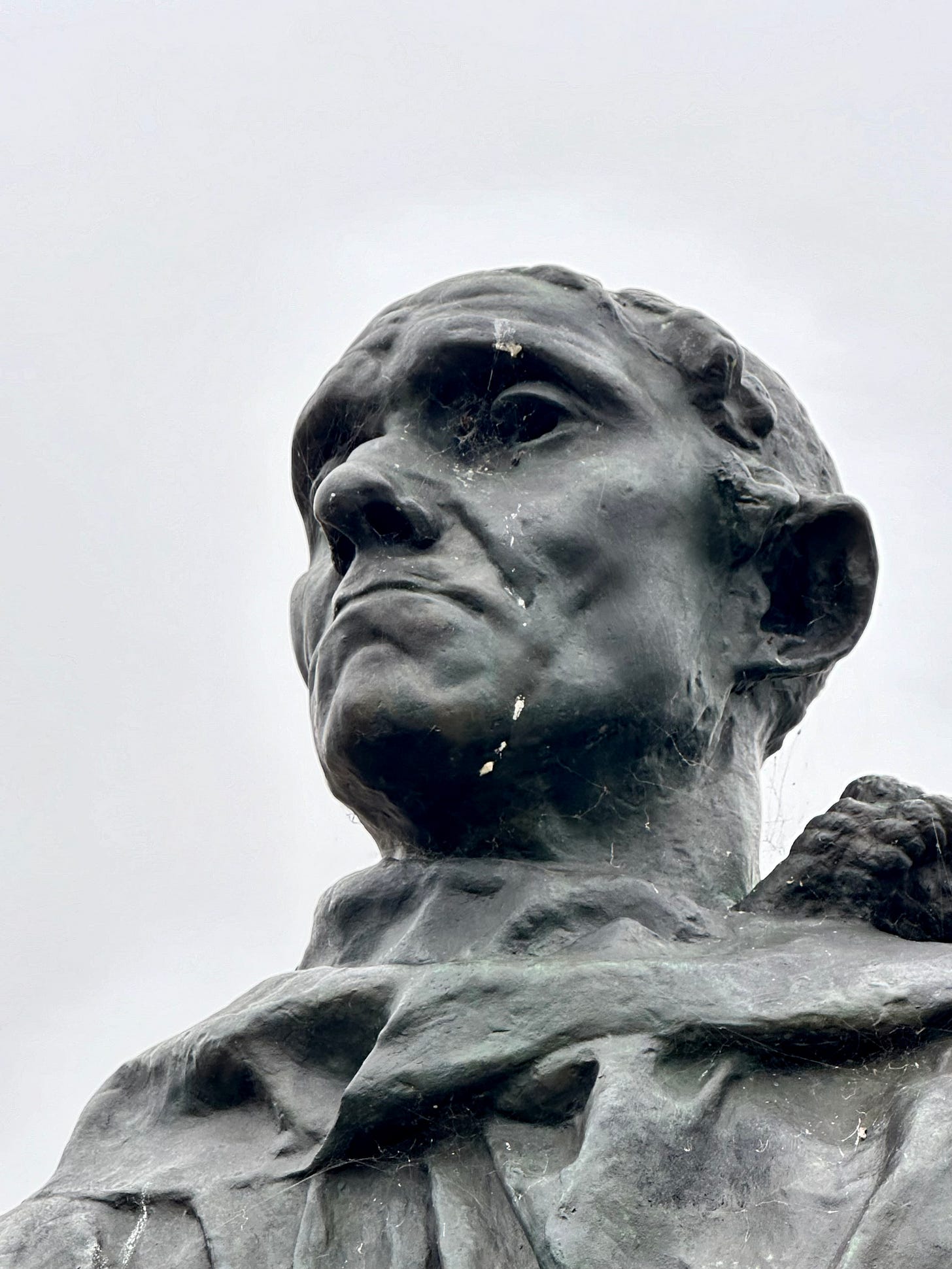

Jacques de Wissant:

Photos author: Jacques de Wissant

Jacques de Wissant, the older brother of Pierre, walks resolutely.

Jean de Fiennes:

Photos author: Jean de Fiennes

Jean de Fiennes is the youngest of the six burghers. His mouth is open and his arms are outstretched, as he looks back towards Calais. He departs to his uncertain fate, as if he were questioning his decision to sacrifice himself for the safety of the people of Calais.

Andrieu d’Andres:

Photos author: Andrieu d’Andres

With his head between his arms, Andrieu d’Andres seems frozen in an attitude of complete despair.

Jean d’Aire:

Photos author: Jean d’Aire

With his head held high, Jean d’Aire looks straight ahead with a defiant attitude. His eyes betray sadness, yet his firmly turned-down mouth and forceful jaw expose an angry strength. He was the second burgher to volunteer, after Eustache de St. Pierre. Jean d’Aire holds the keys of Calais, a burden all the heavier as it is the shameful sign of surrender. According to the medieval writer Jean Froissart, he was a “greatly respected and wealthy citizen, who had two beautiful daughters”.

Reflections:

Relations between close neighbours England and France have been complex and sometimes fraught down through the centuries. The Hundred Years’ War and Brexit, for example. Yet, sometimes during times of global strife and difficulties, such as World War II and the current warfare in Ukraine, these two countries have shown that they can work together for the common good. We must not lose hope.

Photo: Andriy Yermak, BBC, Presidents Macron, Zelensky, Trump and Sir Keir Starmer at the Vatican, for Pope Francis’ funeral on Saturday 26/04/25

Thank you to my nephew and godson, C, for his valuable thoughts on the causes of the Hundred Years’ War. I do enjoy our chats and his lively writing on various topics.

Introducing Contributor, Caroline McCormick-Clarke

Immerse yourself in all of Caroline’s articles on her Contributor page.

I remember your original post about this, and I learned so much. I had no idea about the opera and found that especially interesting, among all of the other details.

I love this sculpture, and hadn’t realized that each individual was identifiable; nor that Donizetti had created an opera about their amazing act of collective selflessness. Thank you for such a fascinating and in-depth article.

Here they are at Compton Verney in 2014: https://pbase.com/homeward/2013_moore_rodin_03_calais