The Last Voice of Paris: Why Macron Honoured a Street Newspaper Hawker

“Ça y est!” — Paris beyond the clichés

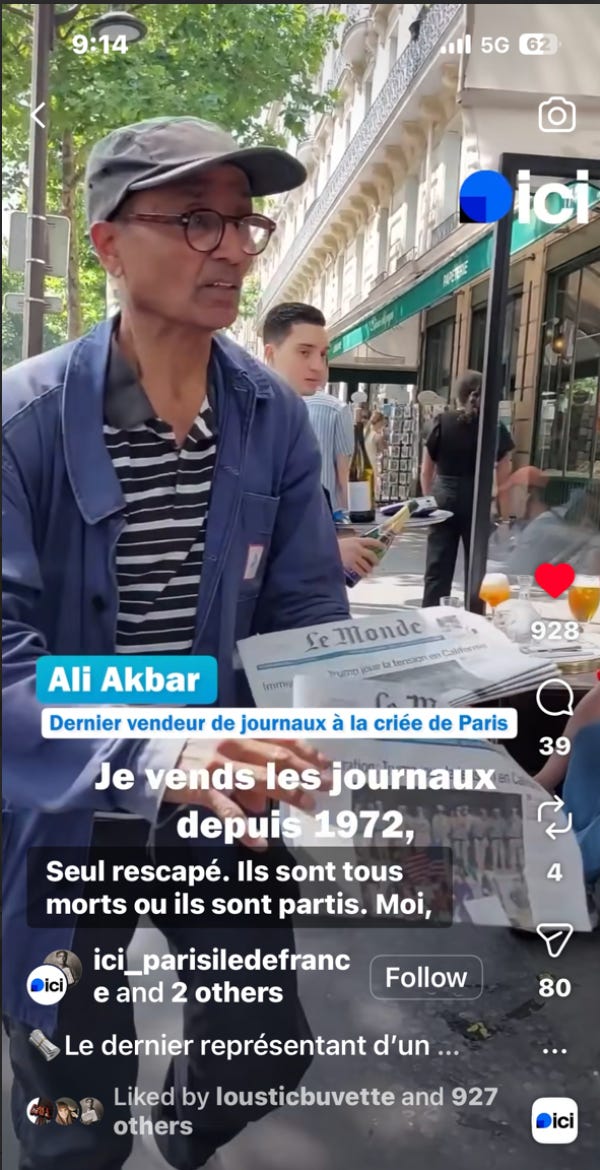

There’s a sound that’s been punctuating Parisian mornings since 1973. Not the clatter of café cups or the rumble of the Métro, but something far more human: the voice of Ali Akbar shouting “Ça y est!” as he hawks copies of Le Monde newspaper across the cobblestones of Saint-Germain-des-Prés.

On January 28, President Emmanuel Macron invited the 73-year-old Pakistan-born vendor to the Élysée Palace and pinned the National Order of Merit to his chest. It was a ceremony that revealed something profound about French democracy, and about what it means to serve your community for half a century without ever expecting anything in return.

“That’s it, I’m a knight! I’ve made it!” Ali declared afterwards, his joy radiating through every interview. But here’s the thing: Ali had already made it, years ago. He’d made it every single morning he turned up on those streets, rain or shine, bringing the news to a neighbourhood that’s watched him become as much a fixture as the literary cafés themselves.

Macron called him “the most French of the French” and “the voice of the French press.” Strong words for a man who doesn’t even hold French citizenship. But perhaps that’s precisely the point.

When Ali started selling newspapers in the 1970s, about 40 street hawkers were working in Paris. Now he’s the last one. The sole survivor of a tradition that once made news a physical, communal experience rather than something you scroll through alone on your phone at breakfast.

Think about what that means. For over 50 years, Ali has been democracy’s town crier. Not literally shouting headlines (though his “Ça y est!” certainly announced their arrival), but making the news accessible to anyone passing by. No algorithm deciding what you should read. No paywall. Just a man, some newspapers, and his voice carrying across the 6th arrondissement.

He started out selling Hara-Kiri and Charlie Hebdo before settling on Le Monde. That progression tells its own story about French press freedom, from satirical provocation to serious journalism, all distributed by the same dedicated hands.

The ceremony had another layer that made it even more touching. Macron was once Ali’s customer. Back when he was a student at Sciences Po, the future president would stop to buy his morning paper from this street vendor.

The student became the president.

The vendor became a knight.

Both men travelled their own 50-year journeys to meet again at the palace.

It’s a reversal of the usual power dynamics in French honours. The customer thanked his vendor. The palace acknowledged the street. The president remembered the man who served him Le Monde when he was nobody special.

You bring political news to our terraces at the top of your lungs,” Macron told him during the ceremony, acknowledging the cafés that have become Ali’s beat: Café de Flore, Les Deux Magots, Brasserie Lipp. Though Ali himself has noted, with typical frankness, that those famous spots have become too touristy for his taste these days.

These days Ali sells about 40 papers daily, down from 300 when he started. Digital media has done what you’d expect. But he keeps showing up anyway, because this is what he does. This is who he is.

The National Order of Merit can’t save his profession. There won’t be another generation of newspaper hawkers in Paris. When Ali eventually retires, that sound will disappear from Saint-Germain. “Ça y est!” will become a memory, then a story old-timers tell about how news used to arrive on the Left Bank.

But the honour does something else.

It recognises that some contributions to French culture can’t be measured in citizenship papers or profit margins. Sometimes being French is about showing up every day for 50 years, becoming the voice and the accent of your neighbourhood, and serving your community with such dedication that even the president remembers you.

Democracy isn’t just about voting or reading the news. It’s also about the rituals that bind us together. The daily exchanges. The familiar voices. The man on the street corner who’s been there so long he’s become part of the street itself.

Ça y est, Ali. You’ve made it. You always had.

À Bientôt

Judy

Sources

Official Presidential Source:

Élysée Palace Official Agenda: https://www.elysee.fr/agenda

French Media Coverage:

Further Reading

Background on Ali Akbar:

About the Honour:

Official French Government: https://www.france-phaleristique.com/ordre_merite.htm

Introducing Contributor, Judy MacMahon:

Visit her Contributor Page — Explore more of Judy’s work

MyFrenchLife™ – MaVieFrançaise® is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Nice story.

This piece is so beautiful Judy!

"It recognises that some contributions to French culture can’t be measured in citizenship papers or profit margins. Sometimes being French is about showing up every day for 50 years, becoming the voice and the accent of your neighbourhood, and serving your community with such dedication that even the president remembers you..."

This especially resonates with me as I could only hope to make as big of a contribution with my sacred work in this city...