Unspoken French Rules, from Cheese to the Bise

By Shelby Chambers: The first rule about French rules is you have to say there are no rules.

I frequently share the story of the first time I met my French in-laws back in 2015. It was at a cute little cottage in Brittany, wherein a fortuitous encounter with cheese led me to discover THE RULES. Not that they matter. But they do.

My in-laws weren’t my in-laws then; they were my boyfriend’s parents, and because I’d met that boyfriend in California, the French culture didn’t yet play a major role in our relationship. So far, everything in our relationship had been my way, the Californian way, the Los Angeles way, the anything-goes way. Eat dinner any time you want, in any order you want, maybe not at all. Talk over one another; the person with the best story wins. Say you’ll be at a party, then don’t go to the party. Scroll on your phone at your own dinner party. You know, normal rules. My boyfriend constantly told me how oddly I lived my life, and I dismissed him as just being grumpy or snobbish.

But then one day, he invited me to a wedding in France and then to meet his family on a quick trip to Brittany. I was nervous about meeting them: would they like me? Was being American a good or bad thing to them? How would we interact when they spoke no English and I spoke even less French? I hadn’t yet considered that I should be more nervous, since I didn’t know squat about the French rules that aren’t rules but are definitely rules. My boyfriend, maintaining that there were no rules and I should be myself, did not prep me for any rules, and therefore did not set me up for success.

I still don’t know how many faux pas I committed on that trip. I was tired, having been up until 5 am at a wedding the night before. I didn’t know French except to order wine and count to 100, so I sat silent at dinners that lasted over an hour. I know that I was on my phone way too much. I was still managing content strategy at Disney, so I was constantly checking email, the Disney blogs, and social media because one of the few American rules that isn’t a rule is that if you’re on PTO, everyone says not to check in, but you actually have to check in. If you don’t, you’re shamed. That probably didn’t look good to the future French family.

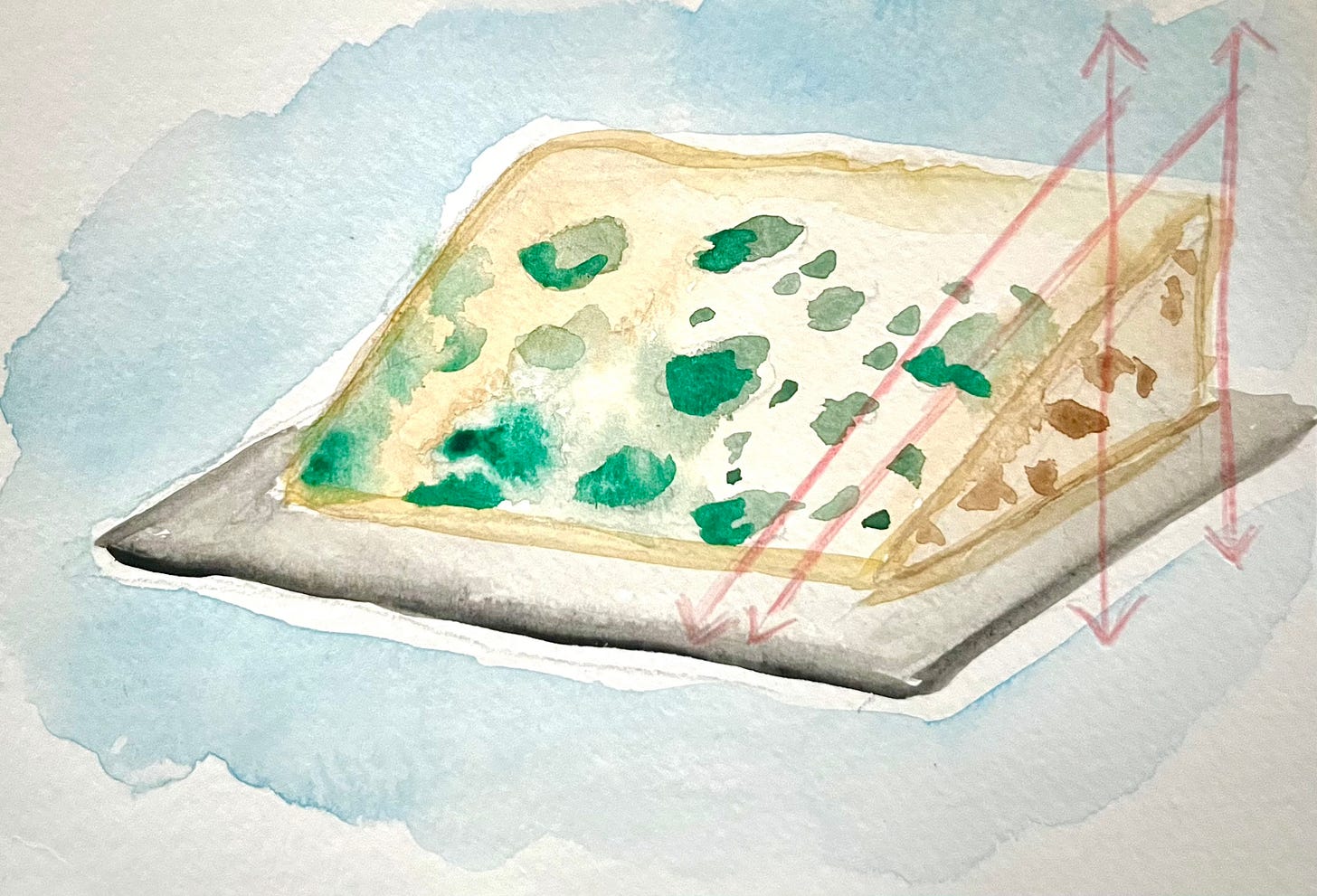

But the most critical thing that happened, the moment that unlocked the French culture for me and made me aware of an endless minefield that lay ahead, was when my boyfriend’s sister’s boyfriend (also new to the family) cut the Roquefort wrong.

You see, Roquefort is usually served in a wedge that lies on its side, and apparently, even though it’s not a rule, you are required to cut it into thin slivers that are all the same size. You can’t do an angular cut or cut just the skinny part off, because then everyone will get different thicknesses and textures of cheese, so apparently, it is known only to cut in this one way. The poor guy began to advance his knife to the cheese in preparation for a triangular cut, and my not-yet-father-in-law exclaimed, “No!” and showed him the correct way to literally cut the cheese. (Americans will laugh here, but there’s no other way to say it.)

I was mortified by association, and have never put a knife to cheese without hesitation since. When it was my turn to attempt, I hovered above a camembert for a few seconds, looking at my boyfriend’s father for instruction. He told me not to worry, there were no rules, to do as I please. Except for the Roquefort, that one had to be cut that way. I soon learned this also wasn’t true; other cheeses also had a correct way to be cut, and it usually wasn’t my way.

Slowly, I realized that there was a right way to do everything, and everyone knew the way except me. My French teacher had taught me to introduce myself, but not that I’d have to introduce myself to each and every person in a room, full introduction and bise, even if there were 40 people present. It seems like French class shouldn’t just teach conjugations too complex for me to understand even in English, but maybe also French customs, so that I could eventually exist in French situations.

Why didn’t someone tell me this stuff in advance? And why did they always say not to worry, it wasn’t a big deal, there weren’t any rules? Just to throw me off even more? I think it’s because in a high-context culture like that of France, all of the little ins and outs are self-evident to insiders, so they don’t see that there is anything particular to heed. Entering this high-context culture as naive and enthusiastic Americans, we traipse all over the rules without realizing they might exist, or that they matter. Ask any French person about the rules, and they will first say, “Oh no, there aren’t any rules, don’t worry about it!” Then point out a few rules and they will say, “Oh yeah, I guess you’re right, there are. I hadn’t realized that before.” It would be quite a beautiful dynamic if the not-rules rules didn’t leave me embarrassed so often.

Anyway, enough context, let’s get to the rules! Keep in mind, these rules aren’t absolute. They change by family, by region, by generation. These are more like guardrails of rules categories to look out for in your next French encounter. Know which categories tend to be regulated (frequently “greetings” and “cutting things”), then stay alert to note what the rule actually is.

*Quick Author’s Note: My poor father-in-law is mortified by the cheese story, especially because I bring it up often (every time we eat cheese). So, in case he’s translating this to French to read it: it’s all in good fun, and look, this funny interaction gave me the idea for an entire post!

The Cheese

Let’s close out the cheese rule, briefly. Not every family has a rule about Roquefort, nor are there absolute rules about how to cut every cheese. But I do know that every time my American copines and I share a cheese board, we all hesitate, then ask each other if we’ve been told by a French person how to cut this or that cheese. We have enough stories of being instructed to know there’s a way to do each one, no matter how many times we’ve also been told it doesn’t matter.

I’d advise sticking to rectangular-shaped cheeses if you have to cut first, then doing a straight-across cut until you get toward the end, where this becomes difficult. Then it’s usually allowed to begin angular cuts until the cheese is gone. Circular cheeses are pretty self-evident as well: pie away each part. When in doubt, wait for a French person to cut first.

I’ve always fantasized about approaching a large slab of Comte or Cantal and cutting a chunk right out of the center, just to see the effect on the dinner party. Maybe once I’ve received my French citizenship, I’ll attempt it and tell everyone there’s a new cheese rule in town.

The Bread

This rule I was told when I asked my French family for help identifying more French cultural rules, so, straight from the source. They let me know that some families allow tearing the bread at the table, others require the bread to be cut in the kitchen and brought in via a basket. This rule is less treacherous, as you are usually served the bread and can infer the rule based on what your host does.

Just make sure you’re not assigned the bread-cutting task at a dinner party, should you be brave enough to offer the host a hand. Some families prefer bread cut into small rounds, like how it’s served at restaurants, while others like pieces sliced down the middle, usually a cut reserved for breakfast. Some families do one slicing style for breakfast, a different one for lunch, and dinner, so keep your eyes peeled for indicators. You could also just ask how they’d prefer the bread to be cut, but A. who is brave enough to do that, and B. they will tell you it doesn’t matter when in fact, it really and truly does.

The Conversation

There is nothing in French culture that is more important than the current conversation. Is it 1:30 am after a long dinner, and you’re about to miss the last metro? Doesn’t matter; we all have to close out the current conversation. Is there a long line at the supermarché with only one register open? Doesn’t matter, the customer and clerk have to have as full a conversation as needed to be polite. You’re starving, and a delicious plate of food is cooling before you as one person at the table recounts the entire plot of the Iliad? Don’t even look at your food; the conversation is all that matters.

I’ve spoken with French friends about this one, and they all complain about how they hate waiting to start eating, or they hate when people stand on the sidewalk having long conversations, forcing foot traffic to go around. But even as they don’t like the effect of the conversation, none of them is capable of denying the conversation its importance. They all carry on with rapt attention as I sidle closer to the door at the end of a dinner party. They all respectfully listen to a friend’s tale as their food grows cold. While I struggle with this rule, especially when I’m hungry or tired, I suppose I do respect it.

The Bise

I’m very curious to see if the bise disappears with Gen Z, too globalized and TikTok’d to carry on such an old-fashioned salutation. But then, the pandemic only paused it for a few months, then everyone was back on the bise wagon even before mask mandates ended, so maybe the double kiss has staying power.

I can’t explain how the bise works; you just have to let it happen naturally. The more you think, the more you’ll mess it up; you’ll lean in for the wrong side, you’ll miscalculate your speed, and knock heads. All you have to do is get close enough to the orbit of the French person and give in to their gravitational pull. They’ll have a preference for left or right; I don’t know how to read this, all I know is that by now, my body intuits the signs and then falls in line. If I keep my brain as empty as possible, I can achieve both kisses at the perfect distance from their face; not too close as to be a real kiss, but not so far away as to seem like I’m afraid of kissing them, even though I am.

None of that has anything to do with a bise-related rule. Those are just the ramblings of an overthinker who has been made to kiss a lot of people I never planned to kiss. No, the rule about the bise is that you have to do it to everyone present. Upon entering and exiting. Fully committed, no flinching, even if you don’t like them, even if you didn’t interact with them in any other way that day. Smack, smack.

The Aggression

How did we go from the bise to aggression? Two sides of the same coin, no? Maybe true when it comes to customer service.

As a fake and overly friendly American (apparently), I usually think that kindness and my winning smile will earn me good customer service. If you live in France, you’re cackling because you know nothing pisses off a cashier or La Poste employee more than you being nice to them. Sometime very recently, I realized that aggression in the service domain is expected, nay, required on both sides.

When I had that awful run-in during my citizenship interview, I went into fawn mode, something I haven’t done in years, but I was so shaken up, my nervous system thought fawning would be a good route. This seemed to only make matters worse. A friend pointed out that I should have met the woman where she was and been just as unkind, blunt, and rude as she was, then maybe she would have expected me. My mind was absolutely blown. My friend was right. I should have matched her in tone and disdain. I should have asked her to stop interrupting me. I should have asked her to clarify her many questions that weren’t questions. We might have parted as friends.

Hadn’t I seen this at the post office before? A worker says a package isn’t there without even checking. The customer says it’s not possible, they both volley digs and daggers back and forth, unsmiling, until the package is finally found. In the process of scanning, one of them folds and says something kind to the other, now that they’ve both proven themselves to be worthy adversaries. Maybe it’s a comment on the weather or the faulty system that actually means “okay, we’re fine now, you and I.” They part with a “bonne journée” as if neither had been rude or aggressive in any way. Aggression is the table stakes for the game of service; my dumb smile isn’t any good here.

The Bon App

You absolutely cannot begin your meal until someone says “bon app.” There’s a force field around your food until those magic words are spoken. Alternatively, you or someone else at the table can act like you just remembered you have food in front of you and say “oh, well, we should eat, shouldn’t we?” then perform that you’re reluctantly going to begin dinner even though you’ve been dying for minutes to dig in.

I’ve actually internalized this rule and feel an ungracious level of disdain for anyone who begins to eat before everyone is seated or before everyone has put off eating as long as possible. My poor parents even get a chiding from me when they visit and begin to chew before we’ve done the performative putting off of the meal for several minutes. Sorry, parents.

The Produce

My brother-in-law just asked me while we were eating peaches if it was time for peaches already. I told him not to ask me, I’m not French; anytime I’m eating a peach, it’s time to eat peaches. But I loved this interaction, the way that he asked me, as if the season were some kind of cultural secret that is shared in a clandestine way that only other French people can see; a cloaked signal that lets us know that we’re allowed to start enjoying tomatoes again.

The thing is, that’s kind of how it happens. One does not eat a vegetable out of season here in France, and even if it can be found at the marché, one does not buy it until it is in season. If you do enjoy a piece of produce out of season, it is required that you state that it’s still too early, and that the fruit or vegetable was “pas terrible.”

Okay, so how are we all supposed to know when something is “in season” if the mere presence of the produce at the marché is not evidence enough? You follow the Mamies. Having too often purchased produce that was available at the marché, only to be told by my husband that it was “too soon,” I’ve offloaded that executive decision to the French grandmothers at the marché. If they are buying strawberries, then it must now be strawberry season. If they aren’t buying the strawberries, it must still be too soon. Or I just make my husband do the shopping because hell if I’m going to take the time to head to the marché and lug back a haul only to be told I bought the wrong thing (again).

The Salutation

I’ve spoken here before about the importance of saying “bonjour” at the beginning of any interaction in France, something I had a very hard time doing because “bonjour” is a word that immediately gives away that you’re American. We are not good at saying that word. For years, I sounded like Emily in Paris (“BONE-DDDJOOOOOR!”) every time I uttered hello, until I took pains to practice how to shape my mouth to sound more French, and then repeated it over and over enough times to fly under the radar. I also hated the idea of saying hello to every elevator or waiting room that I entered, even if I wasn’t going to interact with those people. Probably looked pretty rude at many a dentist RDV.

But anyway, you gotta do it or potentially face denied service as Pamela Clapp describes in her recent post, “No Greeting, No Help.”

In a twist of irony, while brainstorming these rules en famille, my Sister in law pointed out to me that we have the same convention in America. “No way!” I said, not remembering saying hello to a shop owner or employee a single time in my life. “Yes!” she countered, “and then they’ll ask how you’re doing even though no one actually wants to know how you’re doing.” She was right. The correct response to “how’re you doing?” is “good thanks, how’re you doing?” even if you’re on fire or bleeding out, and then end of conversation.

You don’t actually know the rules that you know. America has them too, I just can’t see them.

And so…

The point is that the rules aren’t grave, nor are they sinister in most cases. You can break them and won’t be outcast from society (for long). The rules are also quite family and region-specific, so they will change from house to house. The best thing to remember is that they are there, and you should keep an eye out for them lest you want to feel weird or have bad attention drawn to yourself

Also, there’s nothing wrong with having rules. We have them in America, too, but we also have more variety in general, which makes the rules more elastic and invisible. If someone has a different rule, it’s easier for us to say, “That must be how they do it in that person’s state.” Some houses are shoe-free, others are pro-shoe. Some people cut with the knife in the right hand, then switch; some people eat with their fingers despite their parents trying for decades to make them stop.

But France has all the rules yet much less flexibility, so the best way to get the best service and the fewest glances is to learn them, integrate them, or at least do an ocular pat-down of the situation before you cut the cheese.

Introducing Contributor, Selby Chambers

Immerse yourself in all of Selby’s articles on her Contributor page.

A fun and on-target post from @Shelby Chambers about some subtle rules of French life that may or may not be real rules...

One "rule" that is not really a rule that I've noticed, and drives me crazy to this day, is that at the end of what has already been a long dinner party, when the first person says "Il est déjà 1 heure? On y va, chéri?" (It's already one in the morning? Shall we get going, hon?) this in no way means anyone is going to get going.

It's usually just a first indicator that maybe people are going to start to think that the evening will eventually come to an end, which will eventually mean leaving. The time between the first "on y va?" and the actual "on y va-ing" is often about an hour, but I'd say more usually at least half an hour. I pointed this out to my French friends once and they had never really noticed it, although they agreed it was true.

Oh Shelby. This is hilarious. I wavered between your confidence and mmmm having been admonished for not knowing the rules that are not really rules are they??? Every word ring the bell of truth and real life in France. Thanks for sharing.

Judy