Jean Moulin: France’s hero? Unravelling fact from fiction

‘Jean Moulin’ is the third most popular name for a French école primaire, collège or lycée. A university in Lyon is named after him. And a short stroll around any populated area in France will undoubtedly reveal a rue, place or boulevard Jean Moulin.

But just who was he, this most honoured of maquisards? A true hero of the French Resistance? Or was his story exploited and appropriated by others for political gain?

Charles de Gaulle and the post-war mythology

As with all countries, the history of France is built on fact, myth and legend. As with all countries, some facts can be uncomfortable. And, as with all countries, even historical facts can be camouflaged, manipulated and modified with the skilful construction of myth and legend.

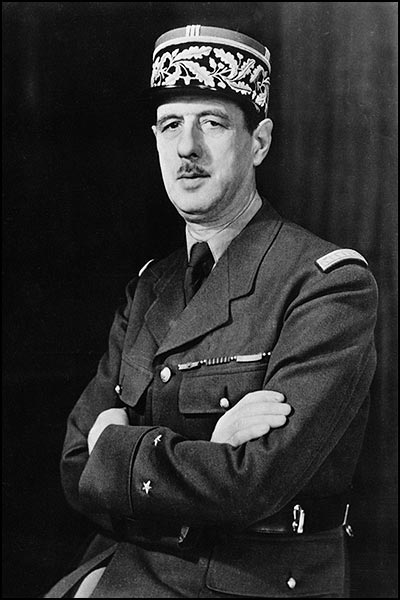

After WWII, De Gaulle was determined that certain awkward wartime details would be massaged for the sake of national pride.

He worked assiduously to promote his particular version of events. Collaboration with the Nazis was top of his list to be overlooked, closely followed by the story of the liberation.

His strategy worked. France liberating herself almost single-handedly and being united against the Nazi occupation and Vichy government is still believed to be fact by many French people.

Jean Moulin: an iconic figure

Back to Jean Moulin. Universally perceived to be the classic hero

of the French Resistance, he is recognised by practically everyone in France thanks to the famous monochrome photograph of him wearing a scarf and fedora.

In 1943, he was in London. On General de Gaulle’s orders, he was parachuted back into France on a crucial mission; to unify and secure central control over the very fragmented resistance organisations. He succeeded admirably by forming the Conseil National de la Résistance.

Due to notoriously bad security practices, Moulin was soon betrayed and arrested. He was tortured by the head of the SS, Klaus Barbie, and is believed to have died on a train headed for Germany.

A new era of politics

Fast forward to 1965. The forthcoming elections were top of General de Gaulle’s mind. He had recently told the Algerian pied-noirs, “Je vous ai compris.” But this didn’t mean that he sympathised with them. And the public soon decided that his policy of granting Algeria independence was a sell-out.

By the autumn, his ratings were on the skids, declining from a comfortable overall majority to only 44%.

Something was required to remind France about the victories and glories of the past. Showing great political skill, de Gaulle had Moulin’s remains transferred from Père Lachaise cemetery to the Panthéon.

This invoked powerful memories of Jean Moulin as the leader of l’armée des ombres, and Charles de Gaulle as the liberator of France.

However, historians are divided about Jean Moulin and many key questions remain unanswered:

- What was his role in the Spanish Civil War, and did he use his position in the French aviation ministry to surreptitiously deliver planes from the Soviets to the Spanish Republicans?

- Was his attempted suicide in German detention in Chartres genuine or a carefully contrived ruse?

- Why, when working for de Gaulle, did Moulin conceal his contacts with a circle of Soviet agents? Could he have been one of Stalin’s stooges in France?

Like many of the world’s great politicians, de Gaulle was a master of myth-making. So the question remains: is Moulin’s position in French history warranted? Or was his story hijacked, mythologised and used by General de Gaulle to serve the revival of France, and aid her re-establishment as a world power?

Do you think Jean Moulin was used as propaganda? Does it matter if politicians reconstruct history? Discuss it with us in the comments below.

Image Credits:

1. ‘Proposition de logo de la Résistance française (Jean Moulin et Croix de Lorraine)’ by Gmandicourt, via Wikimedia Commons

2. ‘Plaque rue Jean Moulin, Caluire et Cuire’ by Alexmar983, via Wikimedia Commons

3. ‘Members of the Maquis in La Tresorerie’, via Wikimedia Commons

4. ‘Charles de Gaulle’, via Wikimedia Commons

I live in the town where Jean Moulin’s betrayer came from. I’ve never dared blog about it. I’ve been to the museum above Montparnasse station, which is very interesting, but sticks to the official line about him. I didn’t realise there were rumours he was a Soviet agent.

Thank you for reading my article and for your comments.

As you imply, trying to work out where the truth lies in Moulin’s story is a political minefield—as is so much to do with WWII in France (and in most other countries, by the way).

All I wanted to do was to point out that there are alternative (and conflicting) threads in the popular narrative—especially relating to what Moulin’s motives might have been.

Historian Robert Gildea has suggested that it would be more accurate “to talk less about French Resistance than about resistance in France”. His intention here is to highlight the multifacited nature of the subject, and the wide range of political ideologies and objectives of those who fought against the Nazis.

So, although there is no doubt that Moulin was fighting to rid France of the occupiers, the question of motive or ideology has been raised—not by me, but by many, and more authoritative writers, journalists, historians, etc. (I’ve simply drawn attention to the debate.)

So the question remains: was Moulin’s objective to rid France of the Nazis a bold and courageous end in itself—or did he (like Philby perhaps) have a more utopian world order in mind?

Sadly, it seems that the archives are protected for many, many years—I’ve even read 90. So we’ve all got a long wait for a definitive answer to the question.