N’oublions Jamais…

This time last year, my friend Yvonne Kane was on an Anzac Day pilgrimage to the town of Villers-Bretonneux which has a very special place for Australia in the hearts of its people. [1]

This is an interview about her experiences…

.

Yvie, what was the motivation for your trip?

To meet the staff and students of Jacques Brel College, which has a link with students studying French at Warrnambool College, where my niece Claire attends. I had also been working with the teachers from Warrnambool College in their efforts to get local Aboriginal History taught to Year 9 students.

As students from Warrnambool College are visiting the Jacques Brel school in April 2011 it was also a good opportunity to make connection with the teachers and especially to acknowledge the Aboriginal contribution to the Australian armed forces and the liberation of Villers- Bretonneux.

We had the honour of laying flowers on the grave of Reginald Rawlings, on behalf of his family and the Kirrae Whurrong people of the Gunditjmara Nation of Western Victoria.

Who was Reginald Rawlings?

He was the first Aboriginal soldier to give his life in the battle to free Villers- Bretonneux from the German forces. On the night of 28th July 1918 Rawlings’ Battalion, the 29th AIF with the 32nd Battalion successfully broke through the German lines along Morlancourt Ridge. Reginald Rawlings was awarded a Miltary Medal for his bravery in leading his team down into a German communication trench system. He was killed in action a few days later and buried in the Heath Cemetery Harbonnnières just a few kilometers from Villers-Bretonneux.

What was it like to be an Aboriginal soldier in the Australian armed forces at that time?

There was no equality. Aborigines did not have the same rights as the white soldiers. In fact they weren’t even counted in the Australian census until the 1967 referendum which finally gave them the right to vote. Aborigines were never recognized as being part of the ‘digger’ legend and yet there were at least 300 fighting in WW1. You need to remember too that Australia’s history is built around a white Australia policy where Australia was viewed as being ‘white’. Derogatory terms such as half-caste and quarter caste were used in referring to Aboriginal people; there are countless stories of Aboriginal people being excluded from white society.

How were they treated differently?

Well, there’s certainly little history of it in school textbooks, that’s what’s missing! We simply weren’t told about our local Aboriginal history in schools; even today the full story is not told to students. It is interesting to note that for Aboriginal soldiers there was no return compensation, no granting of land, as was the case with their white counterparts, no war pension – they did not even have the vote.

The public image of the Aboriginal soldier was reprehensible. I’m referring to a well known photo where an Aboriginal Soldier stands out in front of the soldiers with a tethered kangaroo. The notion of the noble savage was shamelessly promoted.

Did the French embrace this concept of Aboriginal soldiers?

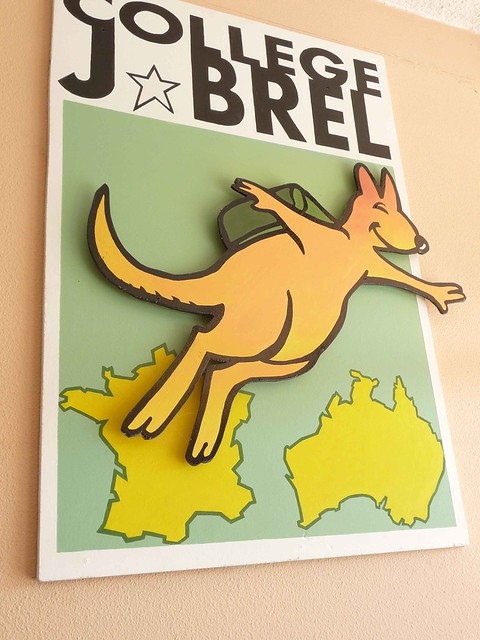

No, not at all. Not only are Australians valued, but the Aboriginal heritage is valued and treated with sensitivity and receptiveness. Walking into the entrance at Jacques Brel School I was surrounded by works of art depicting Australian Aboriginal culture and heritage. There was far more of a connection with Australian Aborigines in this school than I have experienced in schools in the Western District of Victoria.

What was the French perception of Australian Soldiers and Australians in Villers-Bretonneux?

Our arrival at the school in Villers Bretonneux was truly soul-stirring. My heart opened and tears came to my eyes. It was, in fact, more Australian than any school I’ve seen anywhere in Australia. It was covered with Australian memorabilia: flags, photos, posters, banners, displays and wonderful art work completed by the students.

Around the Town Hall were miniature statues of kangaroos and koalas with garlands of flowers. Flags were flying and always the welcoming sign —

It wasn’t just an outward show. These people have a real passion for Australia and Australians, borne of an everlasting gratitude for their freedom and the sacrifice by which it was attained.

You could tell that this wasn’t merely an annual remembrance for Anzac Day; it was there all the year round. The place has such an Aussie flavour; it’s even been nick-named V-B.

What was the experience like for you on a personal level?

It was an Odyssey.

More especially since we had to escape Ireland due to the havoc caused by the Icelandic volcanic ash. Claire and I were committed to visiting the school to meet students, so we re-scheduled. We were determined to get to Jacques Brel school so caught a ferry to Wales, trains, o/n in London …

Claire, by the way, was a tremendous hit with the V-B boys. One young man, with whom she played street hockey wrote later to declare his love “I give you my heart.”

And I wasn’t forgotten either, when he said jokingly!!!

“Yvie, I love you. Will you marry me?”

Therein lies the cultural difference, I can hardly see young Australian males being so effusive in expressing their feelings.

So what happened on Anzac Day?

Claire and I attended the Dawn Service in the chill morning air at the very imposing Australian National Memorial at Villers- Bretonneux. The time and place were truly evocative. This, combined with the solemnity and reverence of the occasion, was deeply moving. No less uplifting and memorable was the ceremony which followed at the French War Monument in the Town Square.

What do you envisage for future links between Warrnambool community, the College, the Aboriginal people and you, personally Yvie?

Whatever the future holds, those ties are there to stay. Claire and I would love to return one day. Students from Warrnambool College are currently in Villers-Bretonneux and will be attending the Anzac Day Dawn Service in 2011. It would be wonderful for members of Reginald Rawlings family to visit one day and feel the welcome of the French.

As the welcoming sign says “N’Oublie Jamais l’Australie” and we will not forget them, but neither should we forget all Australians who gave so much in the name of liberty and I hope this initial visit is a catalyst to establishing that acknowledgement back home.

[1] http://www.anzacday.org.au/history/ww1/overview/west.html.

Context:

Copyright: ANZAC Day Commemoration Committee (Qld) Incorporated

In 1918, the Germans planned one final great offensive in an effort to win the war. At first the Allies were taken by surprise, and the Germans captured many towns and soon were within sight of the town of Amiens. The British High Command feared that if Amiens were captured, the war may be lost. The ANZACs were raced back from Belgium as ‘storm troops’, special fighting soldiers who would be put into battle where they were needed most. At first, the ANZACs fought at Dernancourt (Dern-an-cor) , a town on the road to Amiens, where 4,000 Australians beat off an attack by 25,000 Germans.

Next the Germans attacked the French village of Villers-Bretonneux (Bret-on-er) , after first using poisonous gas and artillery. When night fell, the ANZACs stormed from their trenches and counter-attacked. A British General, who himself had won a Victoria Cross for bravery, called the ANZACs ‘attack’ “perhaps the greatest individual feat of the war”.

The ANZACs then had to enter the village and fight from house to house. Finally, Australian and French flags were raised over Villers-Bretonneux. The ANZACs stopped to bury their dead, 1200 Australians had been killed saving the village. It was not until they were putting the date on some makeshift crosses that they realised the date it was ANZAC Day 1918, three years to the day since they had stormed ashore at Gallipoli.

The Australian flag is still flown at Villers-Bretonneux. It flies atop the Australian National Memorial, on which is listed the names of the 10,982 Australians killed in France who have no known graves. The French have called the main road through Villers-Bretonneux, Rue de Melbourne. The town has a restaurant called Restaurant le Kangarou, and the school, called Victoria College, was built from the donations of Victorian school children in the 1920s.

Above every blackboard are the words “N’oublions jamais l’Australie” ! – Never forget Australia.

What a great article about ANZAC day Christine. I really enjoyed hearing Yvonne’s perspective and I had absolutely no idea that Villers- Bretonneux existed. je te remercie!! Judy

Thanks for this fascinating article Christine. It’s a real eye-opener to hear about Aboriginal soldiers and the terrible way they were treated. I hope your article goes some way towards raising wider awareness of the Aboriginal contribution in World War 2.