What Paris could have been…

id you know that on average, for every ten buildings designed, only one is built?

History is written by the victors – we never hear the stories of those who lost. Architectural history is no different: not only are vast swathes of the built world forgotten, but great masterpieces of the unbuilt world are forgotten too.

This opens up a treasure trove of architectural gems, which although never built, have often had a lasting effect on architecture. Like their built counterparts, I believe these too should be celebrated as part of architectural history.

One of France’s greatest architects epitomises this vision.

Meet French visionary Étienne-Louis Boullée

Étienne-Louis Boullée was a French Neo-Classical architect working in the latter half of the 18th century. At the time he was considered one of the leading Neo-Classical architects, producing several Hôtels in Paris in the Beaux Arts fashion.

Although considered a great architect for his built work, it was his unbuilt work that defined him as a true visionary master. In his latter years, whilst teaching at the École Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées, Boullée developed his idiosyncratic style: a magnificent, oversized and stripped Classicism.

His classical education was combined with a desire to remove the ornamentation associated with French neo-classicism, “stripped of every ornament … light-absorbing material should create a dark architecture of shadows, outlined by even darker shadows.”¹

Boullée had taken the ancient grandeur of geometry and symmetry and re-imagined it for his own time.

Boullée’s ‘Cénotaphe à Newton‘

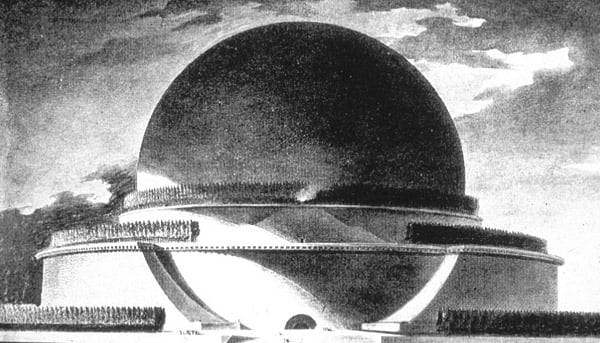

Boullée’s most notable unbuilt work is the ‘Cénotaphe à Newton’, designed in 1784. This was a funerary monument to the English scientist, Sir Isaac Newton, containing a sarcophagus placed at the bottom of a 150-metre-high sphere.

As Boullée was a pioneer of architecture parlante, or architecture that speaks for itself, the monument embodied a very literal expression of science.

In the daytime, the monument recreated the night sky: small beads of light penetrated through the shell to create an all-encompassing star-studded sphere. During the night, an armillary sphere would hang in the centre, emitting a subtle glow; the sun at the centre of the universe.

This remarkable creation embodied Boullée’s belief that “the architect should aim at the sublime.”² Although the structure was never built, it remains Boullée’s greatest legacy.

The legacy of the unbuilt

Boullée’s unbuilt masterpieces were largely overlooked until the mid 20th century when his book ‘Architecture, essai sur l’art’ was published in 1953.

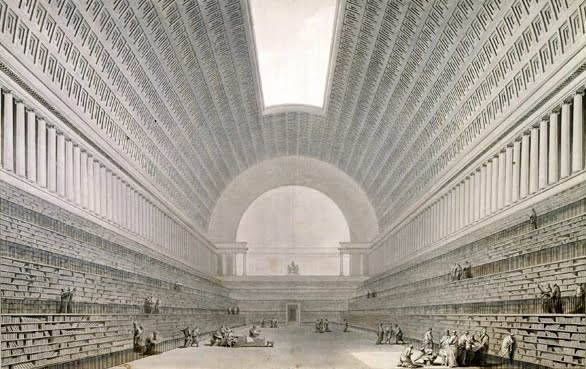

‘Architecture’ largely consists of Boullée’s work between 1778-88. This was the period in which he developed his grandiose, geometric conceptions for public buildings in France, such as the Bibliothèque du Roi (below).

It is these astounding, visionary creations, rather than his built work, which have continued to influence 20th century architects, most notably the Italian architect Aldo Rossi.

How would France look if the unbuilt were built?

Given the precipitous line on which decisions are made, the fabric of the French architectural tapestry could have quite easily taken a different thread.

How might France have looked if the unbuilt were built? Imagine a Paris that hadn’t been re-planned by Baron Haussmann. Or if Le Corbusier’s Unité d’habitation in Marseilles had never been built, would we ever have seen the spread of high-rise housing blocks across Europe?

This is all hypothetical of course, but it begs the question as to how different the path of history may have been.

Then again, perhaps it is desirable that not all of the unbuilt is remembered: the Eiffel Tower’s rival competition entries for the 1889 Universal Exhibition consisted of a granite lighthouse, a giant guillotine and a monumental water shooter.

In some cases, the unbuilt is better off that way.

What fascinates you about France’s architectural history? Join the conversation in the comments box below.

References:1. Étienne-Louis Boullée. Cénotaphe à Isaac Newton (Cenotaph for Isaac Newton) 1784, on ARSCentre.

2. ÉTIENNE-LOUIS BOULLÉ, Newton’s Cenotaph, 1780-93, on Arquitectura en Dibuixos Exemplars. Image credits:

1 & 4. © Hannah Duke

2. Cénotaphe à Newton, 1784, Etienne-Louis Boullée via Wikipedia.

3. Bibliotheque Nationale (unbuilt 1785), Etienne-Louis Boullée via Wikipedia.

That was a very interesting read thank you James. All I know about architecture is what pleases my eyes and what doesn’t. I love intricate, detailed architecture with creatures, other features and tiny attics seemingly put there for the architect’s delight for us to find if we look up. That’s one reason why I love Paris. Each time I’m there I do get a bit choked up when I enter the city for the first time. Melbourne still has a few gorgeous buildings remaining and I’m lucky enough to gaze at one as I write this. Next year I’ll be looking at Paris buildings as I write. Thanks again.