How to read French gothic cathedrals: secrets set in stone

In the first article of the series, we explored the rise (literally!) of French gothic cathedrals.

The night illuminations of Amiens Cathedral are a magnificent sight to see. But how many of us, when we visit a gothic cathedral during the daytime, take a few moments to stand back and look at the front façade?

It’s well worth it. Here’s why.

First impressions tell more than you think

Cathedrals give away many secrets before you ever step inside. The typical French Gothic cathedral has a ‘front’ façade with two towers on the western side. Reims is a good example, noted for its beauty and unity. This is because it was built in a single phase of construction.

By contrast, what does the uneven western façade of Chartres cathedral tell us? It emerges from an earlier Romanesque building that was partially destroyed in fire, then rebuilt in the new Gothic style.

Amiens’ towers were built fifty years apart, in quite different styles, and a long time after the rest of the cathedral.

The façade of Rouen’s cathedral indicates not only its slow construction of the building but some of the fights along the way! Its famous Tour de Beurre was constructed well past the gothic age, in the early sixteenth century.

It was popularly believed that the tower’s construction had been funded on the back on the Church’s dietary restrictions during Lent. At that time, Christians were not to indulge in rich foods like butter, and those who did were required to pay a fine of six deniers tournois.

Looking at the height of the tower, good French butter was evidently as popular then as it is now!

Behind French façades

French Gothic cathedrals had more than one façade and entrance. Each façade was used for a different purpose and so communicated different messages. These were part of a carefully planned Christian framework.

French Gothic cathedrals had more than one façade and entrance. Each façade was used for a different purpose and so communicated different messages. These were part of a carefully planned Christian framework.

At Notre-Dame de Paris for example, the north façade faces the cold, and depicts figures from the Old Testament. However, the south portal, which gets more sunlight, celebrates the coming of the Messiah and stories from the New Testament.

The western façade is often the most impressive. This is also the case in Paris, where a long row of 28 kings of Judea look over the congregation entering below.

During the French Revolution, people desecrated these statues thinking they were sculptures of the French kings.

The heads you now see are mostly now replacements but some of the originals that were discovered in later excavations are on display in curiously disembodied form in the wonderful Musée de Cluny.

Gothic cathedrals – portals to another world

In times when most people couldn’t read, the messages of the Church and the Bible had to be told in pictures. And as the illuminations at Amiens show, they could be colourful too!

In some places – Amiens is one – traces of the original colours can still be seen on the sculpted figures surrounding the doorways (see the image below).

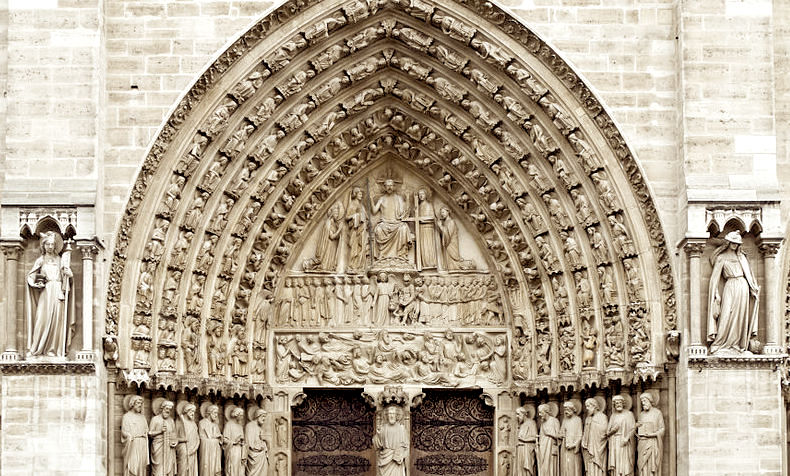

Above the entrance doors, in the arches or tympanum, many French Gothic cathedrals have a key story about the Virgin Mary, Christ in Majesty or the Last Judgement.

At Nôtre-Dame de Paris, the central entrance door has a sculpted figure of Christ as a central jamb figure, or trumeau, welcoming in parishioners. If they looked up as they walked in, they would have been reminded of the fate of all Christians: to have their souls weighed in the Last Judgement.

In the lowest level of the scene, the dead are rising out of their coffins, woken by angels.

In the middle level, they’ve been sorted into two groups – on the left hand side as we look at the image are the good, nicely lined up. But on the right-hand side are those enchained and on their way to hell, dragged by demons.

Finally, at the top of the scene, and sitting in judgement, is Christ himself. Around him are Mary, John, and a multitude of angels, who are interceding on behalf of particular souls.

These were messages that everyone could read and understand, and they were repeated at most cathedrals and in many other places, such as the medieval hospital at Beaune.

More to French façade sculpture

But façade sculpture was not all doom and gloom. It told stories of hope, miracles, martyrs and the everyday world of the Middle Ages that would be familiar to the congregation.

Noted for their serenity and stylised drapery, the jamb statues at Chartres cathedral, which include biblical figures, saints and martyrs, welcomed visitors through the doorways. They are about 50% larger than human size, so they sent a message that they were once like us and yet, as befitting their spiritual status, represented something greater than humanity.

The left bay of the North transept façade at Chartres shows the Ascension of Christ into heaven occurring above the everyday rhythms of earthly life, seen in the zodiac signs and labouring activities of each month.

So next time you are visiting a Gothic cathedral, don’t be in a rush to go straight in. Looking at its façade can reveal many secrets to its history, if you know how to read it!

In the next in this series, we’ll open up the cathedral doors and discover what is to be found inside.

Why do you like (or dislike!) visiting Cathedrals in France? What are your favourite aspects of the architecture and experience? Share with us in the comments box below!

Read more on gothic cathedrals…

Part one: discovering secrets

Image credits:

1. Amiens Cathedral, © Raimond Spekking / CC BY-SA-4.0, via Wikipedia Commons.

2. Nôtre-Dame de Paris by Andwhatsnext via wikipedia.

3. Slight colouration on the central tympanum, Amiens Cathedral © Guillaume Piolle via Wikipedia.

4. Central tympanum, Nôtre-Dame de Paris, Carlos Delgado via Wikipedia.

5. Central tympanum, ? Nôtre-Dame de Paris, Urban via Wikipedia.

6. Jamb statues, Chartres Cathedral, Mattana via Wikipedia.

7. Aries, Taurus and Gemini and agricultural labour, Amiens cathedral, HaguardDuNord via Wikipedia.

Just a little correction. It is anunfortunate misconception that most people couldn’t read back then. Since the days of Charlemagne most people were thought to read. The thing is, younwere only considered literate if you knew Latin. That’s why we think people were a bunch of illiterate. Well, most of them were for their standards. But for ours, not really. They still couldn’t read the Bible (yet) because it was in Latin. And of course there was more people that couldn’t read than today (almost no-one is illiterate in France today), but by no means they were as mostly illiterate (for our standards, anyway).