Discovering secrets of the French gothic cathedral

Gothic cathedrals are beautiful monuments of a past age that litter the landscape of France. An Tampere shared her four most beautiful cathedrals for MyFrenchLife™ and included Paris, Amiens and Chartres among them. But why are they there and how can we read them?

Gothic cathedrals are beautiful monuments of a past age that litter the landscape of France. An Tampere shared her four most beautiful cathedrals for MyFrenchLife™ and included Paris, Amiens and Chartres among them. But why are they there and how can we read them?

Come on a journey that explores how we can appreciate the French gothic cathedral. In this series, we discover how these stunning testaments to faith changed the face of France.

Where are the best gothic cathedrals in France?

One thing you might notice straight away is that many French gothic cathedrals are in northern France – Sens, Laon, Soissons, Chartres, Amiens, Beauvais, Reims, Saint-Denis and of course, Paris. But why is that?

Gothic cathedrals were not the first spiritual buildings to rise in medieval France – magnificent Romanesque cathedrals preceded them – but something special was going on in France at these particular sites. They arose as a response to two movements: one being an increase in urbanisation and the other a change in spiritual practices.

Spiritual fervour in medieval French towns

For a long time, those who wanted to live a spiritual life had been encouraged to join a monastery. This led to a series of remarkable monastic sites, such as Abbaye de Fontevraud, where it was women who were in charge of both monks and nuns. As was the case at Fontevraud, these institutions grew and grew, outliving their avowed attempt to isolate people from their worldly surrounds – too much of the world had entered the cloister!

Although monastic life remained popular, by the 12th century, people sought out new ways to express their faith. The north of France became distinctly urbanised as people flocked from the countryside to the towns where they could work in organised guilds and trade their goods in regulated ways. Although these people didn’t want to join a monastery, they still wanted to show themselves to be good Christians.

As a result, they began to use church buildings as a place to display their fervour. This happened in a number of ways. Some individuals, especially kings and queens, paid for entire building projects.

Notre-Dame d’Amiens, for example, was built from the profits of the cultivation of woad, a plant from which a blue dye could be made. Such art projects served as a visible expression of their strong religious feelings.

Practically speaking, cathedrals took a long time to build, often more than the lifetime of a single individual.

Their progress needed a level of organisation and focus that was easier to sustain within an urban community.

French gothic cathedrals as glorified reliquaries

Soon, these urban building projects became quite competitive. Civic pride made townspeople keen to make sure that their cathedral had the tallest towers, the large nave or the most startling relics.

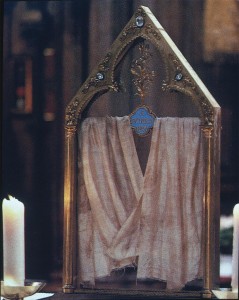

Relics were artefacts that were believed to be part of the body, or a possession of a saint. They were seen to hold extraordinary powers and provided a palpable link to the spirit world and intercession of the saints. These objects were housed in precious reliquaries within the great churches.

Many of the gothic cathedrals of France were essentially glorified reliquaries for the community’s most prized possessions and were worth far less in spiritual terms than the objects they housed.

For example, Amiens cathedral was famed for holding the supposed head of John the Baptist, brought back from the Crusades in 1206. You can see a replica of this now lost artefact in the north aisle.

At Notre-Dame in Chartres, it was the silk tunic of Mary, mother of Jesus. This precious cloth (pictured above below), given to the cathedral by Charles the Bald in 876, somehow survived major fires that burned down earlier constructions on the site – only increasing the miraculous powers that were attributed to it.

He had purchased many of these from the Emperor of Constantinople for a price that was more than four times the cost of the entire construction of the chapel. When the treasured objects arrived in Paris in 1239, he walked barefoot, as a sign of his humility, through the streets of the city to greet them.

French gothic cathedrals as waypoints for pilgrims

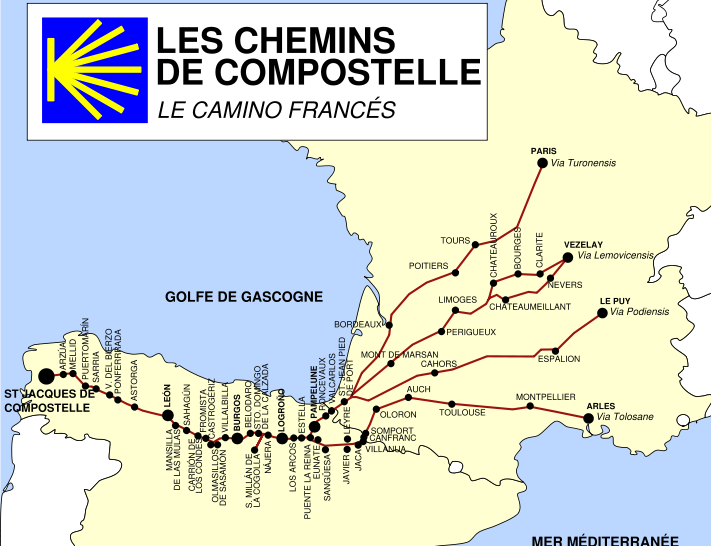

Gothic cathedrals also often marked gathering or waypoints along known pilgrimage routes. The route became extremely popular when in 1140, a French monk named Aymeric Picaud composed an account about travelling to the shrine of Saint James at Santiago de Compostela in north-western Spain.

There were a number of known pathways across France and several official starting points, including Paris, Vézelay and Le Puy. Cathedrals offered spiritual visiting points and sold souvenirs of their famed relics to pilgrims who often collected mementos of their journey.

People still walk these pathways today, taking a meandering, reflective pace through the French countryside.

In the next article of the series, we’ll start to read the stories told by cathedrals through their art and architecture.

Which are your favourite gothic cathedrals in France? Let us know by leaving a comment in the box below!

Read more on gothic cathedrals…

Part two: secrets set in stone

Image credits:

1. Cathédrale Saint-Étienne de Bourges, by Renaud Mavré, via Wikipedia.

2. Cathédrale de Chartres, by Ireneed, via Wikipedia.

3. The Cathedral of Our Lady of Amiens, by Jean-Pol Grandmont, via Wikipedia.

4. Châsse Saint Taurin, by Theoliane, via Wikipedia.

5. Sainte Chapelle – Upper Chapel, by Didier B, via Wikipedia.

6. The Veil of the Virgin in its Reliquary, via Textile Relics.

7. Camino de Santiago, by Daniel Hieber, via Wikipedia.