King Kong Théorie, Virginie Despentes – in theatre: unsettling, raw, fantastic

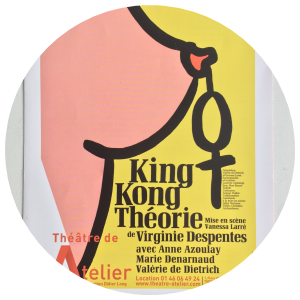

From the 4th October 2018, a theatre adaptation of Virginie Despentes’ 2006 book King Kong Théorie is showing at Théâtre de l’Atelier in Paris. A charged, honest and often humorous text, the book is a part-autobiography, part-manifesto which centres on women’s experience, sexuality, gender and the often-violent relationship between masculinity and femininity.

From the 4th October 2018, a theatre adaptation of Virginie Despentes’ 2006 book King Kong Théorie is showing at Théâtre de l’Atelier in Paris. A charged, honest and often humorous text, the book is a part-autobiography, part-manifesto which centres on women’s experience, sexuality, gender and the often-violent relationship between masculinity and femininity.

King Kong Théorie : militant feminism mise en scene

The play is often unsettling, brutal and raw. Nonetheless, it remains exciting and enjoyable to watch. Much like the book, some moments are even humorous – whether that be nervous or genuine laughter – often about the cynic outlook of society and women’s place within it.

The play covers rape, prostitution, pornography. Fundamentally, it asks: ‘what is femininity’ and puts into question what type of society we want for tomorrow.

Bad Lieutenantes: opening King Kong Théorie

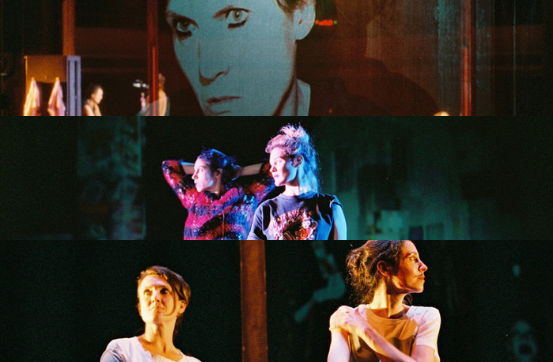

The play centres around the confessional monologues and interactions of the three actresses on stage, each a manifestation of Virginie Despentes’ voice and experience. These actresses – Anne Azoulay, Marie Denardaud and Valerie de Dietrich – appeared first on stage in punk-style attire, much like Despentes herself. Opening the show, they each in turn spoke the words from the opening pages of King Kong Théorie:

« Parce que l’idéal de la femme blanche, séduisante mais pas pute, bien mariée mais pas effacée, travaillant mais sans trop réussir, pour ne pas écraser son homme, mince mais pas névrosée par la nourriture […] de toutes façons je ne l’ai jamais croisée, nulle part. Je crois bien qu’elle n’existe pas. »

From the start, the audience is forced to reflect on the idea of gender and femininity. And this was just the beginning.

The mise en scene is simple. A stage lit dimly with an overhanging red light, a few chairs, two lockers, a guitar. The simplicity of the set up allowed the focus to be on the women, and importantly, their words.

Chapter 3 : Impossible de violer cette femme pleine de vices

Perhaps the most unsettling moment in the book is translated beautifully, for lack of a better word, for the stage. Announced as an event from “Juillet 1986” when Despentes was just seventeen years old, each of the actresses launch into a monologue recounting the story.

Unsettling background music and a screen projection of a parking lot set the atmosphere: disturbing. This scene is an autobiographical account of Despentes and a friend being raped one night when they were hitchhiking.

Azoulay and Denardaud come close, hold hands, then gradually separate as the story unfolds. De Dietrich sits in the background, staring into space, as if this part of Despentes’ struggles to vocalise or engage with the memory. The women smear blood on one another. These stains will remain on the women throughout the play. For me, this is a gesture which symbolises the effect such an event has on a woman for her whole life. Simultaneously, it represents the unity of these women who, as the play states, are ‘victimes ordinaires.’

Chapter 4: Coucher avec l’ennemi, part 1 – prostitution

At this point, the play deals with prostitution and porn. I found one of the most effective techniques in the play to be the use of a camera – directly projected onto the screen – that the women used to film themselves.

De Dietrich changes from a masculine attire to a red mini skirt and heels. The women produce monologues of the experience of working as a prostitute. They recall Despentes’ words:

‘La prostitution a été une étape cruciale, dans mon cas, de reconstruction après le viol.’

Denardaud removes her shirt. The dialogue centres around the overwhelming sense a woman has of being present and of her body being watched. Her sexuality being the centre of attention. The camera films the audience; we also feel the sense of being entirely present as we watch ourselves being watched.

Part 2 – pornography

The scene about pornography was as humorous as it was hard-hitting. A man next to me laughed nervously and repeated ‘c’est pas possible’ as Azoulay mimicked a blowjob using her thumb, then as the three women recreated sex positions and shot ping-pong balls out their mouths into the crowd.

For me, this was the point. The aim: to demonstrate how pornography is the realisation of masculine fantasy. To show that porn is a male prerogative, that female sexuality often does not get a word in edge-ways. Pornography is simultaneously over-censored and yet we all secretly watch it. It’s uncomfortable, and it’s real, so we laugh. And women ought not be ashamed of their sexuality.

The play momentarily becomes ‘interactive’ as the actresses point the camera on us once again and ask the audience to say something about female masturbation. No one spoke. Perhaps, again, this was the point. I felt the unsettling atmosphere as no woman was prepared to stand up and give details about her masturbation… I’m tempted to go another night and see if the reaction changes.

Chapter 5: King Kong Théorie – the manifesto

Moving on, the scene that correlates to the chapter ‘King Kong girl’ becomes less personal and more philosophical. An image of Skull Island – that from the 2005 film – is projected at the back of the stage. Azoulay, in a blonde wig and pink dress, represents ‘la belle’ next to the bête, King Kong. I remember how the words at this point resonated with me as the intellectual core of Despentes’ text was read aloud:

‘King King, ici, fonctionne comme la metaphore d’une sexualite d’avant la distinction des genres […] King Kong est au-dela de la femelle et au-dela du male. Hybride, avant l’obligation du binaire. L’ile de ce film est la possibilite d’une forme de sexualite polymorphe et hyperpuissante.’

‘La belle’ is dressed in a pretty pink dress while sporting a drawn-on moustache. This gets quite a few laughs. The other two actresses change back into more androgynous attire: jeans and t-shirts. A man’s blazer. It is at this point in the production that the optimism, or at least hope, for tomorrow’s society comes to an apogee. The idea of binary oppositions in gender are deconstructed both through the dialogue and the visuals.

Salut les filles: an attempt to summarise

I can confidently say I was never bored watching this production. In fact, I was completely engaged. The choice to have three actresses portraying Despentes’, her voice and her outlook, was outstanding. Their interaction with one another on stage – sometimes entirely cohesive, sometimes questioning one another – expressed the internal dialogue of a woman coming to terms with her personal life and past, as well as her relation to the society in which she lives. What’s more, each one of their performances was absolutely faultless.

If they talk about putes (whores) and bites (dicks) a lot, it’s because this is the language we use when discussing sex and sexuality. It’s honest – a militant text that uses ‘real talk’ to present problems and hypocrisy in society today. It’s the reality of not just Despentes’ life, but a wider relation between men and woman and their relationship to sex, sexual identity or representations of masculinity and femininity. The play was raw, it was simple. It was to the point. Sometimes shocking. Sometimes uncomfortable. And yet, there are sparks of humour amongst intense monologues.

Finally, Bravo to Vanessa Larre for putting together the theatre production of this book. It guides your emotions to naturally react to and reflect upon what is in front of you – making you feel a certain way before you even realise it yourself.

Have you read or seen Despentes’ King Kong Théorie? Or perhaps some of her other work? We’d love to hear your thoughts and reflections in the comment section below.

Image credits

- 1, 2, 4 & 5. © Lauren Smith

- 3. photos via Théâtre d’Atelier website, edit is the author’s own