French Philosophy Gems for Mental Health: Existentialism

Ideally, philosophy articulates readily into conversations to help us with our sense of meaning and purpose in life and offers lenses through which we can better understand and cope with challenges. Better still, it may offer comfort through wisdom, hope, and insights.

Existentialism is not a warm or fuzzy philosophical frame. Yet for me, it’s rich in wisdom and a ‘street-wise’ brand of comfort. It focuses on the questions of human existence itself, and the human condition of feeling, or perhaps ‘fearing’, that there is no purpose or explanation at the core of existence. Essentially, existentialism gives us permission to acknowledge vast themes like emptiness, uncertainty, fear, and the mystery of life and still create empowered lives.

Modern existentialist thinking is generally seen as coming of age in mid-20th century France, although writings on existential themes stretch back into antiquity, particularly in some early Buddhist and Christian works.

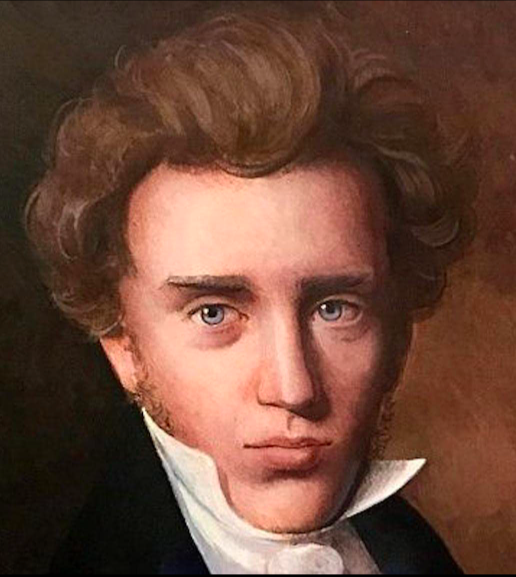

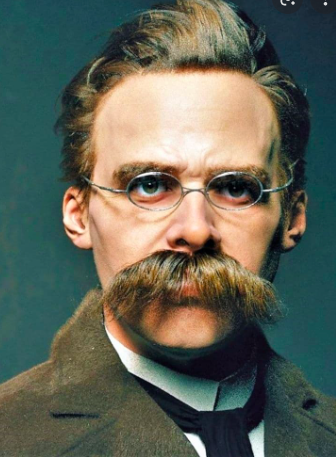

Early modern existentialists include the Danish Søren Kierkegaard, German philosophers Friedrich Nietzsche and Martin Heidegger, and in France, Blaise Pascal.

Later came the work of the modernists of the movement for whom the term ‘existentialist’ was coined: Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and novelist Albert Camus.

Chances are, if you’ve ever experienced any counselling or psychological therapy, or even read a self-help book, you’ve been exposed to some level of existential thinking. Let’s draw out some of its key concepts to appreciate their importance in supporting mental health.

Valuing individual experience

Existentialism offers the perspective that individuals create their own meaning in life. It acknowledges that humans attempt to function rationally, despite existing within a mysterious, often irrational world.

Existentialists purport that understanding life through lived experience is better than taking on belief systems unquestioningly. It values our power to shape ourselves and our lives while acknowledging that there are some inescapably disempowering aspects to life.

A realistic perspective on life

Albert Camus’ motto “Live and create in the midst of the desert” is a stoic, real, and inspiring perspective for me, although I understand why some might find it a dark view. It can be reassuring to focus on what we can do as individuals, to create and express ourselves, even when the world feels absurd, or at worst, meaningless or cruel.

Accepting the unknown

It can be therapeutic to accept the absurdity of life as a human and the mystery we live in, without needing to explain it according to any doctrine. To accept things we cannot change, and take ultimate responsibility for those we can, is mightily important for healing, recovery, and living intentionally and authentically.

Freedom of beliefs

While existential thought generally holds that beliefs are entirely individualistic, and tend to be atheistic, there have indeed been religious existentialists such as Blaise Pascal. The liberal nature of existentialism allows for freedom of beliefs.

In many countries, increasing numbers of people do not have a religious faith and cannot authentically turn to religion for comfort in difficult times. Existential therapeutic conversations can offer support, strength, and hope for those who don’t subscribe to an organised religion.

Make your own meanings

In most existentialist thought, meaning is not provided to you by the world, by other people, or by God. Sartre wrote:

At first [Man] is nothing. Only afterward will he be something, and he himself will have made what he will be.

Is that lonely or even terrifying? Potentially, yes. However, beyond the fear, is such a perspective not also potentially freeing and authentic?

In sum, I think such a perspective tends to bolster courage, empowerment, and possibility. Having hope, personal responsibility, and acceptance about what we can and can’t control, are all generally important components for optimal mental health.

To me, existential conversations are so potentially helpful because they aren’t about sugar-coating our circumstances, leaving us feeling as though we’re lying to ourselves that everything’s great when actually isn’t. They don’t run from the mystery and struggles of human existence but confront them head-on, which is precisely what growth and healing typically require.

What are your experiences of existential conversations, in or out of therapy? Do you find existential conversations or reading essentially comforting, or too dark? Let us know in the comments, Debra is very interested to hear your thoughts.

Image credits:

1. Image by Frank McKenna on Unsplash

2. Danish – Søren Kierkegaard

3.- 4. German philosophers – Friedrich Nietzsche and Martin Heidegger

5. French – Blaise Pascal

6. French – Jean Paul Sartre

7. French – Simone de Beauvoir

8. French – Maurice Merleau-Ponty

9. French novelist – Albert Camus