Review: I’m Gone

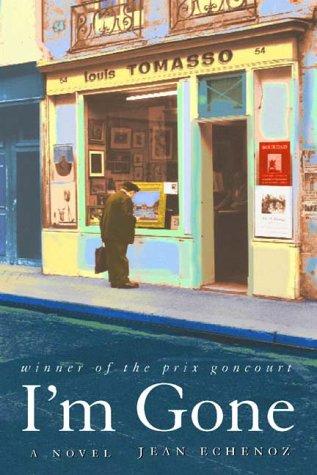

I’m Gone by Jean Echenoz (translated by Mark Polizzotti) won the Prix Goncourt, the prize for ‘the best and most imaginative prose work of the year’ in French literature.

It was an immediate bestseller in France, and since being translated into English, it has made a significant impact on that market too. The New York Times‘ Book Review described it as ‘vivid and entertaining’ and the Washington Post hailed Echenoz as ‘the distinctive voice of his generation’ and ‘the master magician of the contemporary French novel.’ The Library Journal, in my opinion was spot on, by calling it ‘a sly send-up of contemporary art and life’.

I’m Gone opens with Felix Ferrer, a Parisian art dealer, telling his wife he’s leaving her. He drops his keys on the table and walks out. “…I’m gone”, he says. An immediate insight to a detached, middle-aged man, who was once a renowned sculptor.

The second chapter jumps forward six months to see Ferrer at the airport going to the Arctic circle to retrieve rare antiquities from a ship wreck. And so starts the darting between place, time and character, which Jean Echenoz does purposely. Echenoz even changes perspective – from third to second, as the narrator, or reader confidante, pauses from telling the narrative to talk directly to the reader; “Personally, I’ve had it up to here with Baumgartner. His daily life is too boring,” he/she says.

In fact, the narrator often seems pleased with its apt turn of phrase used to transition between chapters and at times can be a bit of a know it all. He/she lets the reader know more about the hapless characters’ present and future then they know, for example the narrator points out instances where characters just miss confrontations and other probable moments of revelation. Through the narrator’s ominsence, Echenoz subverts narrative expectations as only a true master can; ‘But had someone also informed him that, of the three people gathered there that evening, each would disappear… before the end of the month, himself included, he would have been supremely concerned,’ the narrator foretells. Reflecting on the story, there were also hints about the outcome peppered throughout.

The narrator is also opinionated; when describing the Arctic, he/she says ‘These are territories where no one ever goes, even though a fair number of countries have more or less claim to them…[including pretty reasonable historic and geographic reasons]…and the United States, because it’s the United States.’

Echenoz’s descriptions are precise and original. Arctic icebergs, he writes ‘…seemed more discreet, more worn-out than their Antarctic counterparts… They were also more angular, asymmetrical, and ornate, as if they had twisted and turned several times in troubled sleep.’ The ship was ‘…dusted with frost and looking brittle as dead wood’.

The way Ferrer describes and thinks about people provides great insights into his character and demonstrates Echenoz’s literary skill (and possibly his own opinion of people, as all the characters are emotionally and morally void):

‘Delahaye was a man made entirely of curves. Hunched spine, gutless face, and an asymmetrical, uncultivated mustache that spottily mashed his entire upper lip and curled into his nostrils.”

‘Delahaye’s gestures were undulating, rounded; his thinking was as sinuous as his gait…’

Ferrer is superficial, arrogant, bitter and manipulative; he says to Delahaye about the art gallery’s customers, “You have to argue with them sometimes, give them the impression they’re thinking for themselves.”

He is equally detached about his relationships. He sleeps with no less than eight women through the book, from his neighbour, to the art appraiser’s assistant and to the daughter of a family who houses him in isolated Arctic village. The narrator shares the audience exasperation over his womanizing, asking, ‘Isn’t it about time Ferrer settled down?’ On the next page, his cardiologist says, “…[Y]ou’re going to have to stop fucking around so much for awhile.”

His quest for the antiquities provides rare moments of engagement. It also signifies the extent to which his life has quickly changed. Before leaving his wife, his life was staid:

‘He always washed in the same order… He always shaved in the same order… And since Ferrer, subject to these immutable orders, asked himself every morning how to break out of this ritual, the question itself became incorporated into the ritual.’

There are some other funny moments in I’m Gone, the ones that made me laugh most involved a funeral ritual and baby monitor.

Echenoz also points out the absurdity of modern life; a policemen’s monologue about the emptiness of his life goes on for a page and the narrator sniggers at the suggestion that you could feel sorry for the rich Parisians whose homes are so big, they are empty and cold. Paparazzi hide out in bushes, and Ferrer worries about swearing when he bashes a man. The contemporary art scene does not escape Echenoz’s scorn. The meaninglessness of modern life is emphasised by the story literally coming full circle.

Echenoz subverts the narrative conventions and transforms contemporary life into a bizarre, bleak and often funny tale of adventure and mundanity.

Image credits:1. Paperback

2. torre.elena on Flickr