The French education system: where is it going wrong?

Last month, the latest batch of final year secondary schoolers in France took the baccalauréat, the equivalent of the UK’s A-Levels. For many, the exams went well. However, others claimed that certain questions in the 2015 baccalauréat were too hard.

Last month, the latest batch of final year secondary schoolers in France took the baccalauréat, the equivalent of the UK’s A-Levels. For many, the exams went well. However, others claimed that certain questions in the 2015 baccalauréat were too hard.

According to Le Figaro, in 48 hours, 10 000 students signed an online petition against a difficult question in the English language exam this year. This made me wonder: does the French education system expect too much from its students? And what happens to those who get left behind? With only 47% of French students getting through the first year of their degree, where is the French education system going wrong?

After experiencing the French education system for six years, I wanted to give my personal opinion on what I think is happening here.

High expectations from the beginning

Most French parents place huge importance on their children’s grades and behaviour from the earliest stages of their schooling. The typical French school day is long. Starting at approximately 9am and finishing around 4.30pm, this can be tiring, especially for those in rural areas who have to catch the bus at 7am to be at school on time. Summer school will also help get grades up if they are slipping.

On top of that, tests are frequent, with at least a couple of interrogations happening every week. These count towards the children’s final grades at the end of the year: the dreaded moyenne. When I was at school in France, after spending ten hours out of the house (most of those in a classroom) the last thing I wanted to do when I got home was study for the next test.

And then there are the exams, which are gruelling. In French secondary schools, pupils are required to take philosophy classes, and the philosophy baccalauréat exam lasts four hours. This begs the question of how can one can be expected to concentrate for that long and produce good work. And is four hours of philosophy even necessary? But this is what French schools expect from their pupils, and parents usually reinforce these expectations at home.

Forcing square pegs into round holes

The French education system forces square pegs into rounds holes: the square peg being the child, and the round hole their expectations of him or her. The general view is that academia is the only thing a young person should focus on, which seems to be somewhat archaic to me. The more creative subjects are for those who aren’t smart enough to take the scientific ones, and if you struggle to understand something, or you stray from the road to academia, you are looked down upon.

I have countless peers from my education in France who find themselves lost, unable to decide what they want to do with their lives, and unable to support themselves because they have spent their student loans on rent while studying for degrees they ended up hating and abandoning – once, twice or even three times. This, to me, is devastating.

Conservative teaching methods

The focus of French education is on exams results instead of actually learning. Rote learning is the main way French children ‘learn’. Students are used to cramming: my friends would learn five pages of the textbook to be able to recite it on paper the next day, then promptly forget what they had memorised (I personally didn’t have the will power to bother, hence my disastrous moyenne!).

Primary school children memorise poems that they recite in front of the class in preparation for the cramming they will have to do later on in their school life. After la maternelle (ages 2-6), which focusses on drawing, painting and other artistic projects, there is little space for creativity or individuality in the curriculum.

Keeping children back a year if their moyenne is not high enough is also common. Called “redoublage”, this can leave children frustrated and disheartened. When my parents disagreed with my school’s choice to keep me back a year, my mother and I found ourselves in front of a jury of about 15 people who had never met me before.

It is also not uncommon to see the teacher reading out the ranking of children at the end of the year according to their grades, from best student to worst. This is another side effect of placing too much importance on standardised testing and higher education.

Elitism and humiliation

In my experience, teachers in France won’t hesitate to tell a child he is “mal-élevé” (poorly raised). Humiliating children is more widely accepted in France, and the teacher is always right. Only the best students are treated well by teachers – only they will be able to join the elite ranks of the academics in the future.

One time, when I failed to answer a question about English history, the teacher encouraged the class to mock me. Another time, in year 7 maths class, my teacher gave up on me and left me to sit at the back of his class once he had finished mocking my attempts at answering questions.

A need for modernisation?

I am sure that not all experiences of the French education system have been as bad as mine. In fact, mine wasn’t all bad. For my first year of school in France, I had a wonderfully dedicated teacher who considered creativity as important as getting good grades. She would takes us for long walks in the fields above our school and would let us flock to the window with our sketchbooks when a deer walked by. I have a five-year-old sister in education in France, and although it took a lot of tears and persuasion to make her go willingly, she now loves school.

I am sure that not all experiences of the French education system have been as bad as mine. In fact, mine wasn’t all bad. For my first year of school in France, I had a wonderfully dedicated teacher who considered creativity as important as getting good grades. She would takes us for long walks in the fields above our school and would let us flock to the window with our sketchbooks when a deer walked by. I have a five-year-old sister in education in France, and although it took a lot of tears and persuasion to make her go willingly, she now loves school.

Perhaps there are some good aspects to a French education, and these probably differ from school to school. Over the last few years, extra help for special needs children is now offered in some schools, for example, with dyslexia. However for me, the narrow choice of subjects and lack of alternative teaching methods, the overbearing amount of standardised testing, and the lack of guidance and respect for students who do not wish to become doctors or lawyers, suggest that the French education system desperately needs to be modernised.

What do you think? Have you experienced the French education system? Let us know what you think in the comments below!

Image credits:

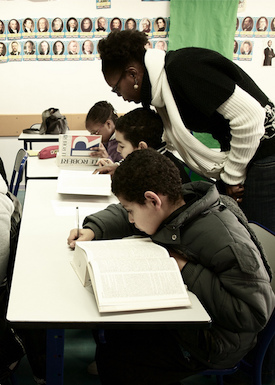

1. The importance of the teacher, by Bob Cotter, via Flickr.

2. ZeLIG Admission exam 2010, by ZeLIG School, via Flickr.

3. Studying, by Steven S., via Flickr.

4. Salle de classe, by Etrusko, via Flickr.

5. Lycée national, Arras, by Shaun Dunphy, via Flickr.

As a French, I admit that it’s how it is. But this post is a bit old and some things changed. For exemples, at the beginning of year 11, u have a lot -to much- possibilities for your studies. School no longer starts at 9am but at 8am and, from year 11, it goes until 6pm.

In overall it is a good post 😀