Who were the French suffragettes?

France was one of the last countries to give women the vote in 1944 and French women have been campaigning tirelessly for their rights since 1789.

From the Women’s Petition addressed to the National Assembly during the French Revolution to the French Union for Women’s Suffrage, the determination of these women showed itself countless times. In honour of these admirable women, we have made a list of some of the most influential French suffragettes.

Olympe de Gouges

Olympe de Gouges, born in 1748, wrote the ‘Déclaration des droits de la femme et de lacitoyenne’ and addressed it to Queen Marie Antoinette. This document introduced the issue of women’s rights directly into the French Revolution.

Around the same time as the March on Versailles, carried out by women rioting against the high price of bread, Etta Palm d’Aelders produced a pamphlet proposing that a group of women’s clubs be organized throughout the country in order to begin a sort of welfare programme to “supervise efficiently the enemies harboured in the midst of the capital” and to support men in the army.

For the first time, female-only political clubs were appearing, slowly widening the political scope of women, and eventually giving birth to issue of female citizenship. Olympe de Gouges, a French writer who had already written a number of pieces against slavery, was alarmed when the French constitution of 1771, which promoted equality, did not even consider women’s suffrage. It spoke of equality between men, but did not address the plight of women.

De Gouges insisted that women must take their freedom instead of waiting to be given it by men, which would contradict entirely the message of the declaration. She summed up her ideas about women’s rights in this simple sentence: “Woman has the right to mount the scaffold; she must equally have the right to mount the rostrum.” If women have the right to be executed, they should have the right to speak.

Olympe de Gouges was executed by guillotine during the Reign of Terror for attacking the regime of the Revolutionary government and for her close relation with the Girondists. She was the earliest French feminist to demand the same rights for women that were given to men.

Pauline Léon & Claire Lacombe

On January 1, 1789, a document titled ‘Petition des femmes du Tiers État au Roi’ was addressed to the King, stating that women wanted equal educational opportunities. Along with the argument for education there was also an argument put forward for equality of sexes. It was the French Revolution, and the climate of change, that created strong feelings in the women of society. In 1793, political chaos reigned. The Jacobins, the leading political force of the era, punished ruthlessly those who disputed their views. Rivalling them were the Girondins. In February 1793, a group of women requested the use of the meeting hall of the Jacobins for a meeting of their own. The Jacobins refused. Some say that they feared a “massive women’s protest”.

The group of women, who now called themselves the Assembly of Republican Women, persisted and received permission from the Fraternal Society of Patriots of Both Sexes to use their meeting hall. The assembly’s main aim was toward economic stability. However, for some this was not enough. They wanted more political activity.

On May 10, 1793, suffragettes Pauline Léon and Claire Lancombe founded the Society of Revolutionary Republican Women, and registered it at the Paris Commune. It was a feminist society, yet saw its role as defending the revolution. However, many women disliked the society for numerous reasons; one being that the society had signed a petition insisting that all women wear the red cockade.

Women became suspicious of each other, until a number of them demanded that the Society of Revolutionary Republican Women be abolished. This action did not only lead to the end of the society, but also all other women’s organisations. Chaumette, the sans-culotte who dissolved the society, jumped at the chance to confine women once more, stating that it was his right to expect his wife to run the home while he attended political meetings – this was as far as her civic duties should go.

Despite this, the Revolutionary Republican Women gave women a political role, encouraging them to make their voices heard.

Nathalie Lemel and Élisabeth Dmitrieff

Nathalie Lemel and Élisabeth Dmitrieff founded the Women’s Union in 1871. Lemel was a bookbinder born in 1827. She left her husband and travelled to Paris with her three children. She began her career as an activist in 1864, when bookbinders went on strike.

In 1865, Lemel joined the International Worker’s association, and when a new strike was called, she was a member of the strike committee and elected union delegate – a rare position for a woman to hold in those days. She fought for equal pay between men and women and began to make speeches in women’s clubs.

Dmitrieff, born in 1850, was the daughter of Tsarist official, a relation of Karl Marx and co-founder of the Russian section of the International Worker’s association. After studying the London worker’s movement, she was sent to cover the events of the Commune in Paris. She set up the Women’s Union as a way to organise the working women of Paris in their defence of the Commune and to fight against the exploitation of women. The knowledge of strikes and of the Paris labour movement brought to the union by Nathalie Lemel had a huge influence.

The Women’s Union fought for equal salaries, women’s right to organise her own work, her right to vote and citizenship based on civic and legal equality. It was the foundation for the feminist movements of the 20th century and is at the very roots of modern feminism.

Does France still need Feminism?

French feminist movements continued after the suffragettes, through the radical 70’s and into the present day – some of these are ‘Osez le feminisme’ and ‘Ni Putes ni Soumises’.

Carla Bruni’s recent claim “my generation doesn’t need feminism” created an uproar on social media and led to a huge twitter reaction, with the hastag #dearcarlaburni followed by sentences like “we need feminism because people always assume I’m the secretary”.

On the contrary, stories of French women experiencing abuse in Paris metro while onlookers did nothing but highlight the controversy behind Bruni’s statement. And of course, inequality of salaries is something that remains to be changed. As the French Government’s Minister for the Rights of Women Najat Vallaud-Belkacem declared: “If we accept that men are paid more than women, then we will accept all kinds of inequalities.”

Where do you stand? Does France (and the rest of the world) still need feminism? Share your thoughts in the comments box below.

Image credits:

1. French suffragettes, via back.ac-rennes.fr.

2. First page of Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen, via Wikipedia.

3. Union francaise pour le suffrage des femmes 1909 poster, via Wikipedia Commons.

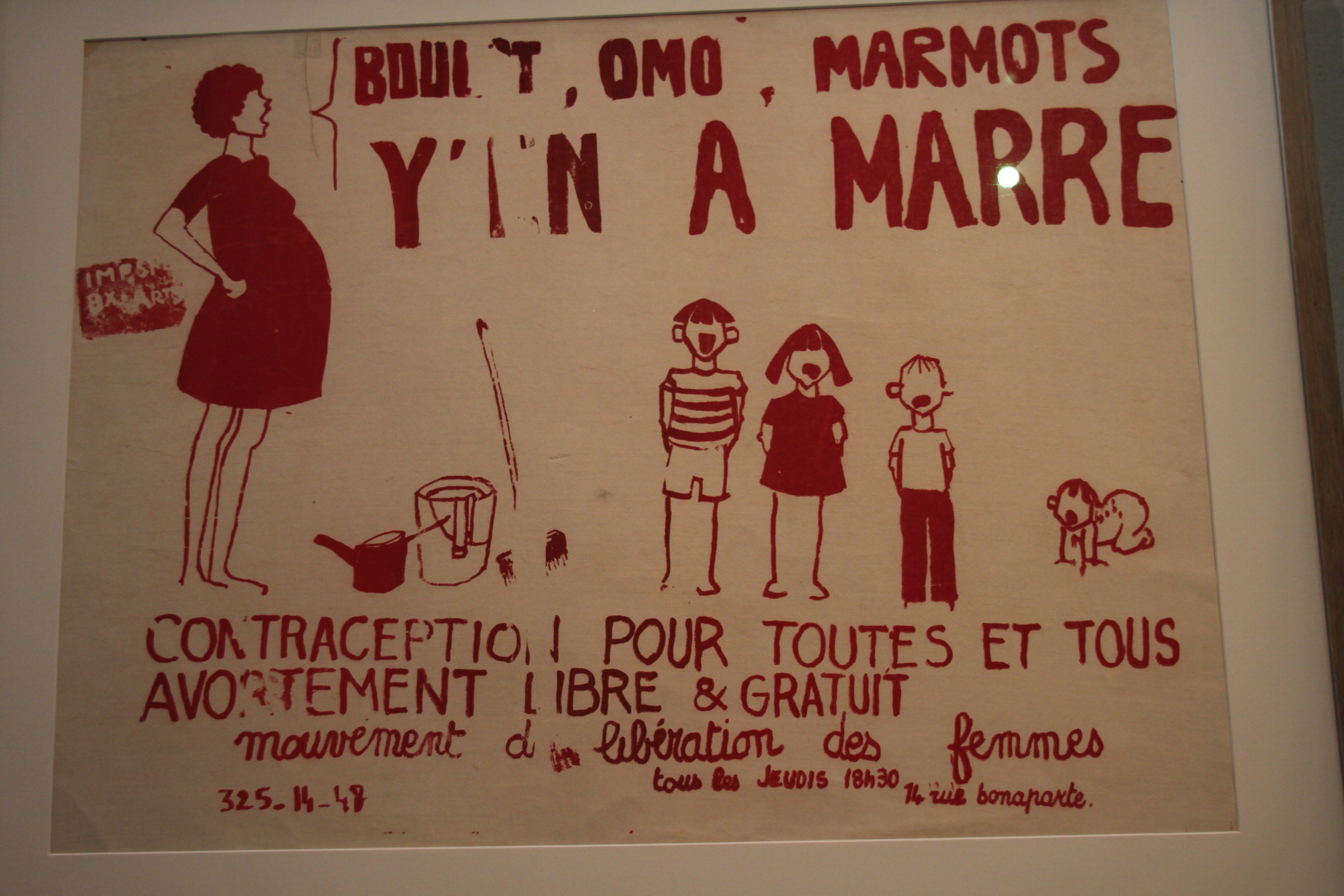

4. Boulot, OMO, Marmots Y’EN A Marre, via Flickr.

5. Najat Vallaud-Belkacem, Fête de la Fraternité à Montpellier, via Flickr.

A great article thank you Stephanie. I didn’t realise France had such a long history of female activism! Good to see that it is continuing today, particularly through social media channels.

Thanks for commenting, Ellen. I’m so glad you found the article informative!

Amazing article, very interesting and insightful. Only thing is in the fourth paragraph, I believe you mean the French Constitution of 1771, not 1971 if I’m not mistaken.

Thanks for pointing out that error, Jose. I’m so glad you enjoyed the article, it was fascinating to research and write!

Oh thank you very much Jose for pointing out our typographical error. So glad that you enjoyed Stephanie’s article.