Looking through the windows: how to read a French gothic cathedral – Part 4

Just a few steps after you first enter the gothic cathedral at Chartres, you may find yourself standing on a curious black and white stone formation. This is the labyrinth, inlaid into the nave floor in the early 13th century. But what is the meaning behind it?

Just a few steps after you first enter the gothic cathedral at Chartres, you may find yourself standing on a curious black and white stone formation. This is the labyrinth, inlaid into the nave floor in the early 13th century. But what is the meaning behind it?

Here we take a closer look at what can be found inside the French gothic cathedral, from labyrinths to stained glass windows, and what these things reveal…

The interior life of French gothic cathedrals

Labyrinths were once a feature of many French gothic cathedrals. One can still be seen at Amiens and we have detailed sketches of the now-destroyed labyrinth at Reims. Scholars still debate their specific meanings, but labyrinths seem to observe a complex spiritual geometry, both in terms of where they are placed within cathedrals and their specific proportions.

At the centre was typically some sort of plaque – the originals at Chartres and Amiens were both unfortunately removed during the French Revolution. Now, the only remnants of the melted-down brass plaque at Chartres are the rivets that once held it in place.

At Amiens, the central medallion celebrated the patrons of the cathedral’s constructions: “in the year of grace 1220, the construction of this church first began. Blessed Evrard was bishop of the diocese at that time. The king of France then was Louis, the son of Philip the Wise. He who directed the work was called Master Robert, surnamed Luzarches. Master Thomas de Cormont came after him, and after him his son Renaud, who had this inscription placed here in the year 1288.”

At Reims, the labyrinth was inlaid with images depicting the four master masons who had charge of the cathedral project; personal and spiritual glory blended together.

Although labyrinths’ original meanings are not clear, some were later used, it seems, as substitutes for those who could not make the pilgrimage to Jerusalem, who sometimes moved around the stone floor on their knees while reciting devotions. Traditionally, authorities at Chartres remove the chairs in this part of the cathedral at midsummer – 21 June – so that modern pilgrims can still walk the 261 metres that lead around the 11 circles. However, this has become so popular that the labyrinth can now be walked far more often, typically Fridays, during the summer months.

French patrons (and saints) of stained glass

French patrons (and saints) of stained glass

Of course, one of the key attractions of French gothic cathedrals is their magnificent stained glass, the structural demands of which consumed so much architectural effort, as we explored in Part Three. Chartres contains some of the best-preserved examples in the world (having been carefully removed during both world wars for safety), which creates the light, bright interior.

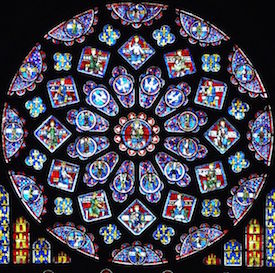

As with so many other features, here too we see spiritual and personal motivations combined. The north rose window, showing the Glorification of the Virgin, was the donation of Blanche of Castile, mother of St Louis. Elements of her coats of arms are visible in the lancet windows just underneath and at the sides of the central rose. These show gold castles on a red background (the symbol of Castile) and gold fleur-de-lys against a blue background, which represented France and was also associated with the Virgin.

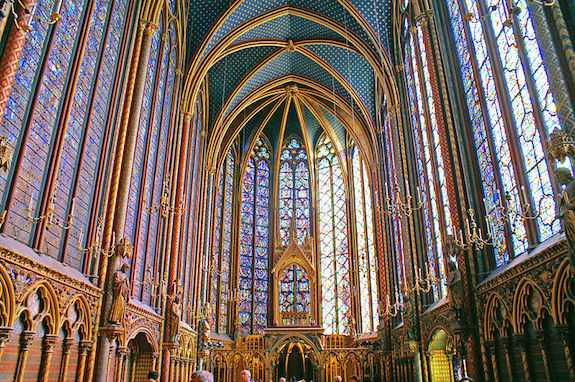

Of course the pièce de resistance is Sainte-Chapelle. In Part One, we looked at why this giant jewel box was built so quickly by Louis IX (St Louis) to house key relics. As a result, the visual program of the upper chapel is completely uniform, and the only donors here were the royal family. The key colours represent them: gold paintwork is complemented by blue for Louis (fleur-de-lys on a blue background), and red for his mother, Blanche of Castile.

Here we see 15 windows separated by pencil-thin columns rising 15 metres high, and containing over 1,000 biblical scenes. These were part of a carefully organised program that depicted the life of Christ from the New Testament and scenes from the Old Testament that focussed particularly on the theme of ‘good rule’ – an appropriate topic of interest for a king and his mother, who had twice been regent of France herself.

Remarkably, two-thirds of the glass we see today is original. Sainte-Chapelle managed to survive the French Revolution relatively intact – at one point serving as a warehouse for flour and later as a deposit for legal archives.

Worldly ambitions and heavenly rewards

Sometimes, gothic cathedrals displayed evidence of patronage that was not merely hinted at through the choice of scenes and colours, but was written clearly into the stained glass. At Amiens, in one window dedicated to the Virgin, we read on the first line:

And on the second:

DED IT M CCL XIX

“Bernard[us] ep[is]c[opus] me dedit MCCLXIX” which translates to “Bernard the bishop gave me 1269.” He’s also depicted kneeling at the feet of the Virgin herself.

Its donor, the bishop Bernard d’Abbeville, was evidently not taking chances when it came to making sure that his donation was acknowledged well beyond his own lifetime!

French gothic cathedrals, in all their different shapes and sizes, not only celebrate the story of the Christian Church in solid stone and technicolour glass, but also reveal the rich and varied stories of the vibrant community life and power of pride of growing medieval towns, and individuals from powerful royal patrons to local guild groups and master masons.

Now that you know some of their secrets, next time you pass by, don’t be afraid to push open the doors to discover a world of human and heavenly tales awaiting inside.

What French gothic cathedrals have you visited? What did you find the most interesting about them? Let us know in the comments below.

Read more on gothic cathedrals…

Part one: discovering secrets

Part two: secrets set in stone

Part three: stories set in stone

Image credits:

1. Labyrinth at Chartres Cathedral, by Maksim, via Wikimedia Commons.

2. Labyrinthe de la Cathédrale de Notre-Dame d’Amiens, by Jean Robert Thibault, via Wikimedia Commons.

3. Cathédrale nd Chartres Vitraux, by Harmonia Amanda, via Wikimedia Commons.

4. Chartres – Vitraile – charron et tonnelier, by MOSSOT, via Wikimedia Commons.

5. Sainte-Chapelle – upper level, by Didier B, via Wikimedia Commons.

6. Stained glass window of Amiens Cathedral, by Alfvanbeem, via Wikimedia Commons.