In search of Rousseau’s ‘noble savage’

In 1789, while French fleets were off in search of the noble savage, the good people of Paris were wandering about, wondering whose head to chop off next.

Anyway, as everyone knows, on 14 July it all came to a head (pun intended). The crowd stormed the Bastille and captured the leader of the garrison. While they were discussing what to do with him, he made a really bad career move – he kicked one of the attackers in the groin. As a result, his head was sawn off by a butcher, fixed on a pike and carried through the streets of the capital.

“C’est une révolte?” asked the King.

“Non sire, ce n’est pas une révolte, c’est une révolution.”

A pivotal moment in French history

In no time at all, Louis XVI himself was being lined up for the chopping block. So was his wife, Marie-Antoinette, because she preferred cake to bread. Or so they say. So her head went into the basket too.

Over 17 000 kilometres away, on the other side of the world, French explorers were blissfully sailing about conducting important geographic and scientific investigations.

Louis had sent them there. Always keen on exploration, he was hoping to find other lands and other civilisations – perhaps because his own people were starting to be so revolting.

Rousseau’s ‘noble savage’ myth takes hold

So, four years prior to the little episode described above, the King of France had appointed Lapérouse (whose full name is far too long to use) as an official explorer. His orders were to lead an expedition around the world.

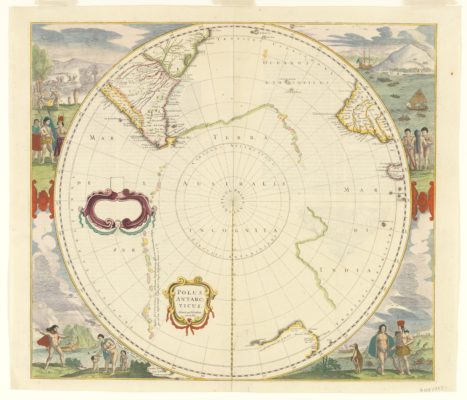

He was directed to complete the Pacific discoveries of James Cook (whom both the King and Lapérouse admired greatly), and correct and complete maps of the South Seas.

If possible, he was to open new sailing routes and enrich French science and scientific collections. This included examining, from an anthropological perspective, what Jean-Jacques Rousseau may have (but probably didn’t) call ‘the noble savage’ – or ‘le bon sauvage‘.

But there was an unfortunate deviation from the script. Lapérouse went AWOL after leaving Sydney Cove, and was never seen again.

“Is there any news of Lapérouse?” the King apparently asked as he climbed to the scaffold, moments before he lost his head. Anyway, once things had settled down again in France and the guillotine was put in mothballs, other explorers went looking for Lapérouse.

Meeting the (very friendly) natives

François Péron was one of them. As a member of the Société des observateurs de l’homme, he wrote a great deal about the Tasmanian Aborigines of the D’Entrecasteaux Channel.

Here’s a report from the voyage of 1800 –1803:

The natives wanted to examine the calves of our legs and our chests, and so far as these were concerned, we allowed them to do everything they wished, oft repeated cries expressing the surprise which the whiteness of our skin seemed to arouse in them. But soon they wished to carry their researches further … they showed an extreme desire to examine our genital organs … Citizen Michel, whom I begged to submit to their entreaties, suddenly exhibited such striking proof of his virility that they all uttered loud cries of surprise mingled with loud roars of laughter which were repeated again and again.

Oh dear, oh dear! Whatever happened to the good old days? Those happy times when heroic and intrepid European explorers landed on tropical shores, meeting, for the first time, les bons sauvages. When, despite both sides being armed to the teeth (albeit muskets and swords versus spears and stones) all they wanted to do was compare the length of each other’s willies, before going on to trade a little black book (and other useless trinkets) for huge tracts of land all over the world.

I wonder who got the better deal?

Are you interested in French history? Had you heard of the concept of the noble savage? Share your knowledge with us in the comments!

Image Credits:

1. ‘Aboriginal Canoes’ (c.1855) by John Thomas Baines, via Wikimedia Commons

2. ‘Execution of Louis XVI’ (1793) by Georg Heinrich Sieveking, via Wikimedia Commons

3. ‘Polus Antarticus Terra Australis Incognita’ (1639) by Hendrik Hondius, via Wikimedia Commons

4. ‘Group of Natives of Tasmania’ (1859) by Robert Dowling, via Wikimedia Commons